It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

26

share:

It is a Plants Life

If you don't believe that plants are important, this thread is probably not for you. If you don't recognize their medicinal properties, or the fact that they are the true "rainmakers" of our world, you probably won't have any interest in what follows. It's ok, I didn't realize the true extent of their value either before I started researching them. It was only through a few weeks of reading that I began to understand just who really controls the world...and it's not humans, it's plants.

The next few pages will go through some history of plants, Darwin's "abominable mystery", a bit of evolution, their role in climate change, medicine, if plants are intelligent, their evil side, and finally, a recap portion. Peppered throughout will be some "facts" or "did you know" information at the beginning of each new section. A couple of youtube videos and some pics as well.

Hopefully you find out a few things you didn't know, as well as maybe you can share with me a few things I didn't know or missed. So, let's began at the beginning...

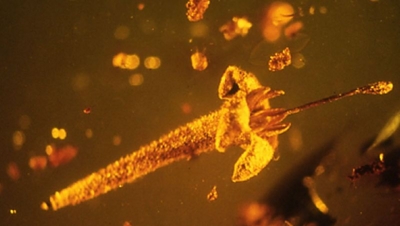

Flower captured in amber

The Beginning

There are an estimated 80,500 plants that have yet to be discovered. Of those over 70,000 are angiosperm (flowering plants)

The funny thing is, instead of humans stepping out of primordial ooze, it was actually plants that did. Ok, so, the ooze was water and the plants were algae, but still, it is the same thing (but different). Plants are thought to have spent millions of years as algae living in aquatic environments. Probably pretty happy there, hanging out, doing their thing. But eventually they branched out and migrated to land.

The algae responsible for bringing that migration, the great, great, great (add a few hundred more greats here) grandfather of all plants is Chlorophyta. After spending millions of years in the water, it evolved. The first land plants are thought to have all come from this one. But, Chlorophyta didn't do it alone...it had some accomplices. A bacteria and a protozoan-like host:

suggests what microscopic parts would have been present in this common ancestor based on findings by Dana Price of Rutgers University and his colleagues, who examined the genome of a freshwater microscopic algae and determined that it showed that algae and plants are derived from one common ancestor. This ancestor formed from a merger between some protozoan-like host and cyanobacterium, a kind of bacteria that use photosynthesis to make energy, that "moved in" and became the chloroplast of this first alga. ...

They went from water algae to land algae basically. There were supposedly 4 different types of freshwater algae (scientists say it had to be fresh water algae that became plants, not sea algae) that invaded land, but the other three couldn't adapt, so, only the one type of algae (Chlorophyta) got to be a plant. The other three remained land algae or died off.

Scientists beleive that from that one little bacteria the first plants evolved into what are known as Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts). Bryophytes were, to the best of my understanding, basically ground cover. They are also nonvascular plants:

These plants have no vascular tissue, so the plants cannot retain water or deliver it to other parts of the plant body ...

They hung out like that for a bit (a few million years, give or take a zero) and then some of them decided to "update their wardrobe". Lycophytes came into existence, they were basically moss that grew more vertical and less horizontal. These plants include club mosses, spike mosses, and quillwort. They are believed to be the first vascular plants, followed closely behind by ferns, which are classified as Pterophytes.

Ferns grew even higher than their predecessors. Because of the CO2 rich atmosphere, they grew to be as big as dinosaurs! Ok, not really, but they grew to really big (tree like) heights and were present during the dinosaur era. Which is a pretty big deal, considering how small most ferns are today.

From Pterophytes plants eventually developed seeds. Those plants are called Gymnosperms. They are also vascular plants. Their seeds were important because they allowed the plants to basically migrate to areas that were farther away. This kind of changed the whole reproduction gig for plants because before seeds, plants used spores and it is my understanding that they were more localized.

Gymnosperms are redwoods, pines, furs, Ginkgo, and have about 4000 different species spread all over the world. Of the two types, gymnosperms are the oldest. They are long-lived plants that were present on this Earth around 390 million years ago during the Devonian period. They are the largest and tallest plants on this Earth and they have naked seeds or are not fruit bearing trees. Their seeds are found on the surface of scales, leaves, and also in cone form. They rely on the wind to reproduce. These plants are mostly used for lumber, paper, and other products made from wood.

Well, they almost have it all. Nature decided to improve upon the plant kingdom one more time. The last species is called Angiosperm and they are your flowering plants. The kind that insects pollinate. They have over 250,000 species in the world. They have shorter life spans than the gymnosperms. They have seeds that are enclosed within an ovary (usually a fruit). They are fruit or flower bearing plants and usually do not achieve the height like gymnosperms do. Their reproduction mostly relies on animals. Angiosperms are used mainly for medicine, food, and clothing

To get to these last two plant species they had to make some huge changes to their physical and genetic makeup. Which, for all you "skimmers", I'm just gonna list the general differences/timeline for each group below. There are more detailed changes to be found at the links you can read through if you wish to. This should cover enough for all those that just want to get the basic idea of a plants evolution:

- Chlorophyta - Water Algae that the land dwelling plants came from

- Bryophytes - first non vascular land dwelling plants/ground cover

- Lycophytes - First vascular seedless plants (slightly vertical growing)

- Pterophytes - Ferns the grew as big as dinosaurs or...vertical growing vascular seedless plants

- Gymnosperms - first vascular unenclosed seed bearing plants

- Angiosperms - first vascular flower bearing enclosed seed plants

Continued...

edit on 13-3-2018 by blend57 because: Always an Edit! :/

The Beginning Continued

There is a correlation between rainstorms and disease outbreaks among plants. Historical weather records suggest that rainfall may scatter rust and other pathogens throughout a plant population ...

Gymnosperms and Angiosperms are what we have all over the world today. They are the modern version of plants. And that is the end of the history of plants. I generalized it as much as I could. As I said, you can find more info in the links, and I'm sure I left out some stuff along the way, but it is enough to give you an idea about how they developed/came to into existence.

One final thing to note: Plants were on this planet way before any animals were. They are the first species to populate the world and have survived (in one form or another) through all the extinction level events. Yep, when the dinosaurs got wiped out, the plants lived and adapted to suit the new climate. They've outlived every other species so far (in years on the Earth) and have managed to populate almost every corner of the world including deserts, caves, mountains, oceans and tropical climates.

On to the next section....

The Abominable Mystery

Darwin, when he wrote his book The Origin of Species, documented his concerns with regards to the origins of plants. He was specifically interested in one classification, the most recent addition to the plant world, the Angiosperm. Many probably know that the angiosperm had the potential to ruin or severely damage Darwin's theory of evolution because they just appeared in history and did so in huge numbers. How did they spread so fast, show up in so many different varieties, and where did they all come from originally? This is a dilemma that he needed to solve to make his theory work.

