It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

6

share:

It has been an obsession of mine of late (and conceivably, for the rest of my life) to figure out the nuances and subtleties that underlie our vast

and complex evolution into our current mind and body.

A few things stick out, but the main thing is, how did we get this feeling we all have in us, of a need, so essential as to be banal, yet radical in it's reality:

Read this not as a mere statement, but as a iron-clad law of our human biology: we are forced by genes to self-organize in pursuit of other peoples positive regard for us. We do this mostly unconsciously, as what enters our perception in our actions towards the world are like the tip of an ice-berg, just visible enough for consciousness to make meaning of the interaction, but not so visible so that consciousness can bear witness to it's own obsequious longings.

In less pretentious sounding terms, our brain's have evolved a dissociative function that separates negative experiences of self from consciousness, which is itself made up by distributed networks throughout the cortex.

The logic is enormously plausible, and perhaps it has been so difficult to see is due to a lack of scientific evidence. However, with brain science and a maturing understanding of human evolution, it is becoming more and more apparent that human beings are enormously sensitive social animals who defend themselves non-consciously in the most elaborate sorts of ways.

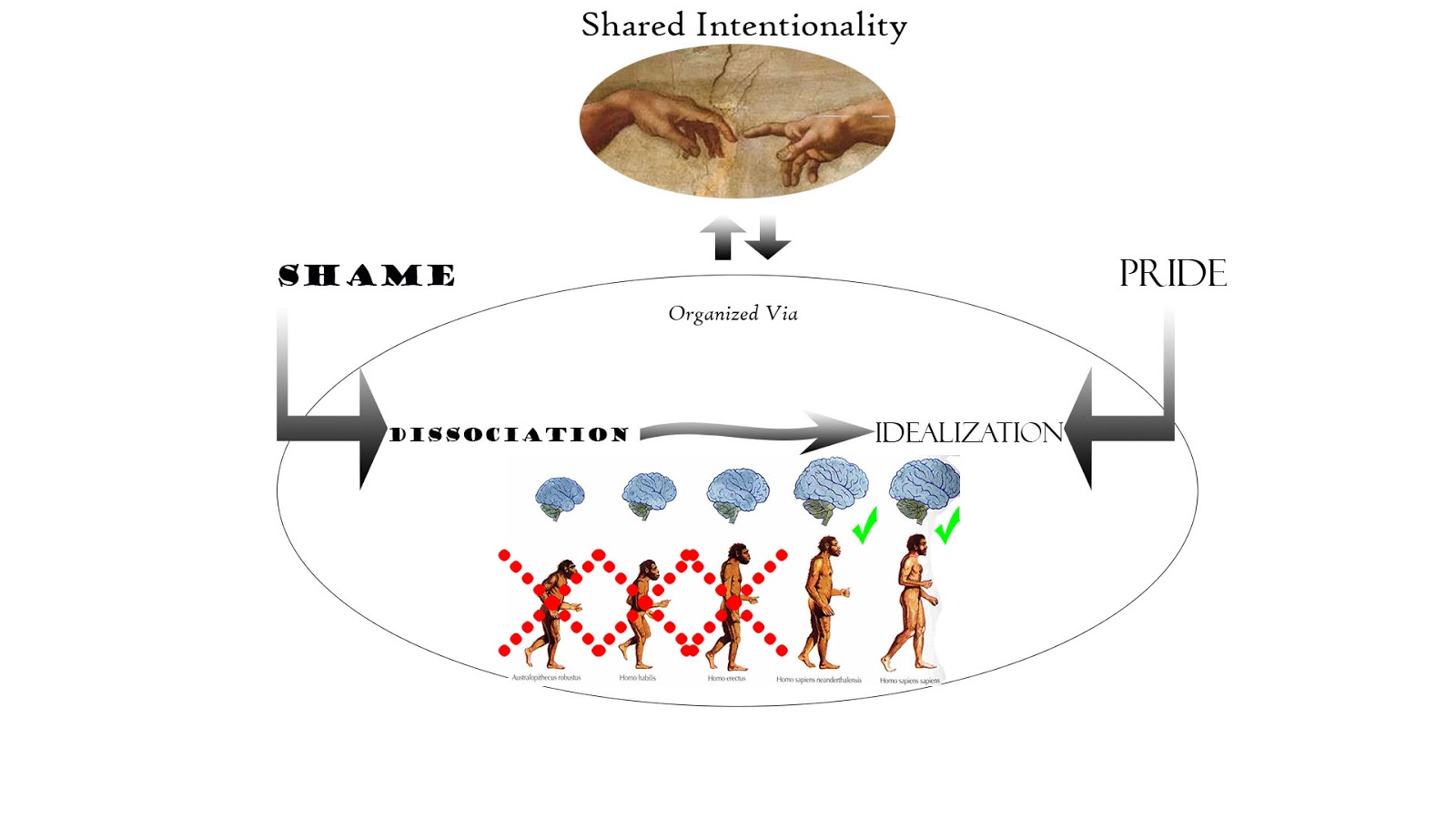

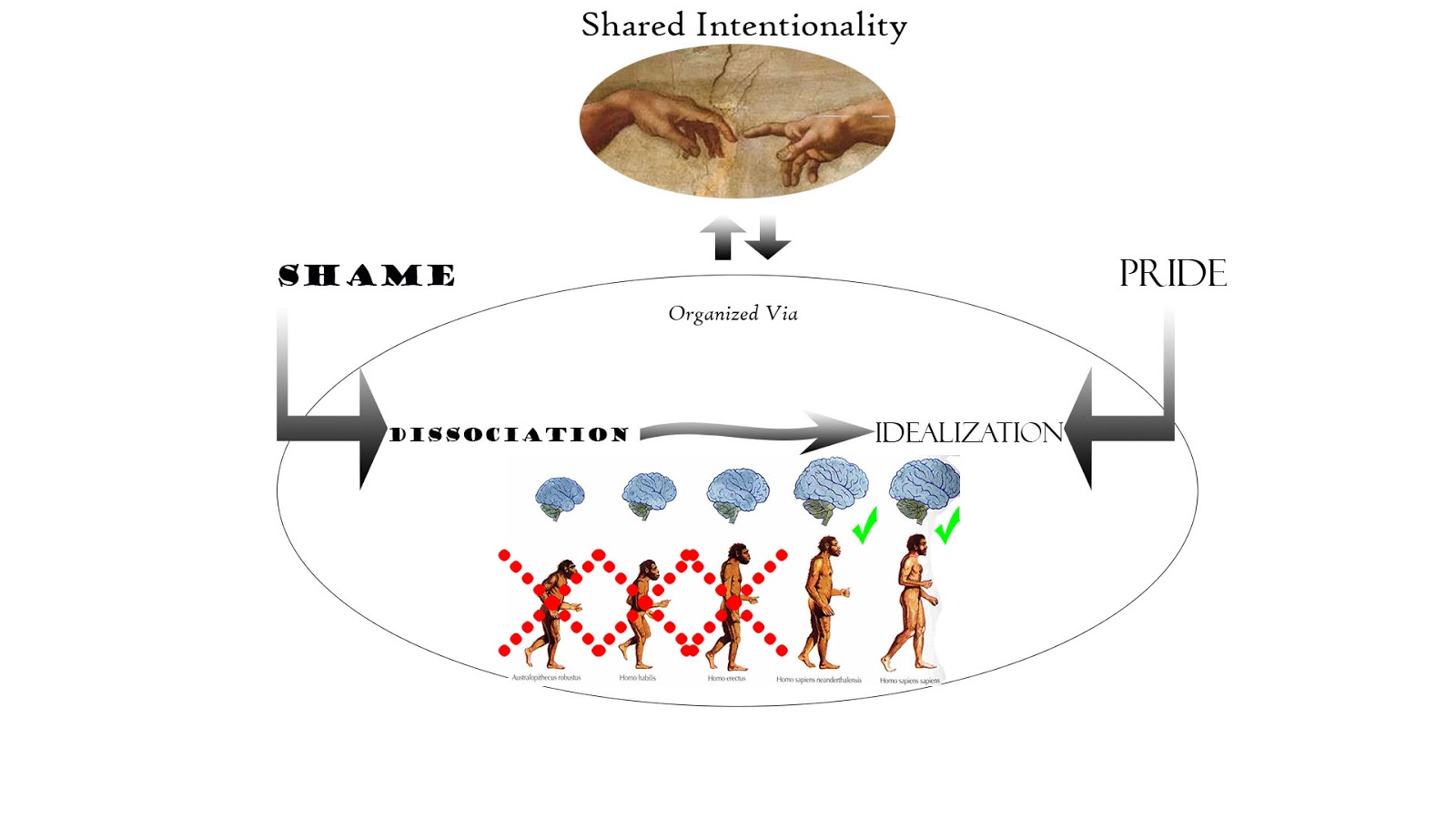

Figure 1 explains the overall logic of this dynamic:

Shared intentionality, as a concept, emerged out of the work of the developmental psychologist Michael Tomasellos experiments with chimpanzees at the Max Plank Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Between Chimps and Humans, Tomasello observed a fundamental difference in motivation. While Chimps were aware of one another, obviously, they did not seem to have an innate motivation to act in altruistic, other-concerned ways. He reasoned that this absence in motivation derives from the fact that chimps are highly aggressive, hierarchical, patriarchal, creatures who seem to dominate one another more often than not. Humans, on the other hand, seem to be fundamentally motivated to seek social stimulation, and to care that the response that they get be a 'good' one - meaning a facial expression, gesture, and vocal tone, that expresses enthusiasm, and an unconscious affirmation of the other's "personhood". Although chimps, and really, all other social creatures can be said to be concerned about getting positive feedback, a humans concern is clothed in thought and language. Furthermore, a humans motivation itself implies something about it's ontological organization: we are 'focused', as it were, by the beam of light emanating from the group dynamic process that etched itself in our brains. Tomasello's theory doesn't merely explain how shared-intentionality provides a theory of 'group selection'. It literally explains how our minds became able to think in abstract, object-oriented way. The other, the heart of our interest, has always been the existence and presence of other minds. A facial expression, a goofy look, the cries of suffering, a lustful gaze - stuff like this, the very stuff we do, from moment to moment, was the 'grist' material that supported the growth of our brains.

