It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

9

share:

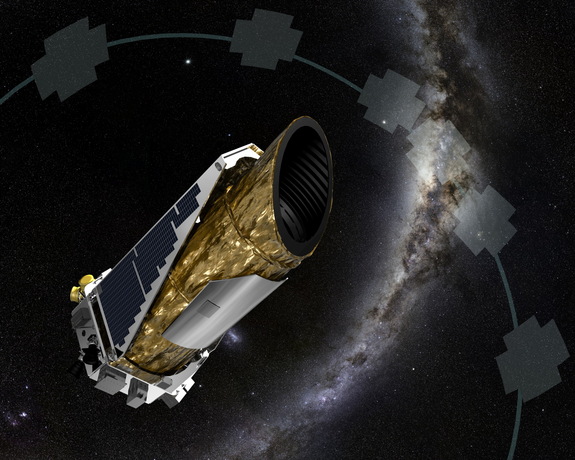

Wonder why there are so many new announcements of extrasolar planets? NASA's Kepler mission has been responsible for many of them. In fact new discoveries are still being made from data Kepler already collected before the loss of it's pointing ability.

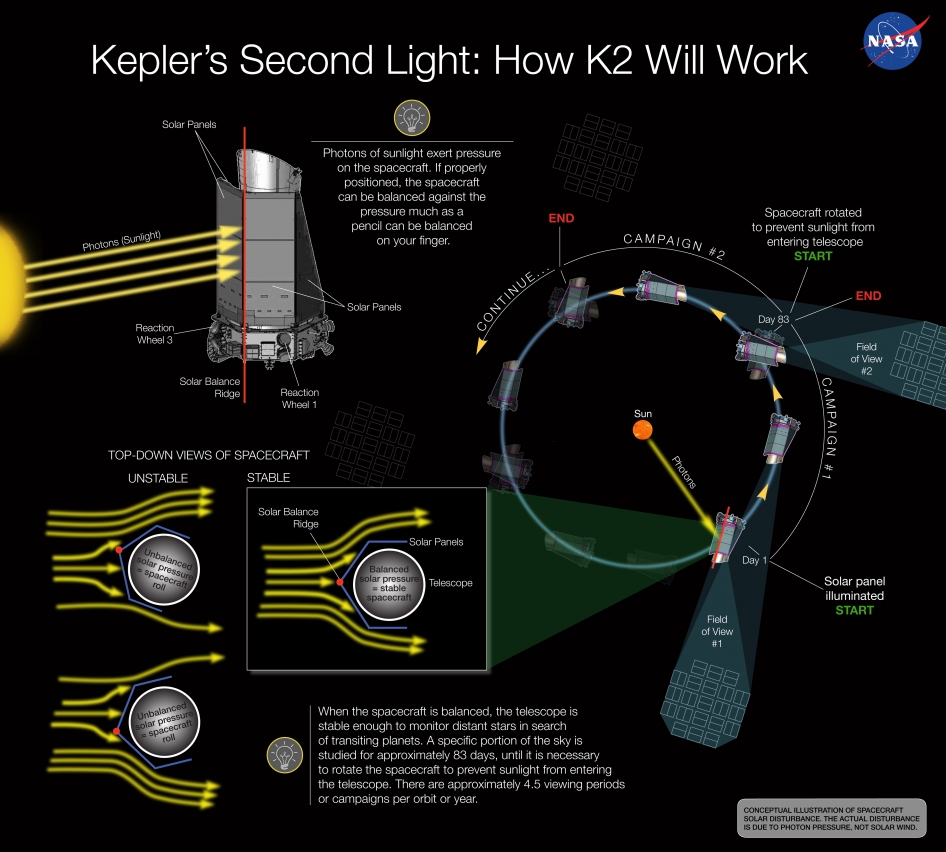

And now, even though the spacecraft was hobbled with the loss of control due to broken reaction wheels, some clever people have figured out how to balance Kepler on our Suns own solar wind using Kepler's solar panel as a bit of a sail!

That's Apollo 13 level ingenuity!