If you beleive in slow, gradual evolution like Darwin did, angiosperms kind of put a damper on those beliefs. At the time, he couldn't trace their origins back to the earlier plants. The earliest forests had more species like were more like mosses and algae. All the other plants could be traced back to the first land plants, bryophytes. But then, out of no where pops up the Angiosperms (flowering plants) about 125 million years ago. That's what perplexed Darwin... so many different species in such a short time and no way to link them to the plants evolution line. He spent a good deal of his later life trying to figure out their origins. And in the end, the mystery was left unsolved....even now the answer remains as elusive as it was back in his day.

It was Darwin that coined the phrase abominable mystery in one of his letters he wrote to a colleague:

The phrase stuck and can be seen used today by Paleo-botanists and botanists alike because the mystery still hasn't been solved. There are a lot of theories, but no one has found "the missing link". The one plant species that showed the transition from gymnosperms to angiosperms. We have found the earliest known angiosperm though, which seems to at least offer hints the their origins.

Even if we did find the missing link, we still would have the issue of how they evolved into so many different varieties so quickly. There are quite a few theories out there that have been thrown around. I'm not sure if any of them are right. Or maybe all of them are right and need to be combined. Probably each one of them happened at some point in the angiosperms evolution, but we still have no solid answers (only best guesses) as to where the species derived from.

Continued...

There is a correlation between rainstorms and disease outbreaks among plants. Historical weather records suggest that rainfall may scatter rust and other pathogens throughout a plant population ...

Gymnosperms and Angiosperms are what we have all over the world today. They are the modern version of plants. And that is the end of the history of plants. I generalized it as much as I could. As I said, you can find more info in the links, and I'm sure I left out some stuff along the way, but it is enough to give you an idea about how they developed/came to into existence.

One final thing to note: Plants were on this planet way before any animals were. They are the first species to populate the world and have survived (in one form or another) through all the extinction level events. Yep, when the dinosaurs got wiped out, the plants lived and adapted to suit the new climate. They've outlived every other species so far (in years on the Earth) and have managed to populate almost every corner of the world including deserts, caves, mountains, oceans and tropical climates.

On to the next section....

The Abominable Mystery

Darwin, when he wrote his book The Origin of Species, documented his concerns with regards to the origins of plants. He was specifically interested in one classification, the most recent addition to the plant world, the Angiosperm. Many probably know that the angiosperm had the potential to ruin or severely damage Darwin's theory of evolution because they just appeared in history and did so in huge numbers. How did they spread so fast, show up in so many different varieties, and where did they all come from originally? This is a dilemma that he needed to solve to make his theory work.

If you beleive in slow, gradual evolution like Darwin did, angiosperms kind of put a damper on those beliefs. At the time, he couldn't trace their origins back to the earlier plants. The earliest forests had more species like were more like mosses and algae. All the other plants could be traced back to the first land plants, bryophytes. But then, out of no where pops up the Angiosperms (flowering plants) about 125 million years ago. That's what perplexed Darwin... so many different species in such a short time and no way to link them to the plants evolution line. He spent a good deal of his later life trying to figure out their origins. And in the end, the mystery was left unsolved....even now the answer remains as elusive as it was back in his day.

It was Darwin that coined the phrase abominable mystery in one of his letters he wrote to a colleague:

I have just read Ball’s Essay. It is pretty bold. The rapid development as far as we can judge of all the higher plants within recent geological times is an abominable mystery. Certainly it would be a great step if we could believe that the higher plants at first could live only at a high level; but until it is experimentally [proved] that Cycadeae, ferns, etc., can withstand much more carbonic acid than the higher plants, the hypothesis seems to me far too rash. Saporta believes that there was an astonishingly rapid development of the high plants, as soon [as] flower-frequenting insects were developed and favoured intercrossing. I shd like to see this whole problem solved. I have fancied that perhaps there was during long ages a small isolated continent in the S. hemisphere which served as the birthplace of the higher plants—but this is a wretchedly poor conjecture. —Excerpt of a letter written by Charles Darwin on 22 July 1879 to Joseph Hooker ...

The phrase stuck and can be seen used today by Paleo-botanists and botanists alike because the mystery still hasn't been solved. There are a lot of theories, but no one has found "the missing link". The one plant species that showed the transition from gymnosperms to angiosperms. We have found the earliest known angiosperm though, which seems to at least offer hints the their origins.

The Amborella plant, found in the rain forests of New Caledonia in the South Pacific, has a unique way of forming eggs that may represent a critical link between the remarkably diverse flowering plants, known as angiosperms, and their yet to be identified extinct ancestors, said CU-Boulder Professor William "Ned" Friedman. Angiosperms are thought to have diverged from gymnosperms -- the dominant land plants when dinosaurs reigned in the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods -- roughly 130 million years ago and have become the dominant plants on Earth today. ...

Even if we did find the missing link, we still would have the issue of how they evolved into so many different varieties so quickly. There are quite a few theories out there that have been thrown around. I'm not sure if any of them are right. Or maybe all of them are right and need to be combined. Probably each one of them happened at some point in the angiosperms evolution, but we still have no solid answers (only best guesses) as to where the species derived from.

Continued...

Abominable Mystery Continued

In the Netherlands, in 1634, a collector paid 1,000 pounds of cheese, four oxen, eight pigs, 12 sheep, a bed, and a suit of clothes for a single bulb of the Viceroy tulip.

Some of the theories:

The first theory is that insects were responsible for the accelerated spread of and cultivation of the angiosperm. Which, would be great and makes sense, but, the first flowering plants weren't all that colorful or even beautiful. That adaptation (beautiful colors and flowers) happened a bit after the sudden growth spurt. It might have been another adaptation that occurred later to make the flowers so colorful that the insects would notice and pollinate the plants. So far, although a good thought, probably not the reason angiosperms populated the Earth in so many different varieties. Yep, it probably helped them to mass populate, but it doesn't really solve the quick evolution/adaptation dilemma.

Another theory: They were already present on the Earth and migrated from a secluded island into other areas where they were able to mass produce. They adapted to many different climates quickly and "took over the world!" (this was basically Darwin's theory).

The problem with this theory (Darwin's part anyways) is that we have fossil records of angiosperms on many different continents since his time. We've still not found a direct link to gymnosperms, nor have we figured out how they massed migrated, but we do know that there are/were angiosperms in other areas of the world and not just on one secluded island.

Another major issue with the secluded island theory is that the size of the geographical area determines the biodiversity of a particular flowering plant. Which means that being stuck on a secluded island would cause the flowering plants to have little to no biodiversity. And that also means that, for now, this theory is still questionable.

