It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

share:

www.beds.ac.uk...

i'm delighted about this, i never believed that it was a made up rubbish book like some others hypothesized!

(and yes i did a search and had a quick look but didn't find anything related to this recent news)

the sound quality isn't great, but the info is still there:

“I hit on the idea of identifying proper names in the text, following historic approaches which successfully deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs and other mystery scripts, and I then used those names to work out part of the script,” explained Professor Bax

i'm delighted about this, i never believed that it was a made up rubbish book like some others hypothesized!

(and yes i did a search and had a quick look but didn't find anything related to this recent news)

the sound quality isn't great, but the info is still there:

edit on 0pm201428America/ChicagoAmerica/Chicago214 by ladyteeny because: (no reason given)

That seems like a rather obvious solution...

I mean, when I read up on this, I assumed such methods had been tried.

I mean, when I read up on this, I assumed such methods had been tried.

edit on 20-2-2014 by benrl because: (no reason given)

reply to post by ladyteeny

He's not even sure...

How can he know it spells "KANTAIRON"? The alphabet of the code is unknown. I could very well be spelling a name, like ROSY-O'LEAS.

At least that is obvious.

I have a copy of the manuscript. The NSA has a copy of the manuscript. Bax is far from having cracked it.

seven stars which seem to be the Pleiades

He's not even sure...

and also the word KANTAIRON alongside a picture of the plant Centaury

How can he know it spells "KANTAIRON"? The alphabet of the code is unknown. I could very well be spelling a name, like ROSY-O'LEAS.

Although Professor Bax’s decoding is still only partial

At least that is obvious.

I have a copy of the manuscript. The NSA has a copy of the manuscript. Bax is far from having cracked it.

edit on 20-2-2014 by swanne because: (no reason given)

Considering the manuscript contained many pictures of plants I thought that perhaps a linguist and plant biologist would have joined disciplines in

the future to decipher this, however this fellow is one smart linguist in his approach.

reply to post by swanne

There's a possibility a lot of people probably haven't thought about...that the NSA, and other powerful agencies and institutions, HAVE already decoded the manuscript..but didn't like what it had to say.

Or rather didn't like the idea of the public knowing what it had to say for one reason or another.

It wouldn't be the first time documentation is deliberately withheld from public scrutiny, especially if the content is thought to be possibly destabilising to the establishment in some way or another.

I'd be interested to see how far the Prof. gets with his translation...even if it is ultimately only 20% correct, it'll be 20% more than we have as of now.

There's a possibility a lot of people probably haven't thought about...that the NSA, and other powerful agencies and institutions, HAVE already decoded the manuscript..but didn't like what it had to say.

Or rather didn't like the idea of the public knowing what it had to say for one reason or another.

It wouldn't be the first time documentation is deliberately withheld from public scrutiny, especially if the content is thought to be possibly destabilising to the establishment in some way or another.

I'd be interested to see how far the Prof. gets with his translation...even if it is ultimately only 20% correct, it'll be 20% more than we have as of now.

reply to post by ladyteeny

He got my attention when he mentioned that word we are not allowed to discuss on this site lol ...no not Juniper :>)

A good vid to consider on the subject .It's not my cup of tea but I am sure there will be some that will devour this stuff .He does seem to take a simple approach that could work ..Sounds like some document made by Jesuits in trying to make a compilation of a different language .Who knows it could have been the Visigoths or some other tribe that was genocided in earlier times .S&F for you good member ...peace

He got my attention when he mentioned that word we are not allowed to discuss on this site lol ...no not Juniper :>)

A good vid to consider on the subject .It's not my cup of tea but I am sure there will be some that will devour this stuff .He does seem to take a simple approach that could work ..Sounds like some document made by Jesuits in trying to make a compilation of a different language .Who knows it could have been the Visigoths or some other tribe that was genocided in earlier times .S&F for you good member ...peace

Not sure if he's decoding it correctly, hopefully someone can really decode it... I really hate mystery books...

Like the Chinese Classics of Mountain and Sea...

