It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

share:

originally posted by: galadofwarthethird

a reply to: jeep3r

Ah! It happens, I dont see why people make such a big deal about a bunch of stones, the similarities may be inherited, but its also there because it just happens to work

To some people it's just a bunch of stones, to me the details of the stonework are remarkable and not so easy to interpret. Even Flinders Petrie had difficulties with that regarding the stone cutting techniques in AE culture.

When considering said similarities (which IMO are not self-explanatory), we should keep our mind open for a potential link, even if any generally accepted 'hard evidence' has yet to be found.

edit on 7-6-2014 by jeep3r because: text

On the surface, based solely on visual imagery, I suppose it is easy to make a leap of logic and assume these two cultures must somehow be

connected because of similarities in stone working or religious motifs.

But expand the horizons to other cultures, and you'll see these similarities exist worldwide because we, human beings, think alike.

Those trapezoidal indentations in stone blocks used to structurally connect two blocks together? Not only do they exist as shown here in ancient Egypt and Peru, but also in ancient Angkor Wat, ancient Greece, all of the ancient Near East, ancient Briton, Turkey, even ancient Carnac (in France). Similar problem, similar solution.

The stone work in constructing the multifaceted walls (examples at Cuzco, Sacsayhuaman, Easter Island, Valley Temple in Giza) however are the ones that throw people the most. Stop for one minute and dwell on how they had to build them, and you begin to see how similarities arise even though the these cultures are separated not only by oceans and thousands of miles, but thousands of years as well.

First: lack of precision tools. Egypt had crude levels (plumb bobs), Peru had none. In modern times we take for granted in building a stone wall that every course will be plumb and level. Each new course needs the course below it to be level. We use mortar to make micro-adjustments to keep each block level and plumb, and course spacing uniform. If a block wall gets even slightly out of plumb or level, it's ability to remain standing is seriously degraded.

So how did the ancients overcome a lack of precision making tools, and non-uniform building materials?

#1: By scribing each block perfectly to it's neighboring block. A painstaking process, but one that assures a perfect fit between the two blocks, no matter how out of level of plumb they are. You can see in the walls in Peru, the initial course is haphazard, none of the first course of blocks are plumb or level. But they didn't need to be. The ancient builders would rely on scribing to assure the wall was stable, rather than the impossible task (for them) of keeping each course perfectly plumb and level. Not until the Egyptians advanced enough in the times of the 3rd/4th Dynasty did they eschew scribing and canting wall in favor of level and uniform courses of stone block. (even though they would retain sloping walls as a design motif).

#2: By canting the wall - as seen in a multitude of cultures, from Sumer (inward sloping mud-brick buttress walls) to Egypt (which had contact with Sumer), beginning with inward sloping mud-brick buttress walls to inward sloping stone walls in the first stone-built pyramids). China, Susa, and virtually every ancient world capital had some form of block wall construction relying on a canted form for structural integrity.

For the ancients, the first walls were certainly built of found rock, and stacked. Bigger rocks equal bigger and more stable walls, but there begins the inherent instability of bigger walls that lack precision joinery. So we see bigger rocks, scribed to precisely fit. Place the rock near it's final resting place, hold it in place with blocking, scribe it, chip away at it until it fits exactly. Since each rock is non-uniform in size, you end up with multiple facets, but that it a good thing, lacking mortar it helps lock each block in place. If needed, chip out a trapezoid shape in two neighboring blocks and pour in a soft metal to act as a key. To lift the blocks, rope is needed, but what do you attach it to? Solution - a "coin" or "boss," a protrusion of stone left in two of the face of the block around which the rope can be lashed. Once a block is in place, the face can be finished to remove the boss. This was evident in all the ancient cultures.

Again, similar problems, similar solutions.

But expand the horizons to other cultures, and you'll see these similarities exist worldwide because we, human beings, think alike.

Those trapezoidal indentations in stone blocks used to structurally connect two blocks together? Not only do they exist as shown here in ancient Egypt and Peru, but also in ancient Angkor Wat, ancient Greece, all of the ancient Near East, ancient Briton, Turkey, even ancient Carnac (in France). Similar problem, similar solution.