This has enabled an entirely new planet hunting and astrophysics mission called K2.

As I mentioned here earlier this year, approval for a new mission for the beleaguered Kepler spacecraft has been approved!

Universe Today:Kepler Space Telescope Gets A New Exoplanet-Hunting Mission

After several months with their telescope on the sidelines, the Kepler space telescope team has happy news to report: the exoplanet hunter is going to do a new mission that will compensate for the failure that stopped its original work.

Kepler’s exoplanet days were halted last year when the second of its four reaction wheels (pointing devices) failed, which meant the telescope could not gaze at its “field” of stars in the Cygnus constellation for signs of exoplanets transiting their stars.

Results of a NASA Senior Review today, however, showed that the telescope will receive the funding for the K2 mission, which allows for some exoplanet hunting, among other tasks. The telescope will essentially change positions several times a year to do its new mission, which is funded through 2016.

“The approval provides two years of funding for the K2 mission to continue exoplanet discovery, and introduces new scientific observation opportunities to observe notable star clusters, young and old stars, active galaxies and supernovae,” wrote Charlie Sobeck, the mission manager for Kepler, in a mission update today (May 16).

“The team is currently finishing up an end-to-end shakedown of this approach with a full-length campaign (Campaign 0), and is preparing for Campaign 1, the first K2 science observation run, scheduled to begin May 30.”

More at the link I posted above the story.

My professor actually submitted targets for the K2 mission.