Like the Chinese Classics of Mountain and Sea...

Seems the ideas are intensely researched....id say he may just be on the track....

Long way to go though........

Long way to go though........

reply to post by MysterX

The NSA is not the only organization expert in cryptography. I doubt this conspiracy would be capable of covering ALL organizations, including all those not from the government. I find it more likely that we really don't know.

The copy I have is resistant to anything from caesar squares to frequency analysis. I did found repetitive encrypted words, though. Like our english words "the" or "a", all language have repetitive words - and the Voynich seems to follow that tradition. Which at least rules out skipping letters codes.

The NSA is not the only organization expert in cryptography. I doubt this conspiracy would be capable of covering ALL organizations, including all those not from the government. I find it more likely that we really don't know.

The copy I have is resistant to anything from caesar squares to frequency analysis. I did found repetitive encrypted words, though. Like our english words "the" or "a", all language have repetitive words - and the Voynich seems to follow that tradition. Which at least rules out skipping letters codes.

reply to post by swanne

Perhaps.

This is all speculation of course, but ALL of these other crypto capable organisations would have had to concurrently or previously made a correct translation in order to be in on a cover-up..that is doubtful, considering how long this document has remained undeciphered for.

Only mentioned the NSA specifically (and no doubt 'some' other powerful institutions) as they have the required personnel and equipment necessary to properly crack something like this.

My guess is, if the NSA (and several others) really wanted to crack the manuscript, with their resources, they could and probably already would have done.

Other's, such as the prof in this thread don't have the NSAs resources, or anything like it...but sometimes people get lucky if they are taking the right approach and look at a problem from a different angle. I hope the prof is taking the right approach.

My own gut instinct tells me this is a fairly benign document, writted by Germanic or German-French authors (a brotherhood) and is descriptive of ancient, and for the time period, very secretive and guarded and valuable information concerning apothecaries and spicers. (the 'pepperers and spicers' had a tenuous brotherhood / guild)

These traded and aquired their wares in the East, and had extensive dealing with constantinople and the Arabic peoples of the region.

My guess is the language used is a bastardisation and deliberate corruption of greek and latin, written obviously in code. The reason i feel the document was written in the first place, was because of the imminent fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman empire in the mid-15th century, and was a means of saving and preserving, and denying the valuable (and still closely guarded at that time) information regarding apothecary and spices in general.

It seems peculiar to us today, that such lengths would have been sought to protect this seemingly basic herbal and spice related knowledge, but we must remember, at that time, these were the equivalent of big pharma and multi-million £/$ patented drugs knowledge of today.

Perhaps.

This is all speculation of course, but ALL of these other crypto capable organisations would have had to concurrently or previously made a correct translation in order to be in on a cover-up..that is doubtful, considering how long this document has remained undeciphered for.

Only mentioned the NSA specifically (and no doubt 'some' other powerful institutions) as they have the required personnel and equipment necessary to properly crack something like this.

My guess is, if the NSA (and several others) really wanted to crack the manuscript, with their resources, they could and probably already would have done.

Other's, such as the prof in this thread don't have the NSAs resources, or anything like it...but sometimes people get lucky if they are taking the right approach and look at a problem from a different angle. I hope the prof is taking the right approach.

My own gut instinct tells me this is a fairly benign document, writted by Germanic or German-French authors (a brotherhood) and is descriptive of ancient, and for the time period, very secretive and guarded and valuable information concerning apothecaries and spicers. (the 'pepperers and spicers' had a tenuous brotherhood / guild)

These traded and aquired their wares in the East, and had extensive dealing with constantinople and the Arabic peoples of the region.

My guess is the language used is a bastardisation and deliberate corruption of greek and latin, written obviously in code. The reason i feel the document was written in the first place, was because of the imminent fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman empire in the mid-15th century, and was a means of saving and preserving, and denying the valuable (and still closely guarded at that time) information regarding apothecary and spices in general.