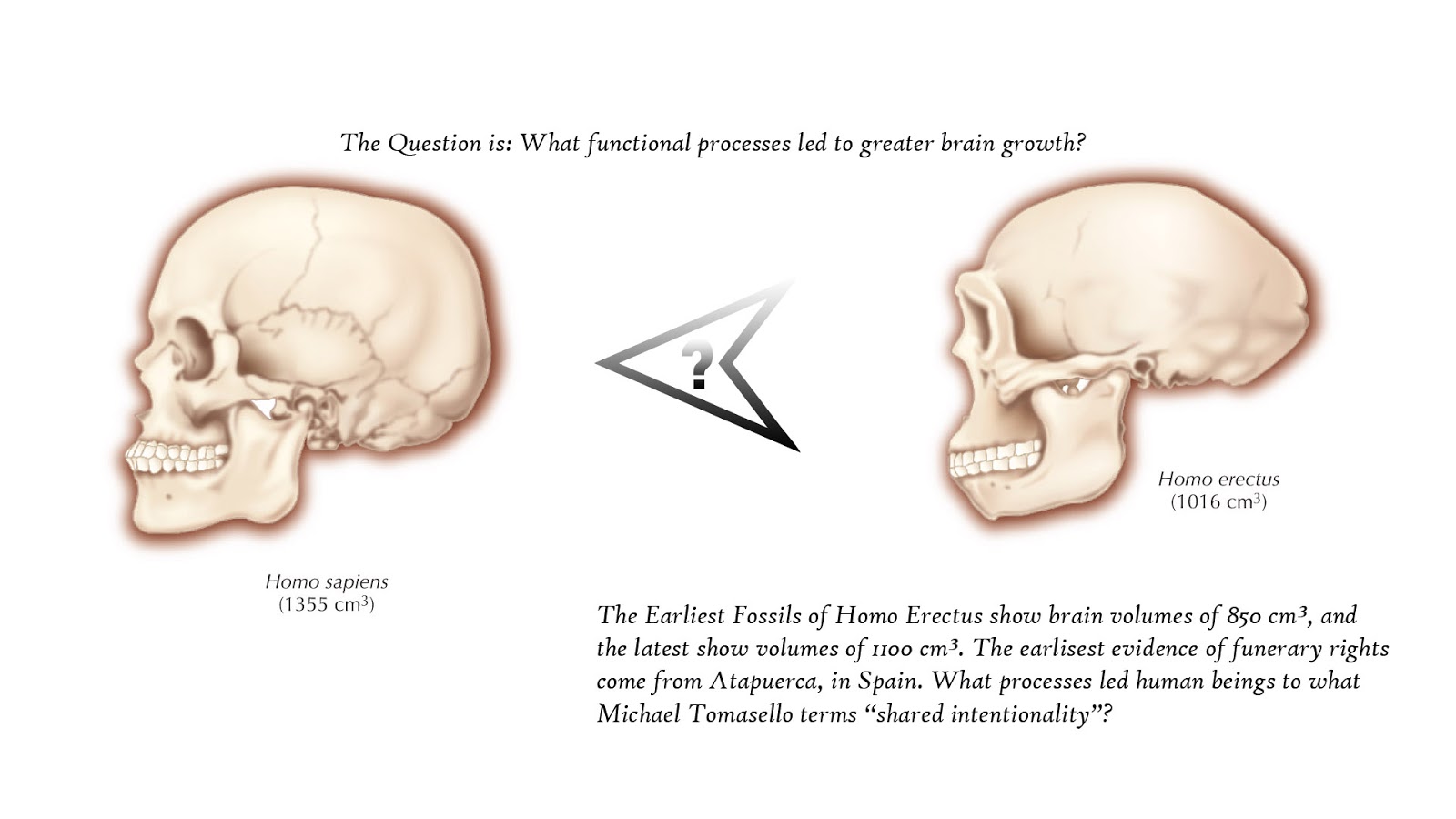

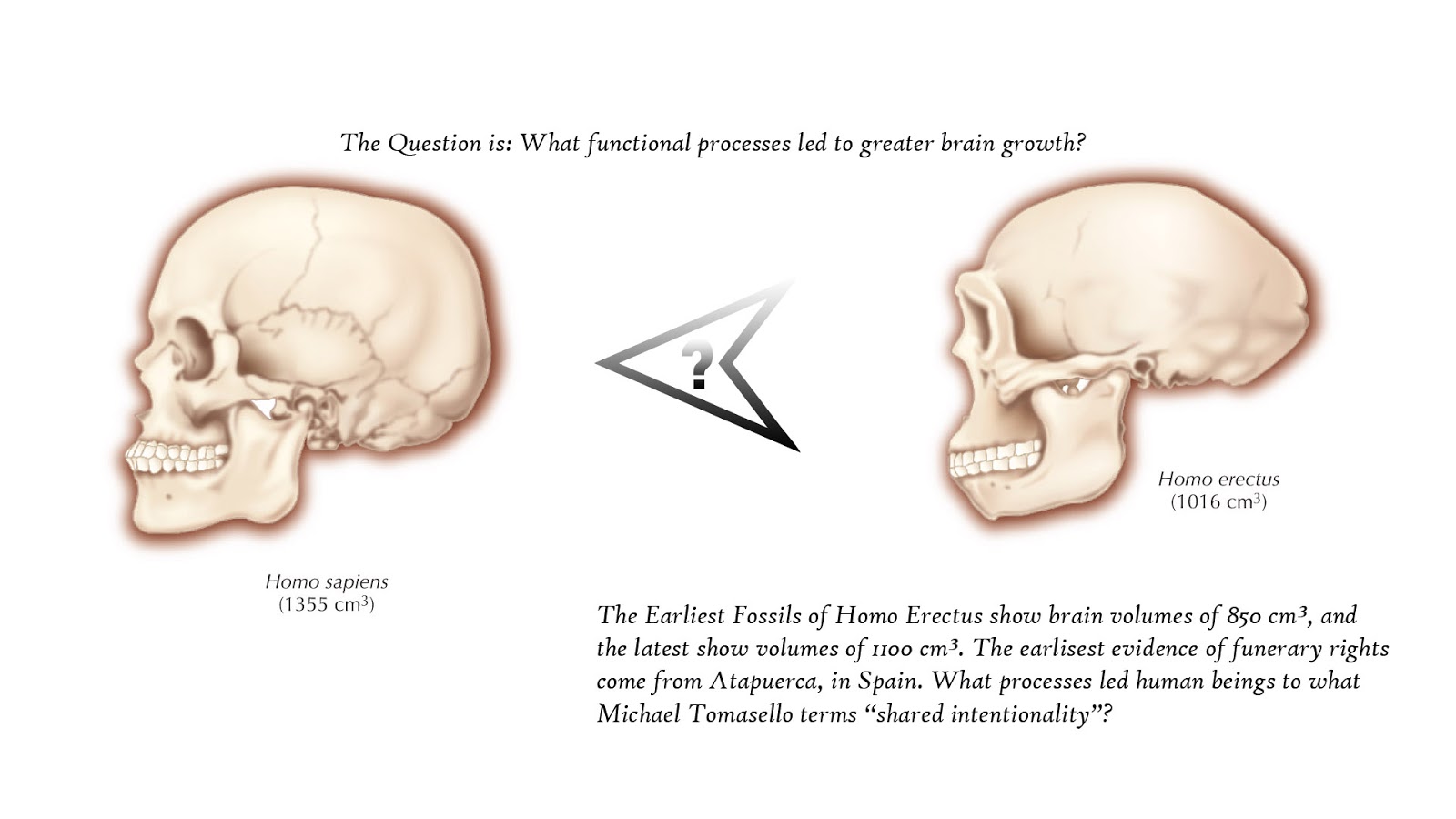

The mystery in between these two brains is the creature known to us as Homo Heidelbergensis - named so because the fossil was found in a town in Germany, and named after the university of Heidelberg.

It was this creature that went on to produce Homo Neanderthalensis, and, as more people are beginning to accept, Homo Sapiens. It was with this species that human motivation was fundamentally transformed, from being mostly organized in hierarchical, defence/threat oriented societies, typical of chimpanzees, to "horizontal", nurturing societies, with widespread allo-parenting, an unconscious cultivation of empathy, along with a growing fascination with thought, perception and experience, leading to the intuitive zeal of myth-making, philosophizing, and "transforming" the affects produced by life, into reflections writ large into the meaning of the universe.

It was this species who evolved into those earlier humans known as cro-magnon (40,000 ya). Yet the oddest thing is, our brains have gotten smaller since then. The most probably explanation has to do with the emergence of agriculture 10,000 years ago. If this is the case, than the human beings living 50, or even a 150 thousands years ago, may have possessed a similar epistemological and psychological toolkit as we do.

