It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

3

share:

I hear this all the time, that the U.S. interest rate set by the Fed is bound to rise eventually and in so doing, it will trigger lenders losing some

$441 trillion in interest rate derivatives contracts. So, it would be catastrophic for interest rates to rise to its historic average of about 2.5%

over the rate of inflation - somewhere over 5%.

Many authoritative economists state with certainty that the interests rate will sooner or later rise (and indeed they are, a little). If that's the case, then catastrophe is inevitable.

Cordiant - Why Interest Rates Will Rise

I have heard rationale such as: interest rates have always rebounded throughout history; or, the Fed is going to taper quantitative easing at some point (they state as much) and in so doing, interest rates will rise. I get that.

But why is it that their hand will be forced? What is the mechanism that forces interest rates to rise in cases of prolonged zero or near-zero interest rates? The link posted above has this to say:

Are there any Austrian economists around willing to explain this to me? I have had it explained a few different times over the years but I can never recall it.

Many authoritative economists state with certainty that the interests rate will sooner or later rise (and indeed they are, a little). If that's the case, then catastrophe is inevitable.

Cordiant - Why Interest Rates Will Rise

I have heard rationale such as: interest rates have always rebounded throughout history; or, the Fed is going to taper quantitative easing at some point (they state as much) and in so doing, interest rates will rise. I get that.

But why is it that their hand will be forced? What is the mechanism that forces interest rates to rise in cases of prolonged zero or near-zero interest rates? The link posted above has this to say:

This coming investment boom will put sustained upward pressure on real interest rates as the demand for capital will exceed the supply of savings.

Are there any Austrian economists around willing to explain this to me? I have had it explained a few different times over the years but I can never recall it.

Inflation is going to happen due to the increase of the US Monetary Base: See Graph: research.stlouisfed.org...

The fact is; the US is trying to print itself out-of-debt; but this historically has proven to end an economy and devalue it. There is a long standing history of how fiat currency fails and the same will apply to the US. For some history: dailyreckoning.com...

Now that you have seen the US MB graph, can you see why inflation is inevitable, even economic collapse?

The fact is; the US is trying to print itself out-of-debt; but this historically has proven to end an economy and devalue it. There is a long standing history of how fiat currency fails and the same will apply to the US. For some history: dailyreckoning.com...

Now that you have seen the US MB graph, can you see why inflation is inevitable, even economic collapse?

reply to post by YouAreDreaming

I understand that much of it. But there is a difference between death by inflation and death by derivatives, as I understand it. My question is, what is it about inflation, that forces interest rates to rise eventually, that will pop the derivatives bubble? I'm going to read through your second link, but I think it addresses a different type of destruction.

I understand that much of it. But there is a difference between death by inflation and death by derivatives, as I understand it. My question is, what is it about inflation, that forces interest rates to rise eventually, that will pop the derivatives bubble? I'm going to read through your second link, but I think it addresses a different type of destruction.

Samtzurr

reply to post by YouAreDreaming

I understand that much of it. But there is a difference between death by inflation and death by derivatives, as I understand it. My question is, what is it about inflation, that forces interest rates to rise eventually, that will pop the derivatives bubble? I'm going to read through your second link, but I think it addresses a different type of destruction.

The monetary base is important because each dollar printed devalues the rest which is directly linked to inflation because the value of the currency is devalued. In 2008, 800 billion dollars existed in the BASE and by 2013 it's now 3.6 Trillion dollars which by itself can decrease the value of the dollar by 78%.

Not to mention the debt and derivative bubble. All of these factor into one massive collapse in the horizon; and we could be at the start of it right now with the Shutdown. This economy is doomed to fail, I don't see any way out short of total collapse at some point.

What starts as mild inflation will balloon into hyperinflation especially if the debt is not paid back; but I think even that is unlikely to fix the derivatives and the over-printing of money. Not sure how long that can bandaid the economy before it's called on.