Next we have the idea that they were ferns that were able to produce smaller cells, which allowed them to become more efficient at photosynthesis and collecting water. They do have smaller cells than the gymnosperms, and are more effective at photosynthesis. The mystery with this one is how were they able to develop/evolve smaller cells so quickly, what prompted the change?

Drs. Jana Vamosi and Steven Vamosi of the Department of Biological Sciences have found through extensive statistical analysis that the size of the geographical area is the most important factor when it comes to biodiversity of a particular flowering plant family.

The researchers were looking at the underlying forces at work spurring diversity -- such as why there could be 22,000 varieties of some families of flowers, orchids for example, while there could be only forty species of others, like the buffaloberry family. In other words, what factors have produced today's biodiversity?

"Our research found that the most important factor is available area. The number of species in a lineage is most keenly determined by the size of the continent (or continents) that it occupies," says Jana Vamosi. ...

There is another theory that coincides with the previous one: genome doubling. I'm just gonna quote because they explain it better than I do:

The first angiosperms must have evolved from one of the gymnosperm species that dominated the world at the time. The Amborella genome suggests that the first angiosperms probably appeared when the ancestral gymnosperm underwent a 'whole genome doubling' event about 200 million years ago.

Genome doubling occurs when an organism mistakenly gains an extra copy of every one of its genes during the cell division that occurs as part of sexual reproduction. The extra genetic material gives genome doubled organisms the potential to evolve new traits that can provide a competitive advantage. In the case of the earliest angiosperms, the additional genetic material gave the plants the potential to evolve new, never-before-seen structures – like flowers. The world's flora would never be the same again....

Again, the genome doubling theory has the same issue as the smaller cell structure theory: how did they do it so quickly and become so diverse? I'm even willing to believe all of these solutions to angiosperm's evolution happened (maybe at different points in evolution), but still you have to wonder, because they appeared so quickly and in huge varieties, is quick evolution possible? What would make a plant do such a thing? Was it a forced evolution? I know Darwin won't like it, but maybe that is the answer: they developed so quickly because there was a need. Sort of a live or die scenario and they chose to live. But that is just my personal thoughts, I have no proof to back that up.

Continued...

Plants Linked to Climate Change Part 1

There is a hidden map inside plants. When a group of scientists asked themselves why rose petals have rounded ends while their leaves are more pointed and they noticed something unusual. Their study revealed that the shape of petals is controlled by a hidden map located within the plant’s growing buds.

Leaves and petals perform different functions related to their shape.

With each stage of the development comes something that coincides with that development...major climate changes. Every time plants made an adaptation, there was a major switch in the climate as well. When they first invaded land, the climate was dry and barren (so it is thought). Most scientists believe that it was mostly desert lands. This made it rough for the bryophytes to survive (thus the 1 out of 4 algae adaptation).

Once they did take hold, the climate became more lush and tropical. But this can't really be proven, the only thing evidence suggests is that the changes were made around climatic conditions. Which leads us to the age old question: what came first, the chicken or the egg? Did the climate change because of plants evolving or did plants evolve because of climate change? Although some believe that climate change was caused by plants, I think it was the other way around...plants adapted to climate change.

This also goes back to Darwin's theory of evolution...is there a time when evolution speeds up? A forced adaptation? Darwin thought that it was slow and steady. Always slow and steady. Maybe that is true for the most part. But I bet there are times when the process is accelerated.

The team set out to identify the effects that the first land plants had on the climate during the Ordovician Period, which ended 444 million years ago. During this period the climate gradually cooled, leading to a series of 'ice ages'. This global cooling was caused by a dramatic reduction in atmospheric carbon, which this research now suggests was triggered by the arrival of plants.

Among the first plants to grow on land were the ancestors of mosses that grow today. This study shows that they extracted minerals such as calcium, magnesium, phosphorus and iron from rocks in order to grow. In so doing, they caused chemical weathering of Earth's surface. This had a dramatic impact on the global carbon cycle and subsequently on the climate. It could also have led to a mass extinction of marine life.

The research suggests that the first plants caused the weathering of calcium and magnesium ions from silicate rocks, such as granite, in a process that removed carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, forming new carbonate rocks in the ocean. This cooled global temperatures by around five degrees Celsius.

In addition, by weathering the nutrients phosphorus and iron from rocks, the first plants increased the quantities of both these nutrients going into the oceans, fuelling productivity there and causing organic carbon burial. This removed yet more carbon from the atmosphere, further cooling the climate by another two to three degrees Celsius. It could also have had a devastating impact on marine life, leading to a mass extinction that has puzzled scientists. ...

Plants caused the first ice age just by becoming land dwellers and sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and rocks. That was the theory in 2012. And, for all intents and purposes this could be right...but new findings suggest that plants adapted to the conditions of cooler weather and they actually saved us from having a longer ice age. This article from 2017 states that plants prevented or reversed it:

Human civilization happened because something reversed a cooling trend about 20,000 years ago.

A new study, published today in Nature Geoscience, has a hypothesis what that something was: plants. Or, more specifically, a complicated process in which plants wear down certain kinds of rocks, and how those rocks remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they wear down—leaving just enough CO2 out there to trap solar warmth, and gradually bring summer back.

Attached to the roots of many plants are microscopic fungi called mycorrhizae that, among other things, help increase the rate at which silicate rocks weather. When the weather gets cold, the plants die off, the fungi do less weathering—the weather itself stops raining so much—and the levels of CO2stay stable.

But wait, there’s more. Another type of microscopic ocean critter called phytoplankton absorb CO2 at the ocean surface and sock it away in the deep ocean when they die and sink. Although today there is plenty of CO2 available at the surface, when CO2 was extremely low these little guys would have grown more slowly. As a result, less sinking of dead little critters into the deeps would have left more CO2 at the ocean surface where it could, wave by wave, flush back into the atmosphere. And unlike the extremely slow plant-weathering process Pagani suggested, changes in phytoplankton could happen in the geological blink of an eye—only a few hundred years. ...

So we are back to that question again: did plants cause ice ages or prevent/reverse them? Did they adapt to the weather conditions or was it because they adapted that the weather conditions occurred? One scientist believes that plants definitely are capable of manipulating climate change. Through studying ocean plant behaviors, he determined that sea plants slow down oceanic acidification:

Researchers are finding that kelp, eelgrass, and other vegetation can effectively absorb CO2 and reduce acidity in the ocean. Growing these plants in local waters, scientists say, could help mitigate the damaging impacts of acidification on marine life.