The stone work in constructing the multifaceted walls (examples at Cuzco, Sacsayhuaman, Easter Island, Valley Temple in Giza) however are the ones that throw people the most. Stop for one minute and dwell on how they had to build them, and you begin to see how similarities arise even though the these cultures are separated not only by oceans and thousands of miles, but thousands of years as well.

First: lack of precision tools. Egypt had crude levels (plumb bobs), Peru had none. In modern times we take for granted in building a stone wall that every course will be plumb and level. Each new course needs the course below it to be level. We use mortar to make micro-adjustments to keep each block level and plumb, and course spacing uniform. If a block wall gets even slightly out of plumb or level, it's ability to remain standing is seriously degraded.

So how did the ancients overcome a lack of precision making tools, and non-uniform building materials?

#1: By scribing each block perfectly to it's neighboring block. A painstaking process, but one that assures a perfect fit between the two blocks, no matter how out of level of plumb they are. You can see in the walls in Peru, the initial course is haphazard, none of the first course of blocks are plumb or level. But they didn't need to be. The ancient builders would rely on scribing to assure the wall was stable, rather than the impossible task (for them) of keeping each course perfectly plumb and level. Not until the Egyptians advanced enough in the times of the 3rd/4th Dynasty did they eschew scribing and canting wall in favor of level and uniform courses of stone block. (even though they would retain sloping walls as a design motif).

#2: By canting the wall - as seen in a multitude of cultures, from Sumer (inward sloping mud-brick buttress walls) to Egypt (which had contact with Sumer), beginning with inward sloping mud-brick buttress walls to inward sloping stone walls in the first stone-built pyramids). China, Susa, and virtually every ancient world capital had some form of block wall construction relying on a canted form for structural integrity.

For the ancients, the first walls were certainly built of found rock, and stacked. Bigger rocks equal bigger and more stable walls, but there begins the inherent instability of bigger walls that lack precision joinery. So we see bigger rocks, scribed to precisely fit. Place the rock near it's final resting place, hold it in place with blocking, scribe it, chip away at it until it fits exactly. Since each rock is non-uniform in size, you end up with multiple facets, but that it a good thing, lacking mortar it helps lock each block in place. If needed, chip out a trapezoid shape in two neighboring blocks and pour in a soft metal to act as a key. To lift the blocks, rope is needed, but what do you attach it to? Solution - a "coin" or "boss," a protrusion of stone left in two of the face of the block around which the rope can be lashed. Once a block is in place, the face can be finished to remove the boss. This was evident in all the ancient cultures.

Again, similar problems, similar solutions.

I cannot believe that primitive humans were able to shape rock like that. There's much we don't know, or it has been kept from us. Some of these

stones have what looks like tool marks on them. I'd like to see one person, right now, quarry a stone of these sizes, cut them with that precision

with primitive tools. It would take a looong time just to do one. Not to mention who taught them this technology. Their biggest goal of the day

should've been getting food to survive, NOT building things like these with such precision. Hardly something that hungry folk could do! Even by

todays standards or tools.

originally posted by: Fylgje

I cannot believe that primitive humans were able to shape rock like that. There's much we don't know, or it has been kept from us. Some of these stones have what looks like tool marks on them. I'd like to see one person, right now, quarry a stone of these sizes, cut them with that precision with primitive tools. It would take a looong time just to do one. Not to mention who taught them this technology. Their biggest goal of the day should've been getting food to survive, NOT building things like these with such precision. Hardly something that hungry folk could do! Even by todays standards or tools.

The Egyptians left a fair amount of half hacked out stones, broken stones and dumped stones halfway from quarry to site, plus records of how the pyramids were built (complete with bitching about pay from the builders), there are even illustrations with oxen pulling stele and pouring water into sand to making moving the blocks easier. It's not as hard to build these huge constructions as you'd think, it just involves a lot of sweat and fairly basic tools. The Egyptians had a lot of spare food to pay builders with, the Nile was one of the most fertile areas on Earth.