How that affects interest rates is unknown because the banks control that and can raise or lower it to stimulate the economy I think they know if they raise it it will likely backfire and implode the economy do to how volatile it is right now.

edit on 8-10-2013 by YouAreDreaming because: (no reason given)

reply to post by YouAreDreaming

I still want to know what the rationale is for saying that interest rates are forced to rise. Know what I mean? Yes, the central bank essentially controls interest rates. But according to many economists, they cannot stop the rate from rising. Is it because they are caught in a catch-22? That is, if they don't raise interest rates, the monetary supply will rise to the point of hyperinflation, and if they do, the futures [derivatives] market will fall apart? Or is it for some other reason?

And what is meant by the source above which says, "This coming investment boom will put sustained upward pressure on real interest rates as the demand for capital will exceed the supply of savings"?

I still want to know what the rationale is for saying that interest rates are forced to rise. Know what I mean? Yes, the central bank essentially controls interest rates. But according to many economists, they cannot stop the rate from rising. Is it because they are caught in a catch-22? That is, if they don't raise interest rates, the monetary supply will rise to the point of hyperinflation, and if they do, the futures [derivatives] market will fall apart? Or is it for some other reason?

And what is meant by the source above which says, "This coming investment boom will put sustained upward pressure on real interest rates as the demand for capital will exceed the supply of savings"?

edit on 8-10-2013 by Samtzurr because: (no reason given)

reply to post by Samtzurr

It's not so much that interest rates will rise, in my opinion. It's that interest and inflationary forces will eventually return to their natural state. That actually has a number to it and not the artificially manipulated and depressed level it's been at for a long time now.

When they can't cook the books anymore and the funny money printing to artificially hold down interest rates for our own little utopia of economic indicators comes to an end? We'll be in real terrible trouble almost instantly.

After all...it was many trillions of dollars in debt ago we last saw those forces allowed to operate without massive artificial influence and control attempted. it can't last forever though and they are already almost out of tricks.

It's not so much that interest rates will rise, in my opinion. It's that interest and inflationary forces will eventually return to their natural state. That actually has a number to it and not the artificially manipulated and depressed level it's been at for a long time now.

When they can't cook the books anymore and the funny money printing to artificially hold down interest rates for our own little utopia of economic indicators comes to an end? We'll be in real terrible trouble almost instantly.

After all...it was many trillions of dollars in debt ago we last saw those forces allowed to operate without massive artificial influence and control attempted. it can't last forever though and they are already almost out of tricks.

edit on 8-10-2013 by Wrabbit2000 because: (no reason given)

Is it not possible that the inevitable crash of currency that occurs when nations turn on the printing presses in such a grand scale might be

mitigated by the fact that pretty much every nation has been desperately printing as much money as they possibly can?

So while the dollar has lost a huge chunk of its real value, the pound and the Euro and the Yen have also all lost a huge amount of their value. So it's all relative?

So while the dollar has lost a huge chunk of its real value, the pound and the Euro and the Yen have also all lost a huge amount of their value. So it's all relative?

The financial history of the Wiemar republic makes most interesting reading, five billion Deutchmarks to buy a loaf of bread, or was it five million?

cannot remember, anyway, a barrow full of paper, for a loaf of bread.

reply to post by Painterz

That's just it. 'Nations' haven't been printing money like it's toilet paper. A couple specific nations have been.