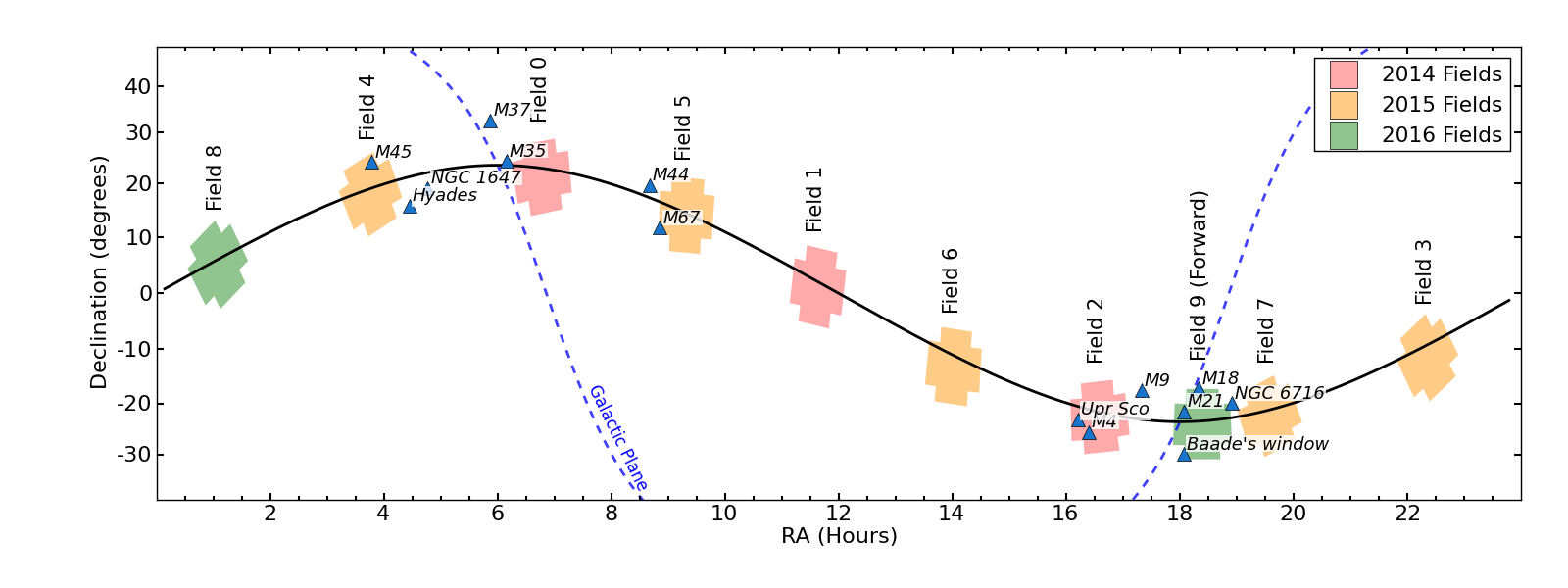

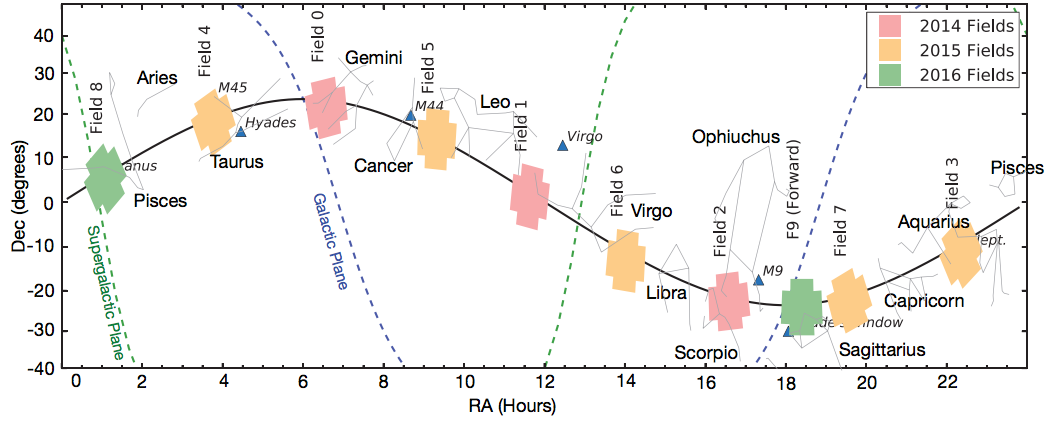

Here's where K2's field of views will be over the next couple of years.

The good news is there are quite a few NEARBY stars in those fields

BTW: You can join in the search for planets with Kepler yourself. Watch the video below:

edit on 16-5-2014 by JadeStar because: (no reason given)

May I ask why they don't just go up and replace the pointing wheels? I would think they would build this thing with breakages in mind.

Oh, wait. I forgot we have no way of getting back up into space ATM. FML.

Space x has that thing, but its not ready yet, correct?

Oh, wait. I forgot we have no way of getting back up into space ATM. FML.

Space x has that thing, but its not ready yet, correct?

a reply to: MarsIsRed

I would like to thank you for your scholarly answer. I am well aware my question could have been laughed at by many, and answered hatefully.

After thinking about your answer for a moment, this makes a lot more sense . Positioning it in orbit around the sun probably protects the sensors from ever pointing directly at the sun, and therefore ruining some of the optics.

Thanks again, and op, thanks for the post.

I would like to thank you for your scholarly answer. I am well aware my question could have been laughed at by many, and answered hatefully.

After thinking about your answer for a moment, this makes a lot more sense . Positioning it in orbit around the sun probably protects the sensors from ever pointing directly at the sun, and therefore ruining some of the optics.

Thanks again, and op, thanks for the post.

a reply to: andr3w68

Even if it was in Earth orbit, it would be far cheaper to get funding to operate the crippled telescope 2 more years than the far more expensive funding to go repair it.

Look at the costs, what was the final cost of the Kepler telescope, maybe $600 million?

And the cost of a shuttle launch is maybe $600 million? (more with R^D factored in).

A Saturn V type launch can handle 5 times the payload and might be capable of launching a crew repair module to the telescope, but the launch vehicle itself would cost over 1.2 billion to launch, plus you'd been a new crew module to put on top which would probably cost several hundred million for the module and more for R&D to you're looking at at least $2 billion to repair a telescope which only cost a fraction of that. So even if we had a Saturn V type launch vehicle, and the capability to do the repair, it doesn't seem economical, when for a smaller amount you could just launch a brand new telescope.

Here's an interesting discussion about launch costs:

forum.nasaspaceflight.com...