I keep wondering just where people get the idea they didn't build them from. They did keep records of construction projects for admin purposes and some of the papyrii for this still exist.

originally posted by: Antigod

originally posted by: Logarock

originally posted by: Antigod

originally posted by: PonderingSceptic

a reply to: Antigod

There may be no evidence connecting the two cultures. It doesn't mean there were no trade routes or outright direct exchange of crafts, goods. It did happen numerous times in history and similar events numerous times were made accepted historical facts. My guess is that there's no need to list them.

There's a question how there cannot be a connection, as there was constant contact through Inuit–Yupik cultures where rare artifacts and goods could have traveled through Asia. Ethnology has interesting myths from them. There also could have been contacts in other areas and this cannot be excluded.

Well, the Egyptians were appalling sailors, and didn't consider the world worth exploring. They hardly even moved around the Med, their ships were just not up to transatlantic travel. Egyptian tech and culture can be traced back every step to local Med and Nile cultures, so I can't see any far distant input. I did a LOT of research into the origin of Egyptian culture, from DNA to tech and the archaeology. It's all very obviously an evolution in situ. You see small underground tombs changing into Mastabas and small step pyramids, the writing evolve from simple pictograms in the pre dynastic era, copper working arriving from the Levant. Nothing is 'odd'. Under the farming layers of dirt there's a few thousand years of a simple mesolithic ceramic culture then nothing but and stone tools right back to homo habilis.

Sure you did a LOT of research on the origin of Egyptian culture. Serious researchers understand that Narmer, the Scorpion line was right out of Mesopotamia. Mesopotamian influence is strong and always a part of Egypt's development.

The original farming cultures came from the very northern part of Mesopotamia, the headwaters area. That's about as far as any connection to Mesopotamia goes.

Narmer AKA Menes was a local king, probably upper Egyptian not Mesopotamian. You'd know this if you read RECENT work on the unification of Egypt in the early dynasties. The whole concept of the founding of Egypt's dynasty as a Mesopotamian is incorrect and called 'the dynastic race theory' which was discarded in the last century.

en.wikipedia.org...

This theory had strong supporters in the Egyptological community in the first half of the 20th century, but has since lost mainstream support.

I'm lucky because I know people with phd's in Egyptology that I can check this with.

The pharaohs were of local stock as can be seen when you examine their bones and DNA. They have rather differently shaped heads and faces to Mesopotamians. Long necks, tend to be long in the midface region, sometimes elongated and often round back to their skulls (think like a Somalian for this). A large minority input from Black Africans from the Nile region is typical in all upper Egyptians remains. These people had nothing to do biologically with Mesopotamia.

In Egyptology maybe like no were else one thing you cant count on is that the experts don't agree and there are many of them.

Pharaohs and DNA.....I am talking 1st dynasty for which there is no DNA. And anyone knows many of the dynasties were not related by blood. And one of the worst things you can do with Egyptian history and archeology is make it an African thing.

As far as Mesopotamia and a 1st Egyptian dynasty connection one can find the Scorpion icon, royal icon in a good number of the Mesopotamian cylinder seals. Egypt's first dynasty unification effort under the Scorpion kings most notably Narmer was a colonization/unification effort.

originally posted by: Antigod

a reply to: Harte

Sorry, I didn't post the c14 dates from the hearths and a stone tool find going back to 40-50k bp in America, I didn't get that number from Luzia. I could have made that clear. I'll dig up the articles if you want.

Please do. It would certainly add to the thread.

Are you talking about the Topper site? No actual hearth there and the carbon found can be explained by a wildfire.

Harte

originally posted by: Logarock

As far as Mesopotamia and a 1st Egyptian dynasty connection one can find the Scorpion icon, royal icon in a good number of the Mesopotamian cylinder seals. Egypt's first dynasty unification effort under the Scorpion kings most notably Narmer was a colonization/unification effort.

The Narmer palette indicates a union of upper and lower Egypt. This union was celebrated throughout the rest of Ancient Egyptian history through iconography and the royal titularies, among other ways.

As far as Mesopotamia, the main indicators of influence from there are construction methods. There's no doubt that the two civilizations were in close (for those days) contact.