The climate of our Earth is changing once more . So, with that change, we should be able to determine what role plants play in the process.

So far, it seems that plants are adapting to the new weather conditions. They aren't just making small changes either. Some of them are evolving at a genetic level. As the change in CO2 occurs, there are several changes taking place. One of them is reproduction. More plants are growing in some areas. The other is migration, they are figuring out how to get to areas that are similar to their normal habitat, sensing their current area has changed in some way. Some are making changes internally to combat climate change as well.

Continued...

edit on 13-3-2018 by blend57 because: Always an Edit! :/

Plants Linked to Climate Change Part 2

Dating back at least a thousand years, ancient cultures used moss to help cleanse and heal their wounds. So, when Allied surgeons ran out of cotton on the battlefield during WWI, they turned to moss as a potential stopgap. Leveraging peat moss’ high absorbency and antiseptic properties, Europe and America produced millions of moss bandages to treat their wounded over the course of the war.

Both of the current species on the planet are developing /adapting because of climate changes. Angiosperms or flowering plants make up the majority of our foliage. There have already been some documented changes with at least one plant:

New research shows that seasonal plants can adapt quickly--even genetically--to changing climate conditions and reveals various mechanisms by which they control their growing response when the weather shifts. The studies suggest, however, that longer-lived plants have a tougher time going with the flow.

Other research in Europe has shown that plants can shift another mechanism that controls their response to climate: vernalization, or the length of the cold snap required before a plant will respond to a warm spell as a growth signal. Caroline Dean of the John Innes Centre in Norwich, England, and her colleagues studied this response in the ubiquitous Arabidopsis thaliana, or thale cress. Such plants in Sweden require nearly four times as long a winter as their counterparts in England--14 weeks versus four, respectively--before they will interpret warmth as a signal to grow. ...

Now we have an idea that fast evolution could occur when the situation calls for it. We also can determine somewhat how the flowering plants managed to become so diverse so quickly. And we understand that plants probably are both the cause and the cure of climate change. They work symbiotically with the world and the weather to manipulate their environment for survival purposes.

Another proof of fast evolution for you. Even though they say that longer-lived plants will have a hard time adjusting, I wouldn't count out gymnosperms (pines, redwoods, and such) just yet. Even though they only have around 4000 species compared to the over 250 thousand species of angiosperm, they are still adapting and may be able to make it through the current climate shift.

Albino Redwoods

As I was searching through websites, I found a new species of gymnosperm that seems to have developed in California. For the past hundred years or so, these redwood trees have learned how to survive living off of toxins in the soil. They also feed off of normal redwood trees. They have found a way to live in hostile environments and are called the ghosts of the forest. And they are rare, there are only 400 in existence that all can be found in California's coastal forests.

The interesting part is how they survive: they basically barter/trade with the other redwood plants:

He found that the albino needles were saturated with what should have been a deadly cocktail of cadmium, copper and nickel. On average, white needles contained twice as many parts per million of these noxious heavy metals as their green counterparts; some had enough metals to kill them ten times over. Moore thinks faulty stomata — the pores through which plants exhale water — are responsible: plants that lose liquid faster must also drink more, meaning that the albino trees have twice as much metal-laden water running through their systems.

“It seems like the albino trees are just sucking these heavy metals up out of the soil,” Moore said. “They're basically poisoning themselves.”

Moore's theory — which he presented at a redwood conference last month and hopes to publish next year — is that albino redwoods are in a symbiotic relationship with their healthy brethren. They may act as a reservoir for poison in exchange for the sugar they need to survive.

...

This could possibly be fast evolution as well as proof of intelligence. Why would redwoods feel the need to develop in such a manner? Learning how to survive in un-survivable conditions, using poisons as their main source of food. Both the normal redwoods and the albino redwoods cooperating with one another to make sure each one lives.

Continued...

edit on 13-3-2018 by blend57 because: Always an Edit! :/

Plants Cause Climate Change Part 3

Hundreds of years ago, when Vikings invaded Scotland, they were slowed by patches of wild thistle, allowing the Scots time to escape. Because of this, the wild thistle was named Scotland’s national flower.

So, as our world changes, so do plants (and animals ) to accommodate those changes. Here is another study done that links plants to climate change. But this one talks about their impact on climate change in the future. I'm under the impression that we have reached that future and although it isn't an overnight change, we are witnessing the effects of climate change in the now.

“Plant growth can have a considerable effect on the climate,” says Wolfgang Buermann, a geographer at Boston University. He explains that there are several ways in which plants can alter the temperature of the Earth’s atmosphere. Through the process of photosynthesis, plants use energy from the sun to draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and then use it to create the carbohydrates they need to grow. Since carbon dioxide is one of the most abundant greenhouse gases, the removal of the gas from the atmosphere may temper the warming of our planet as a whole.

Plants also cool the landscape directly through the process known as transpiration. When the surrounding atmosphere heats up, plants will often release excess water into the air from their leaves. By releasing evaporated water, plants cool themselves and the surrounding environment. “It’s like sweating. When you sweat you cool the surface of your skin,” says Buermann. Over a forest canopy or a vast expanse of grassland, large amounts of transpiration can markedly increase water vapor in the atmosphere, causing more precipitation and cloud cover in an area. The additional cloud cover often reinforces the cooling by blocking sunlight.

Because of these processes, many researchers believe plants may have a sizable impact on global climate in the future. As humans continue to generate carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, the Earth’s surface will likely warm at a faster rate than it has in a thousand years. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Earth is likely to warm another 1.4 degrees to 5.8 degrees by the end of this century (IPCC 2001). Needless to say, such big changes in the climate would likely alter vegetation growth all over the world.

...

Having the ability to directly impact our future climate and also theorized to be the reason we had climatic changes in the past, plants are pretty important to our world and environment. You might think that I'm talking only about angiosperms. I'm not, every plant contributes to the Earths climate. Which, I'm sure all of you knew...but sometimes we don't stop and think about it. It's not something that we keep in the forefronts of our minds. So, just a bit of a reminder I guess.

I bolded the last sentence because I feel it is kind of a important one that shows that we, in our generation, will be seeing some very real adaptations in plants as the climate continues to change. Probably one of the biggest markers in how quickly our world is changing will be how quickly the plants change. Some of the changes will be that plants go extinct. Yep, we will see some species fade away just like animals have been doing.

Another possibility is they will adapt in size and location. The normal flowering buds you see around your area may not be there eventually. Invading plants may take over because the environment is more suitable to them. And, you could see a larger population of one plant versus another:

Varieties of Mediterranean thyme (Thymus vulgaris) produce oils with different chemical compositions, and the ones with stronger smelling compounds like phenols are more effective at deterring herbivores. Producing phenols typically comes at a cost, though, as these plants are more sensitive to freezing. But in southern France’s Saint-Martin-de-Londres basin, winters are getting warmer. Since the 1970s, the basin has seen fewer freezing nights during the cold season.