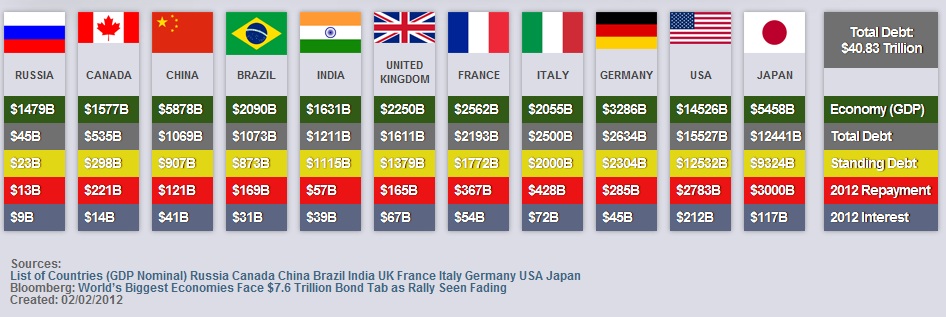

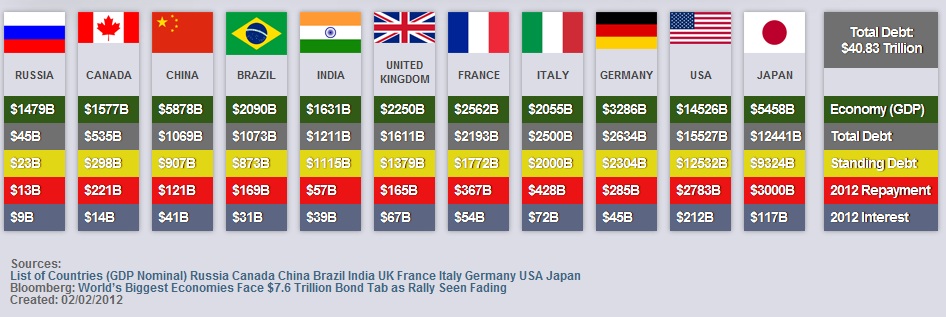

(Source)

This trip into fiscal insanity and economics only a petulant child could consider logical hasn't been a universally accepted thing. Not by any stretch have all nations drank this toxic kool-aid. Most, in fact haven't. If you've watched headlines very closely, Obama has, personally and directly, encouraged the EU and Britain to both embrace more debt and join us in the quantitative easing. Mixed results for getting anyone onboard and again, some?

Some nations have already learned this lesson. The Soviet Union collapsed in large part due to runaway debt the world didn't even know much about until about 1988, as I believe it started coming out. See the debt numbers (a year or so dated) above? Russia learned....while we've embraced debt like an alcoholic embracing the bottle. Right to rock bottom.

That's just it. 'Nations' haven't been printing money like it's toilet paper. A couple specific nations have been.

(Source)

This trip into fiscal insanity and economics only a petulant child could consider logical hasn't been a universally accepted thing. Not by any stretch have all nations drank this toxic kool-aid. Most, in fact haven't. If you've watched headlines very closely, Obama has, personally and directly, encouraged the EU and Britain to both embrace more debt and join us in the quantitative easing. Mixed results for getting anyone onboard and again, some?

Some nations have already learned this lesson. The Soviet Union collapsed in large part due to runaway debt the world didn't even know much about until about 1988, as I believe it started coming out. See the debt numbers (a year or so dated) above? Russia learned....while we've embraced debt like an alcoholic embracing the bottle. Right to rock bottom.

edit on 8-10-2013 by Wrabbit2000 because: (no reason given)

Here's how I understand malinvestment...

In a free market economy, real interest rates would lower as more bonds are bought (because lenders don't have to offer as much incentive when demand is good). Low interest rates simultaneously make long-term loans more attractive, encouraging business to invest in long-term projects, R&D and so forth. They know it will pay off because people are spending less currently and saving more for later.

While this happens, resources are similarly diverted from short-term production to long-term production. Projects are more tailored to the limits of production such as resource extraction, manpower and funding. A beautiful, harmonic trade off between these factors occurs when interest rates reflect real demand and when they make accurate statements about what people are doing with their money.

When a central bank, like the Federal Reserve, is buying $86 billion dollars worth of bonds a month, there is no competition driving up the interest rate; if nobody else will buy the bonds, the Fed will, so why raise interest rates? This #ers up the whole economy. Both short-term and long-term production is occurring and the limited factors of production cannot accommodate both. Many projects go unfinished, such as housing developments in 2007, and then we have periodic busts. Projects finished later don't generate the expected profits because nobody has actually been saving, not to the degree the fixed interest rates suggest. That's called the business cycle and I'm pretty sure I have it straight.

Ludwig on Mises explained it in a metaphor in his generational work, "Human Action." He said, imagine an economy of one man or woman. He said "one man," but that was the 1920s. This man decides to build a house, and with no accurate measure of the availability of resources, he decides to build an arbitrarily large house. The problem is, his plans call for 20% more bricks than he has. He begins building, and the economy of one man looks good, for awhile with full employment, increase in equity, and ideal wealth distribution. Should a third party looking on at this doomed economy and intervene? In the short-term, he's doing well for himself, he has hope. But in a couple of years he will have most of a house that's always flooded. What the Federal Reserve does consistently, is gets him drunk.