Back to the OP topic, yes that's Apollo 13 cleverness, using photon pressure to steer the telescope, very ingenious! I'm glad they can get more useful data from the telescope.

Even if it was in Earth orbit, it would be far cheaper to get funding to operate the crippled telescope 2 more years than the far more expensive funding to go repair it.

Look at the costs, what was the final cost of the Kepler telescope, maybe $600 million?

And the cost of a shuttle launch is maybe $600 million? (more with R^D factored in).

A Saturn V type launch can handle 5 times the payload and might be capable of launching a crew repair module to the telescope, but the launch vehicle itself would cost over 1.2 billion to launch, plus you'd been a new crew module to put on top which would probably cost several hundred million for the module and more for R&D to you're looking at at least $2 billion to repair a telescope which only cost a fraction of that. So even if we had a Saturn V type launch vehicle, and the capability to do the repair, it doesn't seem economical, when for a smaller amount you could just launch a brand new telescope.

Here's an interesting discussion about launch costs:

forum.nasaspaceflight.com...

Back to the OP topic, yes that's Apollo 13 cleverness, using photon pressure to steer the telescope, very ingenious! I'm glad they can get more useful data from the telescope.

There appear to be two stars in the K2 field 1, within 40 light years of Earth. 1.) Ross 128, 10.89 light years distant. Ross 128 is a red dwarf

star (M4 V). 2.) Beta Virginis, also known as Zavijah, 35.65 light years distant. Beta Virginis is classed as F9 V, making it a bit larger and

intrinsically brighter than our Sun.

originally posted by: Ross 54

There appear to be two stars in the K2 field 1, within 40 light years of Earth. 1.) Ross 128, 10.89 light years distant. Ross 128 is a red dwarf star (M4 V). 2.) Beta Virginis, also known as Zavijah, 35.65 light years distant. Beta Virginis is classed as F9 V, making it a bit larger and intrinsically brighter than our Sun.

Yep. And there are other nearby stars in some of the fields.

May I ask what you're using to gather this information?

I was thinking of running a script on SIMBAD but it seems the distance parameter/filter there is messed up. (ie: kiloparsecs popping up as parsecs)

For stars within ~ 16 light years I used wikipedia:

en.wikipedia.org...

For the rest, I used the following rendering of data from the Hipparcos Catalog:

www.astrostudio.org...

en.wikipedia.org...

For the rest, I used the following rendering of data from the Hipparcos Catalog:

www.astrostudio.org...

edit on 17-5-2014 by Ross 54 because: corrected link address

edit on

17-5-2014 by Ross 54 because: corrected link address

edit on 17-5-2014 by Ross 54 because: corrected link

address

edit on 17-5-2014 by Ross 54 because: corrected link address

originally posted by: Arbitrageur

a reply to: andr3w68

Even if it was in Earth orbit, it would be far cheaper to get funding to operate the crippled telescope 2 more years than the far more expensive funding to go repair it.

Look at the costs, what was the final cost of the Kepler telescope, maybe $600 million?

And the cost of a shuttle launch is maybe $600 million? (more with R^D factored in).

A Saturn V type launch can handle 5 times the payload and might be capable of launching a crew repair module to the telescope, but the launch vehicle itself would cost over 1.2 billion to launch, plus you'd been a new crew module to put on top which would probably cost several hundred million for the module and more for R&D to you're looking at at least $2 billion to repair a telescope which only cost a fraction of that. So even if we had a Saturn V type launch vehicle, and the capability to do the repair, it doesn't seem economical, when for a smaller amount you could just launch a brand new telescope.

Here's an interesting discussion about launch costs:

forum.nasaspaceflight.com...

Back to the OP topic, yes that's Apollo 13 cleverness, using photon pressure to steer the telescope, very ingenious! I'm glad they can get more useful data from the telescope.

It would be easier to send up a space tug and have it go pull it to the ISS for repair. After that the tug could refuel and return it to its orbit. Not sure why they have not built space tugs yet. Even an Ion drive though slow could bring stuff back to the ISS for repair.

originally posted by: Ross 54

For stars within ~ 16 light years I used wikipedia:

en.wikipedia.org...