Looking at 24 populations across the basin in 1974 versus 2010, one study found an increase in the proportion of plants that produce phenolic compounds. These plants are even popping up in areas where they didn’t grow in the 1970s. Since the plant’s genes determine the chemical composition of its oils, it’s likely that genetic changes are behind wild thyme’s response to warmer winters ...

Ok...before everyone starts yelling about global warming and climate change...this thread isn't about that. It's about plants. But, I still needed to include that portion because it does show that plants are still evolving and keeping pace with climate changes. And, you are witnessing evolution in action if all that up there is true. We often see little changes, but rarely do we see species "mutate" within one humans lifetime. Some scientists think that plants will have to adapt fast in order to keep up with the climatic changes. We may be able to witness some of those moments when the changes take place. As in, we will see new species emerge and others die off.

Continued...

Plants in Medicine

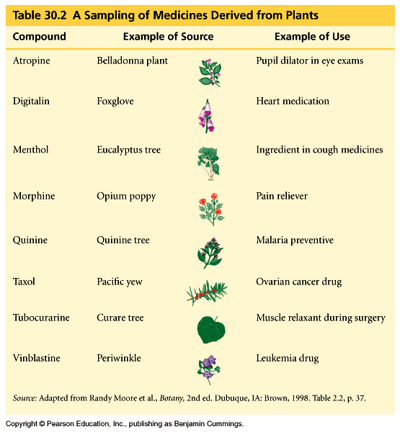

40% of our total medicines are derived from plants and over 70% of new medications are derived from plants

Throughout the ages, humans have relied upon plants to heal their ailments. The discovery of herbal medicine is thought to have happened through humans watching animals cure themselves by eating certain plants.

There are historic sites in Iraq that show Neanderthals used yarrow, marsh mallow, and other herbs more than 60,000 years ago. Our ancestors noticed that animals were using herbs when they were ill. These uses were observed closely. Later they were incorporated into prehistoric shamanism, and then into medicine....

The very first documented use of plants in medicine comes from the Sumerians:

The oldest written evidence of medicinal plants’ usage for preparation of drugs has been found on a Sumerian clay slab from Nagpur, approximately 5000 years old. It comprised 12 recipes for drug preparation referring to over 250 various plants, some of them alkaloid such as poppy, henbane, and mandrake....

From there we continue to use plants as our primary source of treatment for medical conditions until, well, we still use them for treatments today. The 19th century is where we see an explosion of modern medicine though. That is when we gained more of evolution, psychiatry, the beginnings of genetics, and immunology.

This is when we started to produce our own drugs/treatments to ailments and using them in addition to or lieu of plants. Medicine discoveries kind of stalled after a while in 2004. We were able to make simple compounds but not the complicated ones that mother nature already puts out:

Reuters, which reviewed the new paper, reported that “drug discovery hit a 24-year low in 2004, with just 25 unique compounds known as new chemical entities introduced that year.” Lead author, David Newman of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s natural products branch, said the advent of new drug discovery techniques in recent years diverted pharmaceutical company resources away from natural sources of new drug compounds.

“Chemists started making libraries of hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds. But they were simple compounds,” Reuters quoted Newman as saying via telephone. “Mother Nature doesn’t make simple compounds. Mother Nature wants compounds that fit into particular places.” ...

So, we've gone back to using plants and trying to discover their healing properties again. Plants get all their nutrients and change/adapt according to the environment. Bacteria change and adapt according to their environment as well. It makes sense that plants would have the cure for most diseases. Matter of fact, the development of cures for cancer kind of prove that point:

Overall, say the researchers, “half of all anti-cancer drugs introduced since the 1940s are either natural products or medicines derived directly from natural products.”

The following 2 images list some plants and what they are used for in medicine. This is, by no means, a full list. As over 40% of our medicines come from plants, this is only a small sampling:

The first medicines were derived from plants. Maybe we don't realize or haven't stopped to think about the fact that we are still creating a good portion of our medicines from them. This is why plants dying off is a big deal. Yep, we can synthesize a lot of what they offer, but, if you read the first "fact" I put out there about 80,500 plants still needing to be discovered, well, that kind of puts things into perspective a bit. What if one of those undiscovered plants has the cure for all cancer? And, before we discover it, due to climate change, it goes extinct? Now we are looking at the whole climate change thing from a new perspective, or we should be.

If a majority of our medicines are still coming from plants, we still have the opportunity to advance medicine by finding undiscovered ones. But if they die off or genetically change, we may never be able to cure some of those diseases or, at least, it will take us longer to do so. So, it becomes a bit more important now that we try to either discover the rest of the plants before the climate changes too much or we slow down climate change somehow until we do discover the rest of the plants (if that is even possible, I am unsure).

For all of these reasons, the study and conservation of medicinal plant (and animal) species has become increasingly urgent. The accelerating loss of species and habitat worldwide adds to this urgency. Already, about 15,000 medicinal plant species may be threatened with extinction worldwide. Experts estimate that the Earth is losing at least one potential major drug every two years. ...

Now, before I go any further, I must say that I think modern medicine is important and I'm in no way advocating that you ditch it for natural cures. But I also have to say that I think it is important that modern medicine utilizes all the tools it has available (both natural and synthetic) in order to combat disease. I imagine that by combining the two (making medicines out of natural products and maybe enhancing their properties through scientific advancements) we will see better results in treatments. Which, as I said, it seems like they are starting to do again.

Also, you should seek out medical treatment and listen to what your doctor says with regards to your condition, but your doctor should also listen to what you say as well. The first visit is always a consultation and sharing of information. You know your body better than s/he does, but they know the science better than you do. That is where, if done properly, the benefit of the medical world comes into play. (this is my own opinion, yours may be different).

Continued....

Intelligent Plants? Part 1

Eucalyptus contains a kind of oil that is so flammable that the trees can actually explode when they catch fire

Personally I feel any species that has the capabilities to potentially control the climate, and by association control the development of other species, is intelligent. It seems like plants have surpassed us in and possibly perfected weather modification. Thankfully I don't have to prove they are intelligent, science has done that for me:

Depth analysis of plant consciousness since the turn of the (new) millennium is finding that their brain capacity is much larger than previously supposed, that their neural systems are highly developed—in many instances as much as that of humans, and that they make and utilize neurotransmitters identical to our own. It is beginning to seem that plants are highly intelligent, feeling beings—perhaps as much or even more so than humans in some instances. (They can even perform sophisticated mathematical computations and make future plans based on extrapolations of current conditions. The mayapple, for instance, plans its growth two years in advance based on weather patterns....