So the assumption that interest rates /will rise inevitably/ comes from the imminent realization that there isn't enough capital to support all of the ongoing projects, and more importantly, businesses are failing left and right, so on the supply side there is simply not enough going around (shortages). So maybe first there is over-harvesting of a jungle to provide more timber > which destroys the ecosystem of the lac beetle > shellac harvested from an anal gland in that beetle drops > candy companies like Skittles have to discontinue shiny candy products which makes some of their means of production idle. In this case over-harvesting actually causes waste. There is also price distortion which causes waste in another way, but that's a topic for another post.

Here's the thing. If interest rates rise, which they inevitably will, the interest rate derivatives bubble will pop. It's worth $441 trillion according to the Bank of International Settlements. The larger derivatives market is much larger, around $5 quadrillion worth of derivatives. But just the $441 trillion interest rate derivative market imploding would send ripples through every supply chain in the country and through much of the world. If /just/ lumber production stalls, everything using lumber and everything using paper slows, and much of it fails. But every resource and level of production is effected by every other one and every stutter in the supply chain compounds into other industries.

In a free market economy, real interest rates would lower as more bonds are bought (because lenders don't have to offer as much incentive when demand is good). Low interest rates simultaneously make long-term loans more attractive, encouraging business to invest in long-term projects, R&D and so forth. They know it will pay off because people are spending less currently and saving more for later.

While this happens, resources are similarly diverted from short-term production to long-term production. Projects are more tailored to the limits of production such as resource extraction, manpower and funding. A beautiful, harmonic trade off between these factors occurs when interest rates reflect real demand and when they make accurate statements about what people are doing with their money.

When a central bank, like the Federal Reserve, is buying $86 billion dollars worth of bonds a month, there is no competition driving up the interest rate; if nobody else will buy the bonds, the Fed will, so why raise interest rates? This #ers up the whole economy. Both short-term and long-term production is occurring and the limited factors of production cannot accommodate both. Many projects go unfinished, such as housing developments in 2007, and then we have periodic busts. Projects finished later don't generate the expected profits because nobody has actually been saving, not to the degree the fixed interest rates suggest. That's called the business cycle and I'm pretty sure I have it straight.

Ludwig on Mises explained it in a metaphor in his generational work, "Human Action." He said, imagine an economy of one man or woman. He said "one man," but that was the 1920s. This man decides to build a house, and with no accurate measure of the availability of resources, he decides to build an arbitrarily large house. The problem is, his plans call for 20% more bricks than he has. He begins building, and the economy of one man looks good, for awhile with full employment, increase in equity, and ideal wealth distribution. Should a third party looking on at this doomed economy and intervene? In the short-term, he's doing well for himself, he has hope. But in a couple of years he will have most of a house that's always flooded. What the Federal Reserve does consistently, is gets him drunk.

So the assumption that interest rates /will rise inevitably/ comes from the imminent realization that there isn't enough capital to support all of the ongoing projects, and more importantly, businesses are failing left and right, so on the supply side there is simply not enough going around (shortages). So maybe first there is over-harvesting of a jungle to provide more timber > which destroys the ecosystem of the lac beetle > shellac harvested from an anal gland in that beetle drops > candy companies like Skittles have to discontinue shiny candy products which makes some of their means of production idle. In this case over-harvesting actually causes waste. There is also price distortion which causes waste in another way, but that's a topic for another post.

Here's the thing. If interest rates rise, which they inevitably will, the interest rate derivatives bubble will pop. It's worth $441 trillion according to the Bank of International Settlements. The larger derivatives market is much larger, around $5 quadrillion worth of derivatives. But just the $441 trillion interest rate derivative market imploding would send ripples through every supply chain in the country and through much of the world. If /just/ lumber production stalls, everything using lumber and everything using paper slows, and much of it fails. But every resource and level of production is effected by every other one and every stutter in the supply chain compounds into other industries.

reply to post by Wrabbit2000

You're right about that! By 2016, the U.S. will pay more to service debt interest than Russia will for its entire federal budget. And by 2020, the U.S. will be paying more than double for debt interest than it will in 2016.

