It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

18

share:

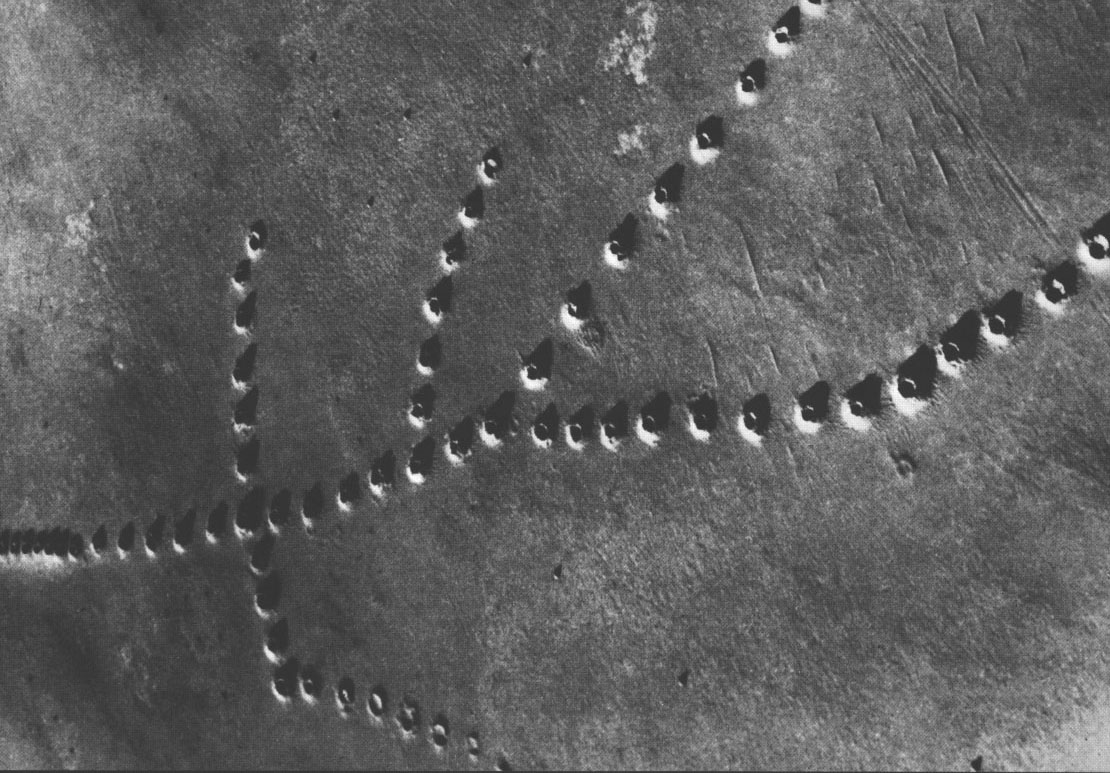

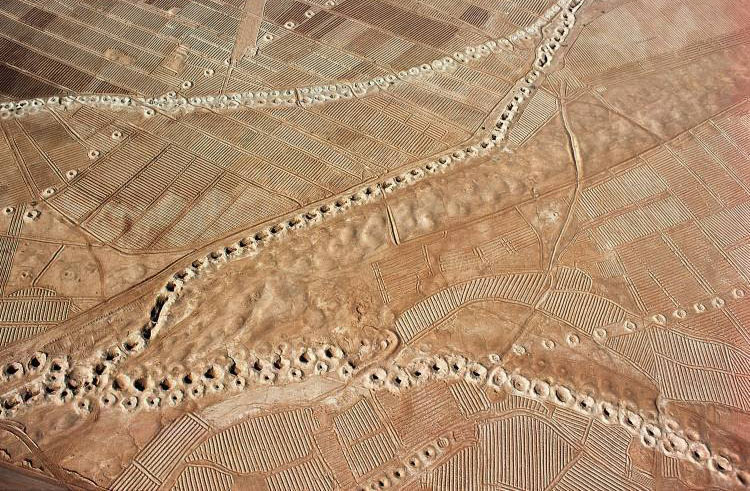

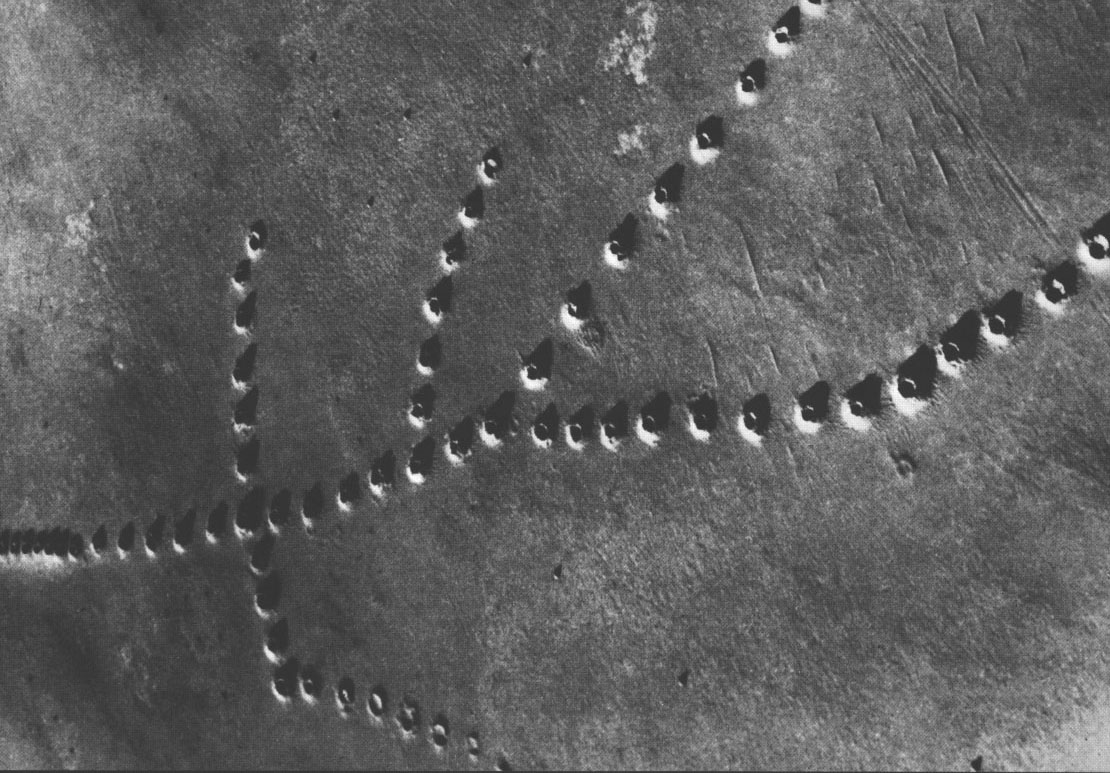

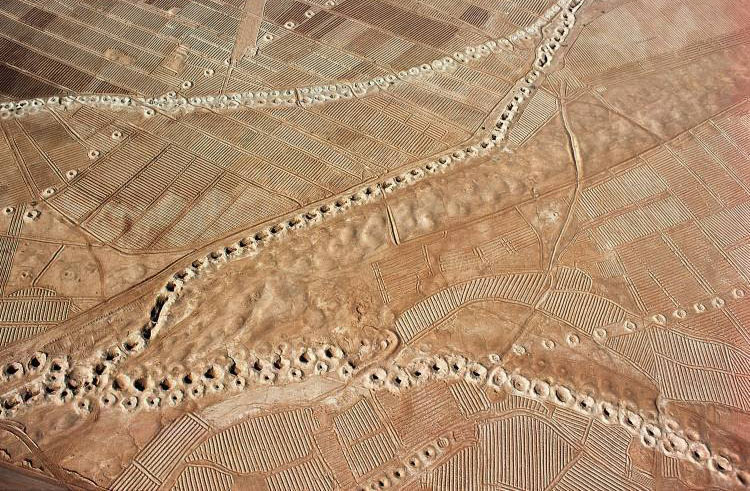

Best viewed from the air, like great scaled dragons curious markings stretch across the sands, in this example in the vicinity of Fars in Iran,

examples of an ancient technology that is still practised in some regions.

When one looks at these perhaps one sees some similarity to ancient lines composed of a linear series of pits from the Nazca region, and perhpas one should, becuase they would have shared similar concerns.

There are examples found in numerous locations in Iran, as well as regions such as Uzbekistan and kazakhstan, at least some of the recent arial photos from that region of curious markings relate to them.

In Iranian they are known as Khariz, in the Arabic Qanat, they are concerned with sourcing supplies of underground water.

This would appear to be the very God of such...

All very sensible, i'm not sure however what role the geoglyphs seen in the first example play, whether they had a symbolic or ritual function in association with the underground water management system, they don't look like practical irrigation channels, which of course can often be seen in conjunction.

Kariz

When one looks at these perhaps one sees some similarity to ancient lines composed of a linear series of pits from the Nazca region, and perhpas one should, becuase they would have shared similar concerns.