For the rest, I used the following rendering of data from the Hipparcos Catalog:

www.astrostudio.org...

Well done.

edit on 17-5-2014 by JadeStar because: (no reason given)

originally posted by: Xeven

It would be easier to send up a space tug and have it go pull it to the ISS for repair. After that the tug could refuel and return it to its orbit. Not sure why they have not built space tugs yet. Even an Ion drive though slow could bring stuff back to the ISS for repair.

Even if we had a space tug (we don't), Kepler was never designed to be repaired in orbit.

Maybe future planetary spacecraft will have built in solar sails just incase things go tits up. S and f

originally posted by: symptomoftheuniverse

Maybe future planetary spacecraft will have built in solar sails just incase things go tits up. S and f

Nice idea. I'd love that but each addition onto a spacecraft costs money. The larger the item, the more money usually.

That same money could be put into longer lasting/more reliable reaction wheels.

I am bumping this old post because the Kepler's new K2 mission has bagged it's first planet:

From this article on Space.com:

From this article on Space.com:

NASA's Kepler space telescope is discovering alien planets again.

The prolific spacecraft has spotted its first new alien planet since being hobbled by a malfunction in May 2013, researchers announced today (Dec. 18). The newly discovered world, called HIP 116454b, is a "super Earth" about 2.5 times larger than our home planet. It lies 180 light-years from Earth, in the constellation Pisces — close enough to be studied by other instruments, scientists said.

"Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, Kepler has been reborn and is continuing to make discoveries," study lead author Andrew Vanderburg, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement. "Even better, the planet it found is ripe for follow-up studies."

Kepler launched in March 2009, on a 3.5-year mission to determine how frequently Earth-like planets occur around the Milky Way galaxy. The spacecraft has been incredibly successful to date, finding nearly 1,000 confirmed planets — more than half of all known alien worlds — along with about 3,200 other "candidates," the vast majority of which should turn out to be the real deal.

The spacecraft finds planets by the "transit method," watching for the telltale dimming caused when a world cross the face of, or transits, its parent star from Kepler's perspective. Such work requires incredibly precise pointing — an ability the spacecraft lost in May 2013, when the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed.

But the Kepler team didn't give up on the spacecraft. They devised a way to increase Kepler's stability by using the subtle pressure of sunlight, then proposed a new mission called K2, which would continue Kepler's exoplanet hunt in a limited fashion and also study other cosmic objects and phenomena, such as active galaxies and supernova explosions.

originally posted by: Ross 54

For stars within ~ 16 light years I used wikipedia:

en.wikipedia.org...

For the rest, I used the following rendering of data from the Hipparcos Catalog:

www.astrostudio.org...

One interesting thing to note is as one goes further out from SOL there're more and more stellar neighbors because the "bubble" expands its surface area exponentially, thus probabilistically encountering more neighbors as it grows. My math is not good, but thanks to google I can (maybe) get this across. According to google, the surface area of a sphere is 4πr^2. This means the area for a sphere with a 2 light-year diameter is 12.566. If you double the diameter of the sphere the surface area does not double as well, it instead grows exponentially to reach 50.265 ly. Another doubling so that its diameter is 8 ly results with a surface area of 201.062 ly. If you examine the list of the 500 closest stars, it does seem to match the expectation of an exponential growth in the number of neihbors:

Stars within 8 ly: 4

Stars within 16 ly: 35 (4 + 31)

Stars within 32 ly: 132 (4 + 31 + 97)

I wonder what the average density of stars is per volume of given (nearby) interstellar space? I imagine they cluster, so any averaging is loose. I also know there'r galaxies which're denser than others.

edit on 18-12-2014 by jonnywhite because: (no reason given)

originally posted by: jonnywhite

originally posted by: Ross 54

For stars within ~ 16 light years I used wikipedia:

en.wikipedia.org...

For the rest, I used the following rendering of data from the Hipparcos Catalog:

www.astrostudio.org...