It seems peculiar to us today, that such lengths would have been sought to protect this seemingly basic herbal and spice related knowledge, but we must remember, at that time, these were the equivalent of big pharma and multi-million £/$ patented drugs knowledge of today.

edit on 21-2-2014 by MysterX because: added info

reply to post by ladyteeny

Interesting subject but considering that the NSA and GCHQ have had this encrypted manuscript in there possession for sometime and also the ability to brute force just about any modern day cryptology techniques I think we have to consider the possibility that "They" have indeed decrypted the information contained with in said book long ago and just don't want to share!

Interesting subject but considering that the NSA and GCHQ have had this encrypted manuscript in there possession for sometime and also the ability to brute force just about any modern day cryptology techniques I think we have to consider the possibility that "They" have indeed decrypted the information contained with in said book long ago and just don't want to share!

edit on 21-2-2014 by andy06shake because: (no reason

given)

Not buying it.

Look at the book. There were not a lot of people capable of writing something like this back in the day. A book wasn't just a book, it was a work of art. Only certain people could afford them, and only certain people were capable of producing them. Stranger things have happened, but I doubt only ONE book or ONE instance of this language would exist today. The chance that some tiny group of people wrote with this level of obscurity and complexity doesn't = real to me.

I want it to be real. It's fascinating. I want it to be deciphered, proved legit and tell us something crazy. I just don't think that's going to happen. People have been forging ancient documents for a long time in a bid for cash. Viking map of the US? Pretty clear it was fake. There is BIG money in fakes.

edit on 2120140220141 by Domo1 because: (no reason given)

reply to post by ladyteeny

It is Always nice to see an other attempt to decipher this book. The guy seems to have enough background to give it an educated shot. Thanks for the thread..

F&S for sure.

It is Always nice to see an other attempt to decipher this book. The guy seems to have enough background to give it an educated shot. Thanks for the thread..

F&S for sure.

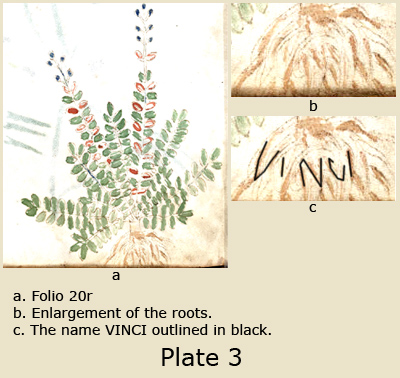

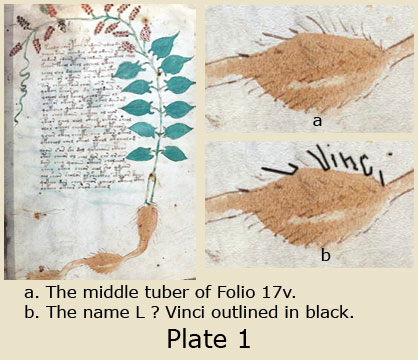

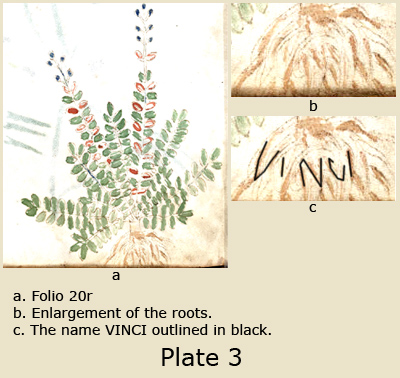

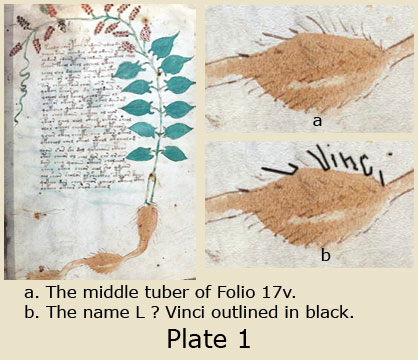

there's a woman out there Edith Sherwood PhD whom I think has the best theory put forth yet. The book wasn't just an elaborate forgery of random

gibberish. It was an extremely early work of Da Vinci and there are clues to that effect all over the folios.