The appearance of Egyptian iconography in Mesopotamia is not an indicator of origins. Look at it this way - the "winged disk" icon originated in Egypt, but was utilized throughout Mesopotamia across all the civilizations that arose there.

Harte

a reply to: Harte

I personally believe the winged disk came out of Mesopotamia.

Narmers name icon on the platte is that of the mud brick builders. A catfish and chisel. Its Mesopotamian, delta, "mud cat".

Below is the dynastic family icon...Scorpion...right out of one of the Mesopotamian city sates lines.

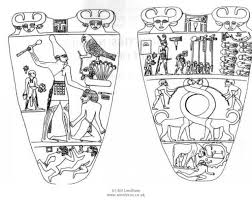

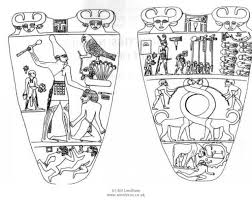

Below....The uplifted scepter a Hercules/Orion icon, Horus with hook in nose, captive king taken by the forelocks, the intertwined beasts, the bull...ect....all right out of Sumer.

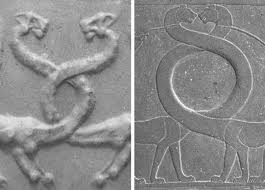

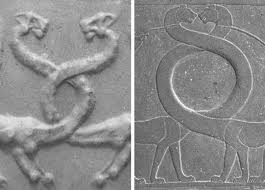

Compare above to below....Uruk 3000 bc..Also note the presents of "Horus".

Close up comparison.

I personally believe the winged disk came out of Mesopotamia.

Narmers name icon on the platte is that of the mud brick builders. A catfish and chisel. Its Mesopotamian, delta, "mud cat".

Below is the dynastic family icon...Scorpion...right out of one of the Mesopotamian city sates lines.

Below....The uplifted scepter a Hercules/Orion icon, Horus with hook in nose, captive king taken by the forelocks, the intertwined beasts, the bull...ect....all right out of Sumer.

Compare above to below....Uruk 3000 bc..Also note the presents of "Horus".

Close up comparison.

edit on 8-6-2014 by Logarock because: n

originally posted by: Blackmarketeer

So how did the ancients overcome a lack of precision making tools, and non-uniform building materials?

#1: By scribing each block perfectly to it's neighboring block. A painstaking process (...)

That's quite an understatement. Especially given the obvious lack of data regarding duration, manpower and precision that would be needed when using traditional stone cutting techniques to manufacture such blocks, let alone structures & buildings. I dare to say it's impossible to achieve that kind of result without the help of alternative techniques.

To lift the blocks, rope is needed, but what do you attach it to? Solution - a "coin" or "boss," a protrusion of stone left in two of the face of the block around which the rope can be lashed

Do you think they carved away the whole front face of the stone just to leave the protusions? That's IMO not the true explanation for what we see. Apart from that, some stones have those 'knobs', others don't. And yet others have indention marks or both (independent of size, by the way). Honestly, it seems like we need an entirely different story to account for all that.

Place the rock near it's final resting place, hold it in place with blocking, scribe it, chip away at it until it fits exactly.

If the result would actually look as if it were 'scribed' then I could agree. But that's doubtful: instead we see indications of heat, vitrification and an overall homogeneous stone surface that looks like andesite, but is probably reconstituted & recrystallized siliceous limestone with just very little fossil residue inside.

Also, take a look at the convex, pillow-shaped outline of the stones as well as the seamless concave jointing. All this strongly suggests that the pre-incan stone masons applied an entirely different method to shape the blocks.

Again, similar problems, similar solutions.

Don't you think that's too easy an answer considering that J.P. Protzen didn't even come close to replicating a tiny miniature block with the same features?

originally posted by: Logarock

a reply to: Harte

I personally believe the winged disk came out of Mesopotamia.

You can, of course, "believe" anything you want. You could be right. Nobody knows.

But the fact is, the earliest winged disk icon found to this point came from Egypt.

In a similar vein, I could say I "believe" the iconography you point out in your post originated in Egypt.

I don't believe this, but the claim has as much legitimacy as yours.