One interesting thing to note is as one goes further out from SOL there're more and more stellar neighbors because the "bubble" expands its surface area exponentially, thus probabilistically encountering more neighbors as it grows. My math is not good, but thanks to google I can (maybe) get this across. According to google, the surface area of a sphere is 4πr^2. This means the area for a sphere with a 2 light-year diameter is 12.566. If you double the diameter of the sphere the surface area does not double as well, it instead grows exponentially to reach 50.265 ly. Another doubling so that its diameter is 8 ly results with a surface area of 201.062 ly. If you examine the list of the 500 closest stars, it does seem to match the expectation of an exponential growth in the number of neihbors:

Stars within 8 ly: 4

Stars within 16 ly: 35 (4 + 31)

Stars within 32 ly: 132 (4 + 31 + 97)

Good work and not too far off either for the estimates closer to home but your methodology breaks down as you get further out. Don't let that discourage you though, I love when anyone on ATS uses math to extrapolate stuff like this given a data set.

I wonder what the average density of stars is per volume of given (nearby) interstellar space?

Number = density * volume

In our neck of the woods the average density is around 1 star for every 280 cubic light years.

So this gives us ROUGHLY:

Stars within 8 light years = 33

Stars within 16 light years = 117

Stars within 32 light years = 458

Stars within 64 light years = 3,803

Stars within 128 light years = 30,426

Stars within 256 light years = 243,00

Stars within 512 light years = 1,947,273

Stars within 1,024 light years = 15,578,187

These estimates vary from our catalogs which means that in some cases as much as half the stars remain undiscovered as they are small, dim, low mass M stars aka red dwarfs.

Roughly 1/4 to 1/2 if those stars in each distance category are thought to host an Earthlike planet in the habitable zone of its star.

Assuming that, then the probability of the nearest Earthlike planet being around 12 light years away is around 99.9%

So it's quite likely we have quite a few neighboring earths within 32 light years (about 100 as a very conservative number). Other estimates say between 160-190 earths within 32 light years. With an average age of around 6 billion years (or roughly 1.5 billion years older than our Earth) which raises a fascinating possibility: That we'd be babies perhaps surrounded by a room full of nearby adolescent and young adult civilizations.

I imagine they cluster, so any averaging is loose. I also know there'r galaxies which're denser than others.

The density estimate varies across the galaxy of course, the density decreases rapidly in the direction out of the galactic plane whether above it or below it. It also increases a lot as you move along the plane starting roughly around 18,000 light years in the direction of the center of the galaxy when the density is the highest (around 1,000 stars per cubic light year) . It also is substantially higher in globular clusters within the galaxy. It also falls off slightly between spiral arms.

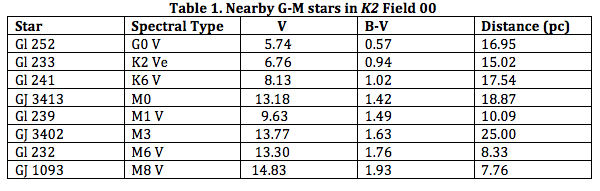

BTW: There are some other nearby stars in the star field this latest discovery was made in.

(pc) = parsec - 1 parsec = 3.26 light years

edit on 19-12-2014 by JadeStar because: (no reason given)

Sometimes it helps to have some perspective so....