Edith Sherwood Ph.D Cracks Voynich

There's a ton of information on her site and it all looks rather convincing. This is just a very very small portion of what's on her site...

(da vinci marked his other works in the same fashion all the time)

Edith Sherwood Ph.D Cracks Voynich

There's a ton of information on her site and it all looks rather convincing. This is just a very very small portion of what's on her site...

(da vinci marked his other works in the same fashion all the time)

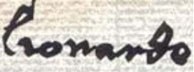

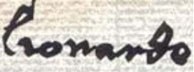

ho was this mysterious individual? Well, his name is written under the sign of the Ram and looks like ob…l, but wait look at that name in the mirror or better still Xerox the picture and look at its reverse in the light and as Figure 2 (the mirror image of figure 1) indicates, the name may be Lionardo. The “r” is added above the name. This tends to support my observation that the writing is similar to that of Leonardo da Vinci who spelt his name Lionardo not Leonardo. Figure 3 - chart signature figure 3 - Leonardo's signature Figure 3 Full Image Figure 3 shows a comparison of this signature, direct and mirror image, with an authentic signature of Leonardo da Vinci, also direct and mirror image.(2) The similarity is apparent but a writing expert would be required to confirm this. In addition there could have been the passage of a number of years between the two signatures, accounting for variations in the letters. The chart signature was written in mirror image writing while the other was not. I also show a drawing of a deer taken from one of Leonardo’s picture puzzles. There is a similarity between this drawing and the ram in the Aries chart.

edit on 21-2-2014 by CallmeRaskolnikov because: (no reason given)

edit on 21-2-2014 by CallmeRaskolnikov because: (no reason

given)

edit on 21-2-2014 by CallmeRaskolnikov because: learning how to embed images

edit on 21-2-2014 by

CallmeRaskolnikov because: (no reason given)

Well, I admire him for tackling this with so much gusto. He has a 'sold out' lecture at his University on Feb. 25th, and now he is planning a

conference entitled 'The Language of the Voynich Manuscript' hoping to attract and receive input from other interested researchers. I wonder if he

sent out special invitations to some of the other researchers from other disciplines to increase attendance and perhaps receive other creative

approaches in translation techniques?

stephenbax.net...

stephenbax.net...

edit on 21-2-2014 by InTheLight because: (no reason given)

reply to post by CallmeRaskolnikov

Was Lionardo, a global Botanist?

In as far as this manuscript not being translated, I think not. I'm no linguists, for sure, but I can see trends and not so obvious trains of thought. There is a organization of some extremely intelligent folks who I'm certain have in fact decoded this manuscript.

The font of the script looks very similar to Hindu, but it isn't. Even though the manuscript was written in the 15 century it seems to even predate ancient Greek, and Sanskrit.

I disagree that this script must come from a civilization that has vanished. There is no evidence to this end. The level of knowledge of plants displayed could be a individual observation but not likely because of the timelines involved and the distances that would have to have been traveled to acquired the information. Most likely it was a group effort over many many years. A well based, knowledgeable society. And in no way of "Cave Man" mentality.

What the manuscript is, is a Medicinal book, for healing. I could be wrong, but some of those plants are just now being recognized for their medicinal values. It appears to me that this book was actually, a gift.

Just because no other specimens of this language have been found to date does not automatically dictate it must come from a extinct society. Ancient Egypt is extinct and no one uses its languages today, but the people survive using another language. To say this society is extinct is not logical because the entirety of the earth has not been explored and registered. We may find we have neighbors who await a reunion of sorts.

Was Lionardo, a global Botanist?

In as far as this manuscript not being translated, I think not. I'm no linguists, for sure, but I can see trends and not so obvious trains of thought. There is a organization of some extremely intelligent folks who I'm certain have in fact decoded this manuscript.

The font of the script looks very similar to Hindu, but it isn't. Even though the manuscript was written in the 15 century it seems to even predate ancient Greek, and Sanskrit.