There are examples found in numerous locations in Iran, as well as regions such as Uzbekistan and kazakhstan, at least some of the recent arial photos from that region of curious markings relate to them.

In Iranian they are known as Khariz, in the Arabic Qanat, they are concerned with sourcing supplies of underground water.

This would appear to be the very God of such...

The technology of kārēz exploits a difference in grade between a tunnel and the groundwater table. The grade of the tunnel is less steep than the grade of the water table, so that the tunnel ends at an elevation distinctly higher than that of the water table.

In a few exceptional cases, the channels are quite long. The known maximum lengths are some 50 km in the region of Yazdand about 35 kilometers at Gonābād in Khorasan

The channel is the essential functional element of the kārēz, but vertical shafts, which connect the tunnel to the surface, are needed for digging the tunnels and play no role in the actual operation of the kārēz. The vertical shafts are laid out at more or less regular intervals, which are relatively close in order to facilitate the removal of debris.

All very sensible, i'm not sure however what role the geoglyphs seen in the first example play, whether they had a symbolic or ritual function in association with the underground water management system, they don't look like practical irrigation channels, which of course can often be seen in conjunction.

Kariz

a reply to: Kantzveldt

Aboriginal Songlines.

"One of the most unique, a fusion of navigation and oral mythological storytelling, originated among the indigenous peoples of Australia, who navigated their way across the land using paths called songlines or dreaming tracks." (from Google search result precis)

Aboriginal Songlines.

"One of the most unique, a fusion of navigation and oral mythological storytelling, originated among the indigenous peoples of Australia, who navigated their way across the land using paths called songlines or dreaming tracks." (from Google search result precis)

a reply to: Revolution9

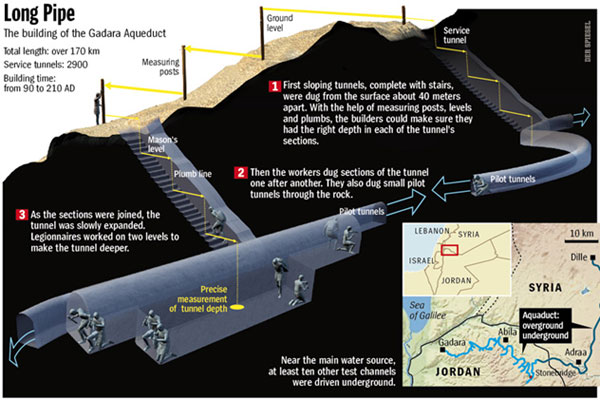

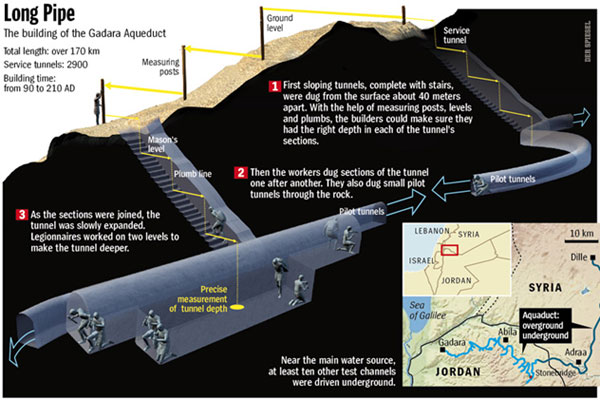

It's really the case with these that everything important is beneath the ground, the markings are only service entrance holes, the greatest constructed was by the Romans;

It's really the case with these that everything important is beneath the ground, the markings are only service entrance holes, the greatest constructed was by the Romans;

Qanats tap into subterranean water in a manner that efficiently delivers large quantities of water to the surface without need for pumping. The water drains by gravity, with the destination lower than the source, which is typically an upland aquifer. Qanats allow water to be transported over long distances in hot dry climates without loss of much of the water to evaporation.

It is very common in the construction of a qanat for the water source to be found below ground at the foot of a range of foothills of mountains, where the water table is closest to the surface. From this point, the slope of the qanat is maintained closer to level than the surface above, until the water finally flows out of the qanat above ground. To reach an aquifer, qanats must often extend for long distances

Although the Arabic name ‘Qanat Firaun’ means ‘Canal of the Pharaohs’, the massive canal was not Egyptian but Imperial Roman, and stands as a testament to their incredible engineering abilities. The 170-kilometre pipeline is not only the world’s longest underground aqueduct of the antiquity, it is also the most complex, and represents a colossal work of hydroengineering.