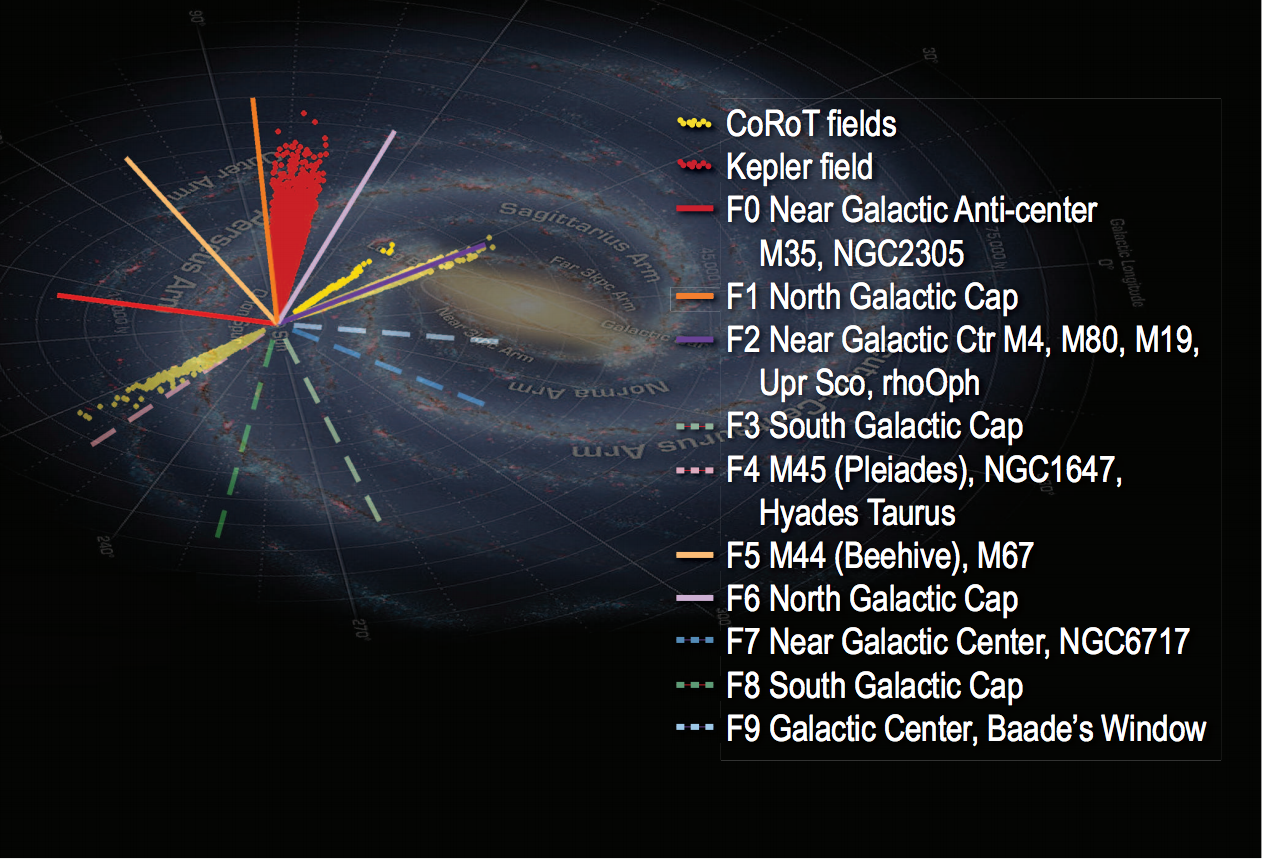

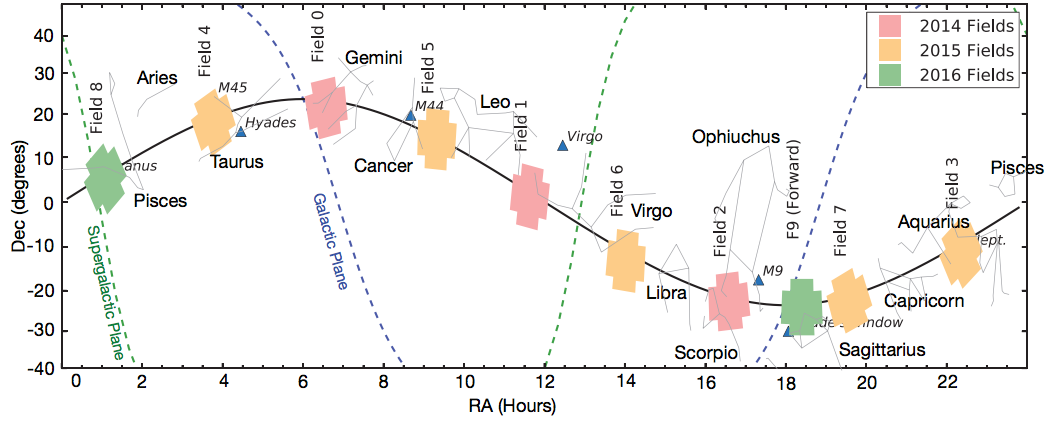

Here is a graphic which shows where K2 will be pointed. The first two items show the planets or planet candidates Kepler and the European Corot missions have already found (represented as red and yellow dots).