I disagree that this script must come from a civilization that has vanished. There is no evidence to this end. The level of knowledge of plants displayed could be a individual observation but not likely because of the timelines involved and the distances that would have to have been traveled to acquired the information. Most likely it was a group effort over many many years. A well based, knowledgeable society. And in no way of "Cave Man" mentality.

What the manuscript is, is a Medicinal book, for healing. I could be wrong, but some of those plants are just now being recognized for their medicinal values. It appears to me that this book was actually, a gift.

Just because no other specimens of this language have been found to date does not automatically dictate it must come from a extinct society. Ancient Egypt is extinct and no one uses its languages today, but the people survive using another language. To say this society is extinct is not logical because the entirety of the earth has not been explored and registered. We may find we have neighbors who await a reunion of sorts.

reply to post by All Seeing Eye

global botanist? you do realize that even back in Leonardo's day there were printers who produced printed identifiers for plants and herbs. there existed libraries back then too. if you had read the site at all there is a specific section "the voynich botanical plants" discussing this and providing information that makes it entirely possible that leo could have produced these drawings himself

Voynich Botanical Plants Explained

global botanist? you do realize that even back in Leonardo's day there were printers who produced printed identifiers for plants and herbs. there existed libraries back then too. if you had read the site at all there is a specific section "the voynich botanical plants" discussing this and providing information that makes it entirely possible that leo could have produced these drawings himself