The evolution of our species over the last 200,000 years is not a "positive" science, as we can only recreate the past with reference to what we know in the present. However, with all that we currently know about the emergence of life, the notion that shame-pride, via dissociation and idealization mechanisms, serve the purpose of shared-intentionality' - a group-selection logic - we can see that each of these ideas ultimately revolve around the subject of "thermodynamic equilibrium". The whole universe is ultimately bounded by the 2 laws of thermodynamics. When life emerged, it was shown that chemicals could come together and maintain whats called "autopoeisis", or a self-stabilizing system. Evolution continued chugging forward, increasing in complexity about 700 million years ago with eukaryotes and endless "eternal ephemera", forms of multicellular assemblages that took on a macroscopic identity of wholeness. But throughout this process, the larger "mass" of the organism was always being guided and determined by thermodynamic equilibrium between interacting parts.

So too in us humans. If we merely acknowledge what motivates us, we will recognize what is necessary in order to "manage" our messy interior. If I care what you think about me, I acknowledge my sensitivity to negative reactions - what we could put into the "shame" side of the ledger. Shame is such a basic reaction that people have evolved scripts, narratives and cultures that 'build around' its stultifying reality. While it may help maintain self-esteem, it also encourages unnecessary and aggressive behaviors. Since our brain is a biophysically closed, yet psychologically "open" system, anything that comes "in" doesn't just magically disappear into the ether. If we've ever been charged or affected, or been subjected to long periods of negative emotions (particularly shame), our unconscious "self-system", or the motivation circuitry of the brain, will guide consciousness towards percepts that promote well being - a friendly delusion, perhaps - but a major problem when we recognize the way not-acknowledging a core vulnerability in our organization can create.

The brain - and the meanings within it - are always in dynamic interaction. When we exist, from moment to moment, our existence is in unconscious connection with the environment around it. Consciousness is an exquisitely small thing relative to the amount of information from the environment are brain 'picks up', and then proceeds to guide conscious processes by biasing feeling states and activating perceptual frames.

A few things stick out, but the main thing is, how did we get this feeling we all have in us, of a need, so essential as to be banal, yet radical in it's reality:

We all want others to like us

Read this not as a mere statement, but as a iron-clad law of our human biology: we are forced by genes to self-organize in pursuit of other peoples positive regard for us. We do this mostly unconsciously, as what enters our perception in our actions towards the world are like the tip of an ice-berg, just visible enough for consciousness to make meaning of the interaction, but not so visible so that consciousness can bear witness to it's own obsequious longings.

In less pretentious sounding terms, our brain's have evolved a dissociative function that separates negative experiences of self from consciousness, which is itself made up by distributed networks throughout the cortex.

The logic is enormously plausible, and perhaps it has been so difficult to see is due to a lack of scientific evidence. However, with brain science and a maturing understanding of human evolution, it is becoming more and more apparent that human beings are enormously sensitive social animals who defend themselves non-consciously in the most elaborate sorts of ways.

Figure 1 explains the overall logic of this dynamic:

Shared intentionality, as a concept, emerged out of the work of the developmental psychologist Michael Tomasellos experiments with chimpanzees at the Max Plank Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Between Chimps and Humans, Tomasello observed a fundamental difference in motivation. While Chimps were aware of one another, obviously, they did not seem to have an innate motivation to act in altruistic, other-concerned ways. He reasoned that this absence in motivation derives from the fact that chimps are highly aggressive, hierarchical, patriarchal, creatures who seem to dominate one another more often than not. Humans, on the other hand, seem to be fundamentally motivated to seek social stimulation, and to care that the response that they get be a 'good' one - meaning a facial expression, gesture, and vocal tone, that expresses enthusiasm, and an unconscious affirmation of the other's "personhood". Although chimps, and really, all other social creatures can be said to be concerned about getting positive feedback, a humans concern is clothed in thought and language. Furthermore, a humans motivation itself implies something about it's ontological organization: we are 'focused', as it were, by the beam of light emanating from the group dynamic process that etched itself in our brains. Tomasello's theory doesn't merely explain how shared-intentionality provides a theory of 'group selection'. It literally explains how our minds became able to think in abstract, object-oriented way. The other, the heart of our interest, has always been the existence and presence of other minds. A facial expression, a goofy look, the cries of suffering, a lustful gaze - stuff like this, the very stuff we do, from moment to moment, was the 'grist' material that supported the growth of our brains.