Harte

a reply to: jeep3r

Yes - that's exactly what they did. This isn't even an issue for debate, as it's fact. Greeks were especially adept at this method, but it had it's drawbacks, as ropes could still slip from the boss. I'm sure there were plenty of disasters when a block tumbled free of it's lashings and crushed an ancient worker or two.

Romans improved in this by carving out "Lewis" holes (named for their discoverer), a trapezoidal hole wider at the bottom than the top. Three plates of iron were then inserted, two flared ends and a middle spacer. Once inserted and held in place by a bolt, the plates would be impossible to remove until disassembled. Then to remove the holes, the entire face of the block would be 'abraded,', taken down to the depth of the holes.

Do Lewis holes, coins, and bosses waste material and create additional work? Absolutely. But that was what they had to do, to move large blocks. Labor costs were cheap back then.

Do you think they carved away the whole front face of the stone just to leave the protusions? That's IMO not the true explanation for what we see. Apart from that, some stones have those 'knobs', others don't. And yet others have indention marks or both (independent of size, by the way). Honestly, it seems like we need an entirely different story to account for all that.

Yes - that's exactly what they did. This isn't even an issue for debate, as it's fact. Greeks were especially adept at this method, but it had it's drawbacks, as ropes could still slip from the boss. I'm sure there were plenty of disasters when a block tumbled free of it's lashings and crushed an ancient worker or two.

Romans improved in this by carving out "Lewis" holes (named for their discoverer), a trapezoidal hole wider at the bottom than the top. Three plates of iron were then inserted, two flared ends and a middle spacer. Once inserted and held in place by a bolt, the plates would be impossible to remove until disassembled. Then to remove the holes, the entire face of the block would be 'abraded,', taken down to the depth of the holes.

Do Lewis holes, coins, and bosses waste material and create additional work? Absolutely. But that was what they had to do, to move large blocks. Labor costs were cheap back then.

a reply to: Blackmarketeer

There are no indications of chipping or chiseling the front face down to the bosses on this wall (bottom section, click for large version). Also, one can make out a continuous & homogeneous surface texture without interuption:

Again, no scrapemarks in the hi-res image here. Instead, the overall surface texture is undisturbed from top to bottom. Further, how do you see the scribing and chiseling technique applied to bocks around corners?

Lastly, how do you go about chiseling & chipping in order to achieve an extremely polished & precise 'finish' on those concave joints?

I don't think time, manpower and traditional techniques can account for what we see. And if you look closely at the walls at Sacsayhuamán, Ollantaytamboo and other related sites, the indentions, protuberances and surface textures strongly suggest that the material was 'soft' before taking the final shape we see today.

There are no indications of chipping or chiseling the front face down to the bosses on this wall (bottom section, click for large version). Also, one can make out a continuous & homogeneous surface texture without interuption:

Again, no scrapemarks in the hi-res image here. Instead, the overall surface texture is undisturbed from top to bottom. Further, how do you see the scribing and chiseling technique applied to bocks around corners?

Lastly, how do you go about chiseling & chipping in order to achieve an extremely polished & precise 'finish' on those concave joints?

I don't think time, manpower and traditional techniques can account for what we see. And if you look closely at the walls at Sacsayhuamán, Ollantaytamboo and other related sites, the indentions, protuberances and surface textures strongly suggest that the material was 'soft' before taking the final shape we see today.

edit on 9-6-2014 by jeep3r because: text

a reply to: jeep3r

Chipping and chiseling rough fits the block, abrading fine tunes it and leaves a smooth surface.

There was a PBS program that featured a video of one archeologist showing how blocks could be fitted together by scribing. It wasn't nearly as labor intensive as you make it out to be.

Chipping and chiseling rough fits the block, abrading fine tunes it and leaves a smooth surface.

There was a PBS program that featured a video of one archeologist showing how blocks could be fitted together by scribing. It wasn't nearly as labor intensive as you make it out to be.

a reply to: Blackmarketeer

This is worth watching and listening too, it plays well into this thread.

www.youtube.com...

www.youtube.com...

This is worth watching and listening too, it plays well into this thread.

www.youtube.com...

www.youtube.com...

edit on 11-6-2014 by LABTECH767 because: (no reason given)

Right. Toss out five and a half hours of woo vid.