So far, plants have been found to have emotion, feel pain, pre-plan their growth patterns, have memory, communicate, help other plants, and have complex neural systems. We also have been able to find their brain. Their brain is located in the root system. With everything we've discovered so far, some scientists beleive that a plants intelligence is close to or on par with a human beings. Now, I don't know if that is the case or not, but they make some valid claims as to why.

While humans and many other animals, for example, have a specific organ, the brain, which houses its neuronal tree, plants use the soil as the stratum for the neural net; they have no need for a specific organ to house their neuronal system. The numerous root apices act as one whole, synchronized, self-organized system, much as the neurons in our brains do. Our brain matter is, in fact, merely the soil that contains the neural net we use to process and store information. Plants consciously use the soil itself to house their neuronal nets. This allows the root system to continue to expand outward, adding new neural extensions for as long as the plant grows.

In addition, the leaf canopy also acts as a synchronized, self-organized perceptual organ, which is highly attuned to electromagnetic fields. It can be viewed, in fact, as a crucial subcortical portion of the plant brain.

For their neural networks to function and demonstrate consciousness, plants use virtually the same neurotransmitters we do, including the two most important: glutamate and GABA (gamma aminobutyric acid). They also utilize, as do we, acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, melatonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, levodopa, indole-3-acetic acid, 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, testosterone (and other androgens), estradiol (and other estrogens), nicotine, and a number of other neuroactive compounds. They also make use of their plant-specific neurotransmitter, auxin, which, like serotonin, for example, is synthesized from tryptophan. These plant intelligence transmitters are used, as they are in us, for communication within the plant organism and to enhance brain function.

The similarity of human and plant neural systems and the presence of identical chemical messengers within them illustrate just why the same molecular structures (e.g., morphine, coc aine, alcohol) that affect our neural nets also affect plant consciousness. Jagadis Bose, who developed some of the earliest work on plant neurobiology and plant intelligence in the early 1900s, treated plants with a wide variety of chemicals to see what would happen. In one instance, he covered large, mature trees with a tent, then chloroformed them. (The plants breathed in the chloroform through their stomata, just as they would normally breathe in air.) Once anesthetized, the trees could be uprooted and moved without going into shock—the pain perception of the plants diminished. He found that morphine had the same effects on plant consciousness as that of humans, reducing the plant pain perception and pulse proportionally to the dose given. Too much took the plant to the point of death, but the administration of atropine, as it would in humans, revived it. Alcohol, he found, did indeed get a plant drunk. It, as in us, induced a state of high excitation early on, but as intake progressed the plant began to get depressed, and with too much it passed out. The plant felt drunk.

Irrespective of the chemical he used, Bose found that the plant responded identically to the human; the chemicals had the same effect on the plant’s consciousness and nervous system as it did the human. ...

That excerpt says it better than I ever could and there are more details in the link. The findings show they can think and feel like we do, even to the point that if we give them anesthesia it will reduce the shock of being uprooted and re-potted. So, they feel pain and what sounds like, anxiety. They have their own "world wide web" underground through their root system. Using their roots to not only gather nutrients but also to connect with other plants and gain information on what is around them in the environment. Sometimes they use that information to change at a genetic level or adapt to newly introduced challenges. That is all done through collecting data. Which means they have to "think" about what is occurring.

Continued...

Intelligent Plants? Part 2

Gas plants produce a clear gas on humid, warm nights. This gas is said to be ignitable with a lit match.

They communicate using both their roots and chemicals released into the air. Reaching out and helping other plants in need by sharing nutrients/water with them. Plants will also combat invasive/dangerous species by using insects which, they can summon at will:

Scientists have known for the past two decades that many wild and agricultural plants launch an immune-like chemical defense when attacked by insects. That chemical resistance response can make the plant a poorer food for the insect and it may send out an aromatic SOS that hails the insect's natural enemies.

One of the tomato's common pests is the beet armyworm, a greenish 1-inch-long caterpillar that feeds on tomato leaves and fruit. Thaler was curious how effective the tomato plant's resistance response was in defending the plant by calling in the beet armyworm's natural enemy, a tiny parasitic wasp.

The chemical resistance response in a plant is technically known as the "octadecanoid pathway," a complex chemical chain-reaction that is triggered when an insect feeds on the plant. A wound from the insect signals the plant to produce a chemical known as "jasmonic acid," which in turn causes increased production of chemicals responsible for the leafy green odors of plants.

"Wasps can smell those compounds through their antennae and can more easily find the caterpillars when the caterpillars are less than 1 centimeter long," Thaler said. "The plants are essentially sending up a chemical 'smoke-signal' to attract the wasps." ...

That's pretty cool considering I sometimes can't even summon my dog back to the porch when he needs to come in. And if that doesn't show some type of intelligence, I don't know what would. But this could be a action/reaction type situation. I guess you can decide that for yourself. Although, I don't know any human who can summon an insect army at will...and we are supposed to be smart!

Plants know their siblings and won't compete with them for resources. Yep, they are kinder to their siblings then us humans are to ours. Which, considering they aren't able to just move out when things get tough, it makes perfect sense.

In a study of more than 3,000 mustard seedlings, scientists discovered that the young plants recognize their siblings — other plants grown from the seeds of the same momma plant — using chemical cues given off during root growth. And it turns out mustard plants won’t compete with their brethren the way they will with strangers: Instead of rapidly growing roots to suck up as much water and minerals as possible, plants who sensed nearby siblings developed a shallower root system and more intertwined leaves. ...

This is just a small sampling of information on how plants are intelligent. If I were to write about each sign of intelligence individually, this would be a 30 post or more thread with that information alone. Which would be ok I guess, but I'm not looking to do a full book here, just trying to do an overview of plants in general. So, we are gonna move on and I'll leave some links right here so you can read about it further if you wish...

Secret Life of Plants...231pg online pdf

Smarty Plants

What a Plant Knows...17pgs pdf

This is an hour long documentary titled: What a Plant Talks About

When we think about plants, we don't often associate a term like "behavior" with them, but experimental plant ecologist JC Cahill wants to change that. The University of Alberta professor maintains that plants do behave and lead anything but solitary and sedentary lives. What Plants Talk About teaches us all that plants are smarter and much more interactive than we thought!

Another hour long documentary called How Plants Communicate & Think.

Continued...

edit on 13-3-2018 by blend57 because: Always an Edit! :/

Death by Plant

The pitcher plant is among the largest of all pitchers and is so big that it can catch rats as well as insects in its leafy trap. ...