The mystery in between these two brains is the creature known to us as Homo Heidelbergensis - named so because the fossil was found in a town in Germany, and named after the university of Heidelberg.

It was this creature that went on to produce Homo Neanderthalensis, and, as more people are beginning to accept, Homo Sapiens. It was with this species that human motivation was fundamentally transformed, from being mostly organized in hierarchical, defence/threat oriented societies, typical of chimpanzees, to "horizontal", nurturing societies, with widespread allo-parenting, an unconscious cultivation of empathy, along with a growing fascination with thought, perception and experience, leading to the intuitive zeal of myth-making, philosophizing, and "transforming" the affects produced by life, into reflections writ large into the meaning of the universe.

It was this species who evolved into those earlier humans known as cro-magnon (40,000 ya). Yet the oddest thing is, our brains have gotten smaller since then. The most probably explanation has to do with the emergence of agriculture 10,000 years ago. If this is the case, than the human beings living 50, or even a 150 thousands years ago, may have possessed a similar epistemological and psychological toolkit as we do.

The evolution of our species over the last 200,000 years is not a "positive" science, as we can only recreate the past with reference to what we know in the present. However, with all that we currently know about the emergence of life, the notion that shame-pride, via dissociation and idealization mechanisms, serve the purpose of shared-intentionality' - a group-selection logic - we can see that each of these ideas ultimately revolve around the subject of "thermodynamic equilibrium". The whole universe is ultimately bounded by the 2 laws of thermodynamics. When life emerged, it was shown that chemicals could come together and maintain whats called "autopoeisis", or a self-stabilizing system. Evolution continued chugging forward, increasing in complexity about 700 million years ago with eukaryotes and endless "eternal ephemera", forms of multicellular assemblages that took on a macroscopic identity of wholeness. But throughout this process, the larger "mass" of the organism was always being guided and determined by thermodynamic equilibrium between interacting parts.

So too in us humans. If we merely acknowledge what motivates us, we will recognize what is necessary in order to "manage" our messy interior. If I care what you think about me, I acknowledge my sensitivity to negative reactions - what we could put into the "shame" side of the ledger. Shame is such a basic reaction that people have evolved scripts, narratives and cultures that 'build around' its stultifying reality. While it may help maintain self-esteem, it also encourages unnecessary and aggressive behaviors. Since our brain is a biophysically closed, yet psychologically "open" system, anything that comes "in" doesn't just magically disappear into the ether. If we've ever been charged or affected, or been subjected to long periods of negative emotions (particularly shame), our unconscious "self-system", or the motivation circuitry of the brain, will guide consciousness towards percepts that promote well being - a friendly delusion, perhaps - but a major problem when we recognize the way not-acknowledging a core vulnerability in our organization can create.

The brain - and the meanings within it - are always in dynamic interaction. When we exist, from moment to moment, our existence is in unconscious connection with the environment around it. Consciousness is an exquisitely small thing relative to the amount of information from the environment are brain 'picks up', and then proceeds to guide conscious processes by biasing feeling states and activating perceptual frames.

edit on 12-12-2015

by Astrocyte because: (no reason given)

edit on 12-12-2015 by Astrocyte because: (no reason given)

new topics

-

Is the origin for the Eye of Horus the pineal gland?

General Conspiracies: 56 minutes ago -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News: 1 hours ago -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

2024 Elections: 1 hours ago -

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness: 1 hours ago -

Sheetz facing racial discrimination lawsuit for considering criminal history in hiring

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 1 hours ago -

In an Historic First, In N Out Burger Permanently Closes a Location

Mainstream News: 3 hours ago -

MH370 Again....

Disaster Conspiracies: 4 hours ago -

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 6 hours ago -

Chronological time line of open source information

History: 7 hours ago -

A man of the people

Diseases and Pandemics: 9 hours ago

6