I don't have enough Cheetohs for that.

Harte

I don't have enough Cheetohs for that.

Harte

a reply to: Harte

Well hart I see you have a lot in common with Edward John Smith, you are so cock sure that you are correct you can not be bothered to slow down and do not care what you are heading toward, still at least you enjoyed the video weather you saw the ice berg or not.

Well hart I see you have a lot in common with Edward John Smith, you are so cock sure that you are correct you can not be bothered to slow down and do not care what you are heading toward, still at least you enjoyed the video weather you saw the ice berg or not.

a reply to: LABTECH767

Is your premise so immensely complicated that you must refer us to almost 6 hours - half of it D.H. Childress - in order to get the point across?

Please. You know I didn't waste my morning on Childress.

Say what you think yourself. Childress won't even respond in his own forum.

Harte

Is your premise so immensely complicated that you must refer us to almost 6 hours - half of it D.H. Childress - in order to get the point across?

Please. You know I didn't waste my morning on Childress.

Say what you think yourself. Childress won't even respond in his own forum.

Harte

a reply to: jeep3r

a reply to: LABTECH767

Several other things to consider that may change your opinion on Inca stone work, and that these were the product of the Inca and not some ancient super civilization (or other advanced races):

Inca stone masons were so highly prized that Spanish Conquistadors sought them out, and had them continue building in stone for them - and several walls come from the colonial period using the same multifaceted fitting. In fact these colonial era walls often get mislabeled on fringe sites.

Example:

Photo: Colonial-era Cusco wall, "carved stones and snake."

In 1987 Vincent R. Lee, an architect, proposed the Inca fit their stone blocks using a known method of scribing and coping. He demonstrated this method in a 1995 NOVA program titled "Inca." In this program, he suspends a stone block above the spot it will be scribed to, using wood blocking (logs, shims, etc.). The block will already be squared up roughly along the edge, the face will be finished. Now he begins to use the scribe, which can be made out of any material. A wooden triangle, always held at the same angle (or held plumb with the aid of a plumb bob). So long as the scribe is held at the same angle and remains the same spacing, it can trace the outline of one stone onto the face of the other. The backside is not scribed, it just needs to be shaped roughly to provide some backcut. After scribing and chipping the stone with finer and finer cuts, a simple abrading block 'sands' the block to the scribe line. Then the block is lowered into position to test it for fit. The process is repeated until the fit is perfect. In the video, a couple modern masons recreated the effect and only spent about 4 hours getting a large block to fit with a high degree of precision. One can expect the ancient Inca who were talented in scribing and coping masonry were highly prized.

Regarding the bosses seen on some blocks in the cyclopean walls, Lee suggests these bosses were used to allow prop logs to be placed underneath to support the stone during the scribing process (he demonstrated this). Since these larger blocks would have to be scribed perfectly on the first try due to their size, it should be noted these bosses are found only on the larger stone blocks. Mind you, when propping blocks up for scribing, they aren't freestanding, rather they are propped in place along the wall and against previously set blocks. They are only suspended a few inches above their final resting place. The scribe is a small handheld tool, much like it is in modern times.

The counterpoint to bosses are these notches, where again support logs could be placed to prop a block up while it is being scribed. These seem much safer than the bosses:

To further bolster the scribing and coping method, stone blocks were also fitted into niches in living rock. Obviously, no 'melting' was involved here.

Here is a link to the "Inca" NOVA page, sadly I don't see the program itself online anywhere. They do have some text and a Q/A on their page. You'll just have to catch it on PBS, I've seen it several times now as part of their "Lost Empires" series.

NOVA "Inca," Questions and Answers

One question/answer in particular seems to dispense with the notion that these carefully fitted stones were "melted" into place. I won't touch the fact that much of the stone work there is made of sedimentary rock and not igneous, so it would never in fact "melt," and would instead spall/crumble or become quicklime and several gasses (see Can limestone melt?).