Voynich Botanical Plants Explained

botanists, who examined the VM’s botanical drawings, have dismissed them as a mishmash of flowers and leaves belonging to unrelated plants. The fanciful nature of some drawings makes identification with 21st century plants difficult. For example, one plant has a root system resembling a headless cat, another has leaves that look like a series of spears. The large number and variety of species in the plant kingdom further complicates the problem. The 18th century Linnean Herbarium contains over 14,000 plants classified into genera. The Ranunculus genus had 78 species; today, this number has increased to 600. Other members of the Ranunculaceae family include buttercups, spearworts, water crowfoots, winter aconite, monk’s hood and the lesser celandine. Their flowers may have a few, many or no petals at all and a variety of different types of leaves. The diversity of flowers and leaves within a genus and the magnitude of the plant kingdom, makes the identification of the VM’s botanical plants rather like looking for a needle in a haystack. The botanical section of the VM may represent, in part, a private herbal. Consulting herbals used in the Middle Ages should help with the identification of these drawings. Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 – c. 90 AD) produced the first herbal. His simple, natural drawings, used to illustrate De Materia Medica, were the gold standard for herbal illustrations until about 1550 AD. The illustrations in many subsequent herbals are degraded, stylized reproductions of Dioscorides’ work. Fortunately, by the 15th century, herbal illustrations had improved. These illustrations were simple basic drawings of plants, often representing not much more than a twig with a few leaves and perhaps a few flowers. By the middle of the 16th century, botanists like Dodoens Pemptades, Fuch and Mattioli reintroduced naturalism and more complexity into their herbal drawings. Digitized copies of 15th century herbal books and manuscripts, contemporary with the VM, are now available on the Internet. The simple woodcut illustrations in the herbal incunabula (books printed before 1500 AD) in conjunction with their Latin names, have allowed me to identify many of the VM’s botanical drawings. I also used illustrations from the following two books: Herbs, for the Mediaeval Household, Margaret B. Freeman, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1943. Herbals, their Origin and Evolution, Agnes Arber, Cambridge University Press, 1938. The incunabula were: Herbarius, Peter Schoeffer, 1484, in Latin., MGB Digital Library. Hortus Sanitatis, Peter Schoeffer, 1485, The only illustrations I could find from this herbal are from Margaret Freeman’s book, Herbs, for the Mediaeval Household. Gart der Gesundheit, Peter Schoeffer, 1485, Botanicus.internet site. Ortus Sanitatis, Jacob Meydenbach, Mainz, Germany, 1491. There are two copies of this herbal, one in black and white with easy to read Latin titles is available on the Smithsonian internet site, and a colored version on the Harvard University Library site. Herbarius Patauie Impressus, 1485, Harvard University Library site. Some of the VM’s botanical drawings show a surprising similarity to woodcut illustrations in herbals, printed after 1484, using the Gutenberg Press in Mainz, Germany. One of the printers, Peter Schoeffer, was apprenticed to Gutenberg and after Gutenberg’s death, he continued printing his own books, publishing his first herbal in 1484. His herbals were printed in either German or Latin. It should be pointed out that Peter Schoeffer was just the publisher of these herbals; he probably did not write the texts. Printers of other herbals used many of his woodcuts. The author or authors of these herbals are unknown, likewise the origin of the woodcuts and who carved them. Examining these woodcuts caused me to postulate that many of the VM’s drawings were not drawn from nature, but were copied from a contemporary herbal or herbals with similar odd characteristics. VM folio 14r has leaves like spears and is very similar to the illustration of sorrel, in Peter Schoeffer’s Herbarium, Plate 1. The illustration of diptamus in Jacob Meydenbach’s Ortus Sanitatis has roots resembling a headless animal, similar to the plant, folio 90v1, that has roots like a headless cat, Plate 2. Other examples are given later. Nobody in the 15th century would have considered the VM’s drawings strange or unacceptable; they are no different from other 15th century herbal drawings. Plate 1 Plate 1 Plate 2 Plate 2 What initially puzzled me was why some of the VM’s drawings appear almost identical to illustrations from herbals printed in Germany, from 1484 onwards. The VM is assumed to have originated in Italy sometime around the middle of the 15th century. Further investigation showed that some VM drawings closely resembled illustrations from the following Italian herbals: Herbal, N. Italy (Lombardy), c.1440, Sloane MS 4016, British Library internet site. Tractatus de herbis (Herbal); De Simplici Medicina, Bartholomaei Mini de Senis; Platearius; Nicolaus, between c.1280 and c.1310. S.Italy (Solerno). Egerton MS 747, British Library internet site. This manuscript provides English names with the plant illustrations. Herbarien des Pseudo Apulelus und Antonus Musa, & Essen 305, Fulda. C~1470. The small size of the illustrations made the print too small to read. Pseudo Antonus Musa. De Herba Vettonica Liber. Hartley MS 1585. Produced in the last quarter of the 12th century. British Library internet site. Antonius Musa was a botanist and physician to the Roman Emperor Augustus. His brother was physician to King Juba II of Mauretania (Libya). Further investigation of the drawings of VM’s plants indicated that they could be divided into two basic groups, plants that were drawn directly from nature and those drawings that were very similar to or could be identified from illustrations in German or Italian herbals. Latin names were used to identify plants in the early herbals. If this name later became the botanical name of the plant, identification is simple. However if the two names are different, then correlating an illustration with a living plant is not always possible. Plate 3 Plate 3 Many of the drawings of plants, I have dubbed drawn directly from nature, are alpine. I had the good fortune last year, while on a cruise down the Danube, of buying the following book: Alpen Pflanzen, text R.Slavik, illustrations j. Kaplicka, Artia, Prag, 1977. I realized, while thumbing through its pages, that I was looking at a number of the VM drawings, drawings I was unable to find counterparts for in the various herbals I had consulted. This observation probably indicates that the author of the VM lived in a hilly or mountainous region of Northern Italyedit on 21-2-2014 by CallmeRaskolnikov because: (no reason given)

reply to post by Domo1

So you are not saying the vikings didn't come here right.... Why is history distorted in this country, like Columbus discovered America, what a joke.

The NSA could crack any decode in very short time. They have acres and acres of servers at their disposal. But, they are to busy listening to your phone calls and reading your emails lol.

The Bot

So you are not saying the vikings didn't come here right.... Why is history distorted in this country, like Columbus discovered America, what a joke.

The NSA could crack any decode in very short time. They have acres and acres of servers at their disposal. But, they are to busy listening to your phone calls and reading your emails lol.

The Bot

reply to post by CallmeRaskolnikov

Im not suggesting he might not of had a hand in the creation of the manuscript, its just unlikely one person was the author, similar to Ken

Follett and his crew of researchers.