Yep, some plants are carnivorous just like us. Which I knew about the Venus fly trap, but I didn't know there were other plants that ate meat. There's a lot more evil doer plants then we realize (than I realized) though. I never thought I'd find so many different plants that are deadly. I'm leading off with a couple of mild ones, basically just cool special effects because, well, their cool...

Some plants bleed real blood! Ok, that was a lie too. They bleed a red colored resin that looks like blood when they get injured. But they do have cool names that imply they bleed blood such as Dragon's Blood Tree and The Bleeding Tooth Fungus:

It is not the texture of the bark, shape of the tree, or even the fact that it could live up to 500 years old, that makes the Dragon’s Blood Tree so famous though, it is the blood red sap that oozes out of it when it is cut.

Now you may be saying to yourself “trees don’t have circulatory systems and blood, what are you talking about trees bleeding?” and you would be partially right. Trees don't have blood cells or veins like animals, but they do have vascular systems made of xylem and phloem which carry nutrients and water throughout the plant. In sap bearing trees like D. Cinnabari , the carbohydrates transformed by the photosynthetic process are goopy and are transported through the xylem. Simply put the reasons why the sap is red is rooted in the nutrients taken in from the soil and air and the enzymes created because of those nutrients. ...

Scientifically known as hydnellum peckii, the young bleeding tooth fungus’s thick red fluid oozes through its tiny pores, creating the appearance of blood....

I've found an unusual amount of carnivorous plants. The pitcher plant, Venus flytrap, Cape Sundew, Rafflesia, Elephant-foot yam...I'm sure that isn't all of them as it is believed that there hundreds of carnivorous and thousands of poisonous plant species. Basically they are the "hunters" of the plant world. Only instead of tracking down and stalking their prey, they make the prey come to them.

Carnivorous plants come in all sizes and the largest ones. Some, shaped like giant pitchers with a lid covered with the plant’s sweet syrupy secretion, are found on the island of Borneo. They are so big, that they can hold two liters of water when filled to the brim, and were thought to catch rodents! But no rat or rat-like creature has ever been found inside one of these pitchers. Why then do they have these shapes and what is it for? Scientists studying these fascinating plants have recently come to a very strange conclusion.

These plants don’t catch rodents -- they eat their poop! And how do we know? Well, look at the evidence. These giant pitcher plants grow under certain trees. The size of the pitcher-lip matches the exact size of the tree shrew (small mammals that resemble squirrels) that lives on the trees. Yet, no shrew has ever been found inside the pitcher. ...

Ok, so not all of them eat meat. I lied again ... or did I? The picture says one thing, the video says another. Maybe what they eat is still up for debate or different species of the plant eat different things. But hey, I'm writing as I find the information! So, some plants (the pitcher plant specifically) just want to munch on animal feces (maybe). And some plants have very specific ways to trap and eat animals. I'm going with the video on this one and saying that pitcher plants do indeed eat meat. For me the explanation of how they trap and dissolve the animal slowly using enzymes makes sense.

I eventually found a plant that commits murder. Basically is sucks the life right out of it's "prey":

Several types of figs (Ficus spp.) are called "stranglers" because they grow on host trees, which they slowly choke to death.

Once established, the young strangler figs begin sending aerial roots down to the ground, where they quickly dive into the soil and anchor themselves. The roots may dangle from the host tree's canopy or creep down its trunk. Once in contact with the ground, the fig enters a growth spurt, plundering moisture and nutrients that the host tree needs. The strangler fig's roots encircle the host tree's roots, cutting off its supply of food and water, ultimately killing the host tree. Meanwhile, back at the epiphyte, the strangler fig is busy producing new leaves and shoots that soon become large enough to overshadow the host tree's foliage, stealing sunlight and rainfall from the host canopy. By the time the host tree is dead, the strangler fig is large and strong enough to stand on its own, usually encircling the lifeless, often hollow body of the host tree. ...

I can relate to the host tree. Many times I've felt like the life has been sucked right out of me after a day of work.

Those are some of the unusual ones. Most of us don't think about plants being anything but beautiful. No one believes that a flower would harm anything...but they do! Some even give off toxic, deadly poison if you touch or eat them:

Closely related to poison hemlock (the plant that famously killed Socrates), water hemlock has been deemed "the most violently toxic plant in North America." A large wildflower in the carrot family, water hemlock resembles Queen Anne’s lace and is sometimes confused with edible parsnips or celery. However, water hemlock is infused with deadly cicutoxin, especially in its roots, and will rapidly generate potentially fatal symptoms in anyone unlucky enough to eat it. Painful convulsions, abdominal cramps, nausea, and death are common, and those who survive are often afflicted with amnesia or lasting tremors.

Continued...

Recap

Before trees, Earth was home to fungi that grew 26 feet tall.

- Plants were on this Earth before we were

- They started out as algae and evolved to land plants

- They control the climate (or adapt because of climate, still up for debate)

- One of the major sources of modern medicine

- Angiosperms quick evolution is still a abominable mystery

- Plants can be deadly (like, seriously deadly) and some eat meat.

We took a quick look at the history of flowers, evolution, their impact on climate change, their medicinal history, and also their deadly side. Dived a little deeper into some subjects more than others, but that's where my reading took me, so, that's where I took the thread. All the web sites that I used are included with the quotes as well so I do not have any additional links to provide.

It was pretty interesting to read about and learn the bare basics. Some questions still left unanswered, and some of the information I knew but never really thought about in depth. I'm sure there are plenty of members who can add some more to this thread, and correct anything I got wrong. I would appreciate it if you would do so.

As always, thanks for reading and I hope you found something of value...

blend57

edit on 13-3-2018 by blend57 because: Always an Edit! :/

I like plants, I love the trees and woods and ferns. I like the wildflowers blooming in the fields. I just can't see people digging up the ground

and planting flowers that can mess up the ecosystem just to make things conform to their idea of beauty. A tree does not have to fit our idea of

beautiful to be beautiful.

I like dandelions, I like Yarrow. I like the little wild flowers and the black eyed susans and daisies that grow wild. I even like the flowers on the thistles and that fuzzy looking stalky light green plant that grows in my yard. I like the looks of the bees on the burdock flowers. I like the clovers. I see people cursing the natural things around here and kill them in their yards only to plant flowers that they think are beautiful. Plants that can turn invasive to the environment here sometimes.

I forgot, great thread, we evolved with plants, we cannot live without them on this planet.

I like dandelions, I like Yarrow. I like the little wild flowers and the black eyed susans and daisies that grow wild. I even like the flowers on the thistles and that fuzzy looking stalky light green plant that grows in my yard. I like the looks of the bees on the burdock flowers. I like the clovers. I see people cursing the natural things around here and kill them in their yards only to plant flowers that they think are beautiful. Plants that can turn invasive to the environment here sometimes.