Russia's doing a better job of it. They're /cutting/ spending to stimulate growth. They're supplementing their budget, as well, out of their sovereign wealth fund, which they responsibly put money into every year mostly from profit on energy exports. Can you imagine having a government that /saved/ money for times like this? Rather than debating annually or bi-annually whether to raise the debt ceiling (Russia doesn't have one, in fact only the U.S. and Denmark do, and Denmark revises theirs every year with their budget), what if our government just drew from its savings?

You're right about that! By 2016, the U.S. will pay more to service debt interest than Russia will for its entire federal budget. And by 2020, the U.S. will be paying more than double for debt interest than it will in 2016.

Russia's doing a better job of it. They're /cutting/ spending to stimulate growth. They're supplementing their budget, as well, out of their sovereign wealth fund, which they responsibly put money into every year mostly from profit on energy exports. Can you imagine having a government that /saved/ money for times like this? Rather than debating annually or bi-annually whether to raise the debt ceiling (Russia doesn't have one, in fact only the U.S. and Denmark do, and Denmark revises theirs every year with their budget), what if our government just drew from its savings?

reply to post by Samtzurr

In very simple terms, the USA government is printing fake money, like there are no consequences to it. This lowers the value of all dollars. They took the dollar off the gold standard many years ago, and the only worth it has is the faith one has in the American government. Once the world stops using the dollar as the reserve currency you can expect to see its buying power drop like a brick. This will result in inflation as one's buying power is diminished. It's coming, Obama has seen to that.

In very simple terms, the USA government is printing fake money, like there are no consequences to it. This lowers the value of all dollars. They took the dollar off the gold standard many years ago, and the only worth it has is the faith one has in the American government. Once the world stops using the dollar as the reserve currency you can expect to see its buying power drop like a brick. This will result in inflation as one's buying power is diminished. It's coming, Obama has seen to that.

reply to post by Samtzurr

dailyreckoning.com...

Printing to much money causes inflation, when out of control, it causes things to get really expensive because there are "too many dollars chasing fewer goods". In order to tame inflation, the "insert central bank" will have to raise interests rates to make it more expensive to borrow money. Less money floating around increases the value of the currency (Less dollars for more goods). The threat of Derivatives imploding is that there are hundreds of trillions of dollars in exposure but not enough money in the world to bail them out. It's a bankers game so I say screw them.

dailyreckoning.com...

Printing to much money causes inflation, when out of control, it causes things to get really expensive because there are "too many dollars chasing fewer goods". In order to tame inflation, the "insert central bank" will have to raise interests rates to make it more expensive to borrow money. Less money floating around increases the value of the currency (Less dollars for more goods). The threat of Derivatives imploding is that there are hundreds of trillions of dollars in exposure but not enough money in the world to bail them out. It's a bankers game so I say screw them.

It's not so much that the interest rates must rise as it is that the Fed must abide by it's mandate which means full employment and controlling

inflation. Right now the Fed feels that inflation is not a concern due to the slow economy however as the economy improves inflation will kick in and

then the Fed will have to allow interest rates to rise in order to control inflation.

So why does there have to be inflation? Well it's simple really. Why do prices go up? There is more demand than supply right. Well if you start pumping money into the system, then naturally there will be more demand. Now if the consumers don't get the money since they can't find a job (which means that the money is in the wrong hands) then of course the effects of the added money will not be felt at least not right away. However one way or another there will be inflation (the money will be invested which will cause jobs to be created and those new workers will spend money causing more jobs to be created) and then the Fed will allow interest rates to rise to avoid hyper inflation. It could be too late at that point but that's debatable.