Nor will I take away from Leo that he was far in advance of his time. He may have been more than what we have been lead to believe. In as far as libraries and printing presses, no doubt they were in existence, but it appears the text in the manuscript was written by hand, what do we have to show the drawings were pressed? They too look to be hand drawn.

Nor will I take away from Leo that he was far in advance of his time. He may have been more than what we have been lead to believe. In as far as libraries and printing presses, no doubt they were in existence, but it appears the text in the manuscript was written by hand, what do we have to show the drawings were pressed? They too look to be hand drawn.

reply to post by All Seeing Eye

I understand what you're trying to say. That woman Edith posits that the botanical stuff included wasn't pressed itself but, that he could have referred to already existing pressings of plants and herbs. On her site she has side by side comparisons of woodcuts that were popular during the period and compares them to specific voynich botanical drawings. So he wouldn't have needed to be a botanical specialist of every plant. A lot of the plants in voynich are also similar to those found where Leo lived in some hilly area of Italy.

I think Leo is one of those rare people that was intelligent enough to accomplish something that's stumped so many people. That site has a ton of great information it's really worth a closer look.

I understand what you're trying to say. That woman Edith posits that the botanical stuff included wasn't pressed itself but, that he could have referred to already existing pressings of plants and herbs. On her site she has side by side comparisons of woodcuts that were popular during the period and compares them to specific voynich botanical drawings. So he wouldn't have needed to be a botanical specialist of every plant. A lot of the plants in voynich are also similar to those found where Leo lived in some hilly area of Italy.

I think Leo is one of those rare people that was intelligent enough to accomplish something that's stumped so many people. That site has a ton of great information it's really worth a closer look.

new topics

-

Drones (QUESTION) TERMINATOR (QUESTION)

General Chit Chat: 1 hours ago -

Canada Banning more Shovels

General Chit Chat: 4 hours ago -

A priest who sexually assaulted a sleeping man on a train has been jailed for 16 months.

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 10 hours ago -

The goal of UFO's/ fallen angels doesn't need to be questioned - It can be discerned

Aliens and UFOs: 10 hours ago

top topics

-

Jan 6th truth is starting to leak out.

US Political Madness: 17 hours ago, 23 flags -

Biden pardons 39 and commutes 1500 sentences…

Mainstream News: 15 hours ago, 8 flags -

Canada Banning more Shovels

General Chit Chat: 4 hours ago, 5 flags -

The goal of UFO's/ fallen angels doesn't need to be questioned - It can be discerned

Aliens and UFOs: 10 hours ago, 4 flags -

A priest who sexually assaulted a sleeping man on a train has been jailed for 16 months.

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 10 hours ago, 2 flags -

Drones (QUESTION) TERMINATOR (QUESTION)

General Chit Chat: 1 hours ago, 0 flags

active topics

-

Drones everywhere in New Jersey

Aliens and UFOs • 94 • : 38181 -

-@TH3WH17ERABB17- -Q- ---TIME TO SHOW THE WORLD--- -Part- --44--

Dissecting Disinformation • 3652 • : fringeofthefringe -

Canada Banning more Shovels

General Chit Chat • 2 • : chiefsmom -

Magic Vaporizing Ray Gun Claim - More Proof You Can't Believe Anything Hamas Says

War On Terrorism • 17 • : andy06shake -

Drones (QUESTION) TERMINATOR (QUESTION)

General Chit Chat • 2 • : BeyondKnowledge3 -

The Acronym Game .. Pt.4

General Chit Chat • 1011 • : JJproductions -

Jan 6th truth is starting to leak out.

US Political Madness • 21 • : network dude -

A priest who sexually assaulted a sleeping man on a train has been jailed for 16 months.

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 10 • : stosh64 -

The goal of UFO's/ fallen angels doesn't need to be questioned - It can be discerned

Aliens and UFOs • 8 • : ARM19688 -

CNNs DON LEMON hints that Zucker's Disgraced Exit May Doom His Black Gay Primetime Anchorship.

Education and Media • 47 • : yeahright