The lines below those first two items represent directions of the different fields of stars K2 will look at (Fig.1) color coded so you can see where in the sky from Earth it will be pointed (Fig.2)

Fig.1

Fig.2

Here is a graphic which shows where K2 will be pointed. The first two items show the planets or planet candidates Kepler and the European Corot missions have already found (represented as red and yellow dots).

The lines below those first two items represent directions of the different fields of stars K2 will look at (Fig.1) color coded so you can see where in the sky from Earth it will be pointed (Fig.2)

Fig.1

Fig.2

edit on 20-12-2014 by JadeStar because: (no reason given)

new topics

-

A Warning to America: 25 Ways the US is Being Destroyed

New World Order: 34 minutes ago -

America's Greatest Ally

General Chit Chat: 1 hours ago -

President BIDEN's FBI Raided Donald Trump's Florida Home for OBAMA-NORTH KOREA Documents.

Political Conspiracies: 6 hours ago -

Maestro Benedetto

Literature: 7 hours ago -

Is AI Better Than the Hollywood Elite?

Movies: 8 hours ago -

Las Vegas UFO Spotting Teen Traumatized by Demon Creature in Backyard

Aliens and UFOs: 11 hours ago

top topics

-

President BIDEN's FBI Raided Donald Trump's Florida Home for OBAMA-NORTH KOREA Documents.

Political Conspiracies: 6 hours ago, 27 flags -

Krystalnacht on today's most elite Universities?

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 17 hours ago, 9 flags -

Supreme Court Oral Arguments 4.25.2024 - Are PRESIDENTS IMMUNE From Later Being Prosecuted.

Above Politics: 17 hours ago, 8 flags -

Weinstein's conviction overturned

Mainstream News: 16 hours ago, 8 flags -

Gaza Terrorists Attack US Humanitarian Pier During Construction

Middle East Issues: 12 hours ago, 8 flags -

Massachusetts Drag Queen Leads Young Kids in Free Palestine Chant

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 14 hours ago, 7 flags -

Las Vegas UFO Spotting Teen Traumatized by Demon Creature in Backyard

Aliens and UFOs: 11 hours ago, 6 flags -

Meadows, Giuliani Among 11 Indicted in Arizona in Latest 2020 Election Subversion Case

Mainstream News: 14 hours ago, 5 flags -

2024 Pigeon Forge Rod Run - On the Strip (Video made for you)

Automotive Discussion: 12 hours ago, 4 flags -

Is AI Better Than the Hollywood Elite?

Movies: 8 hours ago, 3 flags

active topics

-

Is AI Better Than the Hollywood Elite?

Movies • 17 • : ThePsycheaux -

The best Rice dish i've ever tasted... Kimchi Rice

Food and Cooking • 26 • : lamhaocc -

A Warning to America: 25 Ways the US is Being Destroyed

New World Order • 1 • : 727Sky -

Massachusetts Drag Queen Leads Young Kids in Free Palestine Chant

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 15 • : tarantulabite1 -

America's Greatest Ally

General Chit Chat • 1 • : BingoMcGoof -

How ageing is" immune deficiency"

Medical Issues & Conspiracies • 35 • : annonentity -

HORRIBLE !! Russian Soldier Drinking Own Urine To Survive In Battle

World War Three • 49 • : Freeborn -

Gaza Terrorists Attack US Humanitarian Pier During Construction

Middle East Issues • 30 • : Asher47 -

Electrical tricks for saving money

Education and Media • 8 • : anned1 -

Hate makes for strange bedfellows

US Political Madness • 48 • : Terpene

9