This will be catastrophic for the American government as most know since they are at the highest debt levels ever (even the smallest increase in interest rates will be crippling) and it's only getting worse. I believe it will be like this. The government cannot borrow from the fed directly as there is a separation as small as it may be. However I believe the higher interest rates will bring the American government to it's knees and the Fed will declare an emergency much like they did with AIG and then they can do whatever they want and then there will be (a) direct interest free loan(s) to the government. I guess the question will be what will it do to the dollar? If the dollar makes it out then then all will be well but it could spell the end of the greenback and then will come the American economy with it. To me it will come down to opinion because whether the Fed loans directly or indirectly it doesn't matter. It's all the same and actually a direct loan might have less inflation risk. When the fed buys bonds, it causes the stock market to rise (money moves from bonds to stocks) causing the market to rise. This puts more money in the economy which can cause inflation but in theory there is no stock market rise with a direct loan so on a basic level it could be better. What could happen though is that such a direct loan would upset a lot of people and could throw the economy into a downward spiral. We will just have to wait and see.

So why does there have to be inflation? Well it's simple really. Why do prices go up? There is more demand than supply right. Well if you start pumping money into the system, then naturally there will be more demand. Now if the consumers don't get the money since they can't find a job (which means that the money is in the wrong hands) then of course the effects of the added money will not be felt at least not right away. However one way or another there will be inflation (the money will be invested which will cause jobs to be created and those new workers will spend money causing more jobs to be created) and then the Fed will allow interest rates to rise to avoid hyper inflation. It could be too late at that point but that's debatable.

This will be catastrophic for the American government as most know since they are at the highest debt levels ever (even the smallest increase in interest rates will be crippling) and it's only getting worse. I believe it will be like this. The government cannot borrow from the fed directly as there is a separation as small as it may be. However I believe the higher interest rates will bring the American government to it's knees and the Fed will declare an emergency much like they did with AIG and then they can do whatever they want and then there will be (a) direct interest free loan(s) to the government. I guess the question will be what will it do to the dollar? If the dollar makes it out then then all will be well but it could spell the end of the greenback and then will come the American economy with it. To me it will come down to opinion because whether the Fed loans directly or indirectly it doesn't matter. It's all the same and actually a direct loan might have less inflation risk. When the fed buys bonds, it causes the stock market to rise (money moves from bonds to stocks) causing the market to rise. This puts more money in the economy which can cause inflation but in theory there is no stock market rise with a direct loan so on a basic level it could be better. What could happen though is that such a direct loan would upset a lot of people and could throw the economy into a downward spiral. We will just have to wait and see.

edit on

10-11-2013 by bfis108137 because: (no reason given)

new topics

-

Only two Navy destroyers currently operational as fleet size hits record low

Military Projects: 7 hours ago

top topics

-

George Stephanopoulos and ABC agree to pay $15 million to settle Trump defamation suit

Mainstream News: 12 hours ago, 17 flags -

Only two Navy destroyers currently operational as fleet size hits record low

Military Projects: 7 hours ago, 7 flags

active topics

-

-@TH3WH17ERABB17- -Q- ---TIME TO SHOW THE WORLD--- -Part- --44--

Dissecting Disinformation • 3694 • : RelSciHistItSufi -

They Know

Aliens and UFOs • 87 • : UsernameNotFoundAgain -

Encouraging News Media to be MAGA-PAF Should Be a Top Priority for Trump Admin 2025-2029.

Education and Media • 90 • : Coelacanth55 -

Nov 2024 - Former President Barack Hussein Obama Has Lost His Aura.

US Political Madness • 16 • : Coelacanth55 -

Mood Music Part VI

Music • 3735 • : BrucellaOrchitis -

A Bunch of Maybe Drones Just Flew Across Hillsborough County

Aircraft Projects • 83 • : charlyv -

The Mystery Drones and Government Lies

Political Conspiracies • 72 • : tarantulabite1 -

Only two Navy destroyers currently operational as fleet size hits record low

Military Projects • 1 • : alwaysbeenhere2 -

A priest who sexually assaulted a sleeping man on a train has been jailed for 16 months.

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 30 • : alwaysbeenhere2 -

George Stephanopoulos and ABC agree to pay $15 million to settle Trump defamation suit

Mainstream News • 11 • : WeMustCare

3