Qanat Firaun

The 'geoglyphs' in the first picture are irrigated fields, with the irrigation channels following the local topography.

a reply to: Astyanax

Yes they appear as shallow channels but they don't seem the traditional linear arrangement or particularly rational, there can be seen similar patterns at Firuzabad which may be symbolic pattern.

Sometimes there seems the creation of pattern in laying out the course of the Qanat and the above ground marks as in the recent example from Kazakhstan;

So i think it's important to recognize above ground features associated with sophisticated hydro-engineering, and to what extent that carries through with regards to the likes of the Nazca to whose culture the Kazakhstan geoglyphs have been readily compared.

Yes they appear as shallow channels but they don't seem the traditional linear arrangement or particularly rational, there can be seen similar patterns at Firuzabad which may be symbolic pattern.

Sometimes there seems the creation of pattern in laying out the course of the Qanat and the above ground marks as in the recent example from Kazakhstan;

So i think it's important to recognize above ground features associated with sophisticated hydro-engineering, and to what extent that carries through with regards to the likes of the Nazca to whose culture the Kazakhstan geoglyphs have been readily compared.

a reply to: Butterfinger

At face value they look quite similar, but it depends if there's an aquifer beneath, otherwise it would have to be the case that they were imitating the above ground features of a system without actually digging it out...

At face value they look quite similar, but it depends if there's an aquifer beneath, otherwise it would have to be the case that they were imitating the above ground features of a system without actually digging it out...

a reply to: Kantzveldt

That's because they follow the rises and depressions in the land, which is bumpy. Sometimes the channeling gets quite intricate — and ingenious. I've seen similar arrangements up in the Mustang valley of Nepal, around Jomsom and Marpha.

Those are not marks in the ground, they are access shafts. The Qanats of Iran

they don't seem the traditional linear arrangement or particularly rational

That's because they follow the rises and depressions in the land, which is bumpy. Sometimes the channeling gets quite intricate — and ingenious. I've seen similar arrangements up in the Mustang valley of Nepal, around Jomsom and Marpha.

Sometimes there seems the creation of pattern in laying out the course of the Qanat and the above ground marks as in the recent example from Kazakhstan.

Those are not marks in the ground, they are access shafts. The Qanats of Iran

edit on 2/11/15 by Astyanax because: of a typo.

new topics

-

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 1 hours ago -

Chronological time line of open source information

History: 3 hours ago -

A man of the people

Diseases and Pandemics: 4 hours ago -

Ramblings on DNA, blood, and Spirit.

Philosophy and Metaphysics: 4 hours ago -

4 plans of US elites to defeat Russia

New World Order: 6 hours ago -

Thousands Of Young Ukrainian Men Trying To Flee The Country To Avoid Conscription And The War

Other Current Events: 9 hours ago

top topics

-

Israeli Missile Strikes in Iran, Explosions in Syria + Iraq

World War Three: 13 hours ago, 17 flags -

Iran launches Retalliation Strike 4.18.24

World War Three: 12 hours ago, 6 flags -

Thousands Of Young Ukrainian Men Trying To Flee The Country To Avoid Conscription And The War

Other Current Events: 9 hours ago, 6 flags -

12 jurors selected in Trump criminal trial

US Political Madness: 12 hours ago, 4 flags -

4 plans of US elites to defeat Russia

New World Order: 6 hours ago, 2 flags -

A man of the people

Diseases and Pandemics: 4 hours ago, 2 flags -

Chronological time line of open source information

History: 3 hours ago, 2 flags -

Ramblings on DNA, blood, and Spirit.

Philosophy and Metaphysics: 4 hours ago, 1 flags -

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 1 hours ago, 1 flags

active topics

-

Israeli Missile Strikes in Iran, Explosions in Syria + Iraq

World War Three • 69 • : YourFaceAgain -

4 plans of US elites to defeat Russia

New World Order • 26 • : WaESN -

ChatGPT Beatles songs about covid and masks

Science & Technology • 22 • : iaylyan -

The Acronym Game .. Pt.3

General Chit Chat • 7730 • : RAY1990 -

Biden--My Uncle Was Eaten By Cannibals

US Political Madness • 51 • : YourFaceAgain -

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology • 8 • : RAY1990 -

Thousands Of Young Ukrainian Men Trying To Flee The Country To Avoid Conscription And The War

Other Current Events • 12 • : ScarletDarkness -

So I saw about 30 UFOs in formation last night.

Aliens and UFOs • 33 • : Encia22 -

Two Serious Crimes Committed by President JOE BIDEN that are Easy to Impeach Him For.

US Political Madness • 18 • : xuenchen -

12 jurors selected in Trump criminal trial

US Political Madness • 34 • : Vermilion

18