I forgot, great thread, we evolved with plants, we cannot live without them on this planet.

edit on 13-3-2018 by rickymouse because: (no reason

given)

a reply to: blend57

Interesting article, as usual, Blend

I discovered some 'volunteer' crocus in the yard a few days ago and snapped some photos. They were s o pretty and delicate. We are in another cold snap with some snow a day ago and I've not checked on them to see if they survived. Oddly enough, the daffodils have and typically when the weather is like this after they bloom, they quickly wilt and turn brown and go away until next year.

If one pays attention, you can see old house places (that the foundation may be gone now) and where someone likely planted them along the driveway or porch area many years ago. They still thrive against all odds!

Anyway, I shall pay more attention to the plants in general especially the angiosperms!

Interesting article, as usual, Blend

I discovered some 'volunteer' crocus in the yard a few days ago and snapped some photos. They were s o pretty and delicate. We are in another cold snap with some snow a day ago and I've not checked on them to see if they survived. Oddly enough, the daffodils have and typically when the weather is like this after they bloom, they quickly wilt and turn brown and go away until next year.

If one pays attention, you can see old house places (that the foundation may be gone now) and where someone likely planted them along the driveway or porch area many years ago. They still thrive against all odds!

Anyway, I shall pay more attention to the plants in general especially the angiosperms!

a reply to: blend57

Willow is amazing, if you take willow branches and soak it in water, that water will help other newly planted plants root better.

I am a long time gardener and I grow from seed, and also purchase a lot of plants.

Last year I purchased some very expensive over the top plants. I was shocked and offended by friends that questioned me on how much I spent on them, when they wouldn't bat an eyelash on spending the same amount on eating out, their clothing shoes etc. I simply say plants bring me great joy and you can't put a price on that and smile.

I planted a wildflower garden late one year. It was right around 5 pm and I was admiring the flowers, and a swarm of what seemed like a million dragonflies circled around me. Not one single one hit me, but they buzzed around for a good thirty minutes. It was one of those moments that will stay with me forever, the sound, the way the sun was shining from the west, the flowers, the smell. It almost seems as if they were thanking me for my plantings and doing a little dance.

Willow is amazing, if you take willow branches and soak it in water, that water will help other newly planted plants root better.

I am a long time gardener and I grow from seed, and also purchase a lot of plants.

Last year I purchased some very expensive over the top plants. I was shocked and offended by friends that questioned me on how much I spent on them, when they wouldn't bat an eyelash on spending the same amount on eating out, their clothing shoes etc. I simply say plants bring me great joy and you can't put a price on that and smile.

I planted a wildflower garden late one year. It was right around 5 pm and I was admiring the flowers, and a swarm of what seemed like a million dragonflies circled around me. Not one single one hit me, but they buzzed around for a good thirty minutes. It was one of those moments that will stay with me forever, the sound, the way the sun was shining from the west, the flowers, the smell. It almost seems as if they were thanking me for my plantings and doing a little dance.

Wow Blend! One of the most fascinating threads I've read in a while! I will return to re-read some things and watch those videos.

I always wonder how vegetarians feel after discovering that plants have feelings.

Thank you for an amazing thread and the work you put into this presentation!

I always wonder how vegetarians feel after discovering that plants have feelings.

Thank you for an amazing thread and the work you put into this presentation!

a reply to: blend57

Great thread Blendsy!

As far as angiosperms' rapid spread: have seen forest areas after a fire, where blueberry bushes just move-in, and take-over massive acreage of land, within a couple of years. They seem to spread quicker than any kind of grass or weed.

Other than that: well just hug a tree, and have flowery day!

Great thread Blendsy!

As far as angiosperms' rapid spread: have seen forest areas after a fire, where blueberry bushes just move-in, and take-over massive acreage of land, within a couple of years. They seem to spread quicker than any kind of grass or weed.

Other than that: well just hug a tree, and have flowery day!

edit on 13-3-2018 by Nothin because: sp

a reply to: purplemer, Nothin, Night Star, JAGStorm,

TNMockingbird, rickymouse

Thanks to all of you who commented and also those that didn't but read the thread! I really didn't think that a post about plants would attract much interest but I'm grateful to all of you and appreciate your input/thoughts!

Heading out of town for a few days so I wanted to comment before I went!

Thanks again!

blend

Thanks to all of you who commented and also those that didn't but read the thread! I really didn't think that a post about plants would attract much interest but I'm grateful to all of you and appreciate your input/thoughts!

Heading out of town for a few days so I wanted to comment before I went!

Thanks again!

blend

new topics

-

The Baloney aka BS Detection Kit

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 3 hours ago -

Suspected Iranian agent working for Pentagon while U.S. coordinated defense of Israel

US Political Madness: 3 hours ago -

How does my computer know

Education and Media: 6 hours ago -

USO 10 miles west of caladesi island, Clearwater beach Florida

Aliens and UFOs: 10 hours ago

top topics

-

USO 10 miles west of caladesi island, Clearwater beach Florida

Aliens and UFOs: 10 hours ago, 8 flags -

Suspected Iranian agent working for Pentagon while U.S. coordinated defense of Israel

US Political Madness: 3 hours ago, 5 flags -

How does my computer know

Education and Media: 6 hours ago, 2 flags -

The Baloney aka BS Detection Kit

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 3 hours ago, 1 flags

active topics

-

White clots found in 20% of dead bodies after covid vaccine

Medical Issues & Conspiracies • 41 • : Kurokage -

The Baloney aka BS Detection Kit

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 3 • : mysterioustranger -

Nakedeye Mother of Dragons Comet Is Here!

Space Exploration • 3 • : SchrodingersRat -

US and Israel Reportedly Conclude Most Hostages Still Held in Gaza Are Dead

War On Terrorism • 146 • : Ohanka -

How does my computer know

Education and Media • 10 • : Scratchpost -

Negotiations and Diplomacy.

History • 13 • : Kurokage -

Brave Russians say NO to 'vote Vlad'

Breaking Alternative News • 121 • : Kurokage -

It has begun... Iran begins attack on Israel, launches tons of drones towards the country

World War Three • 629 • : SchrodingersRat -

Suspected Iranian agent working for Pentagon while U.S. coordinated defense of Israel

US Political Madness • 6 • : CarlLaFong -

Candidate TRUMP Now Has Crazy Judge JUAN MERCHAN After Him - The Stormy Daniels Hush-Money Case.

Political Conspiracies • 191 • : SchrodingersRat

26