So behind the carefully fitted vertical edge on some blocks researchers have noted that the block face will 'taper away,' which would be practical convenience. Modern masons and carpenters would call this a 'backcut,' as it makes it easier to shape to fit only a sliver of that face along it's exposed edge, rather than the entire depth of a face. How much to taper a face or 'backcut' it doesn't matter since it will never be seen - whatever is convenient for the mason.

Vincent R. Lee's web page

Hope this helps.

a reply to: LABTECH767

Several other things to consider that may change your opinion on Inca stone work, and that these were the product of the Inca and not some ancient super civilization (or other advanced races):

Inca stone masons were so highly prized that Spanish Conquistadors sought them out, and had them continue building in stone for them - and several walls come from the colonial period using the same multifaceted fitting. In fact these colonial era walls often get mislabeled on fringe sites.

Example:

Photo: Colonial-era Cusco wall, "carved stones and snake."

In 1987 Vincent R. Lee, an architect, proposed the Inca fit their stone blocks using a known method of scribing and coping. He demonstrated this method in a 1995 NOVA program titled "Inca." In this program, he suspends a stone block above the spot it will be scribed to, using wood blocking (logs, shims, etc.). The block will already be squared up roughly along the edge, the face will be finished. Now he begins to use the scribe, which can be made out of any material. A wooden triangle, always held at the same angle (or held plumb with the aid of a plumb bob). So long as the scribe is held at the same angle and remains the same spacing, it can trace the outline of one stone onto the face of the other. The backside is not scribed, it just needs to be shaped roughly to provide some backcut. After scribing and chipping the stone with finer and finer cuts, a simple abrading block 'sands' the block to the scribe line. Then the block is lowered into position to test it for fit. The process is repeated until the fit is perfect. In the video, a couple modern masons recreated the effect and only spent about 4 hours getting a large block to fit with a high degree of precision. One can expect the ancient Inca who were talented in scribing and coping masonry were highly prized.

Regarding the bosses seen on some blocks in the cyclopean walls, Lee suggests these bosses were used to allow prop logs to be placed underneath to support the stone during the scribing process (he demonstrated this). Since these larger blocks would have to be scribed perfectly on the first try due to their size, it should be noted these bosses are found only on the larger stone blocks. Mind you, when propping blocks up for scribing, they aren't freestanding, rather they are propped in place along the wall and against previously set blocks. They are only suspended a few inches above their final resting place. The scribe is a small handheld tool, much like it is in modern times.

The counterpoint to bosses are these notches, where again support logs could be placed to prop a block up while it is being scribed. These seem much safer than the bosses:

To further bolster the scribing and coping method, stone blocks were also fitted into niches in living rock. Obviously, no 'melting' was involved here.

Here is a link to the "Inca" NOVA page, sadly I don't see the program itself online anywhere. They do have some text and a Q/A on their page. You'll just have to catch it on PBS, I've seen it several times now as part of their "Lost Empires" series.

NOVA "Inca," Questions and Answers

One question/answer in particular seems to dispense with the notion that these carefully fitted stones were "melted" into place. I won't touch the fact that much of the stone work there is made of sedimentary rock and not igneous, so it would never in fact "melt," and would instead spall/crumble or become quicklime and several gasses (see Can limestone melt?).

Question: Do the blocks need to fit perfectly throughout or just along the edge? Is there any evidence that they were less careful nearer to the center of the blocks? ~Leon

Answer: This is similar to an earlier question, and the answer is that in many cases the rocks are perfectly fitted throughout their entire depth across both their horizontal bedding faces and their vertical rising faces. But in some instances we find what the questioner suggests, that only the horizontal bedding face is fitted perfectly for the future depth of the rock and the vertical rising face is fitted perfectly only at the visible edge, and behind that the rocks simply taper away from one another and loose fill is placed there to stabilize the rock in its position.

So behind the carefully fitted vertical edge on some blocks researchers have noted that the block face will 'taper away,' which would be practical convenience. Modern masons and carpenters would call this a 'backcut,' as it makes it easier to shape to fit only a sliver of that face along it's exposed edge, rather than the entire depth of a face. How much to taper a face or 'backcut' it doesn't matter since it will never be seen - whatever is convenient for the mason.

Vincent R. Lee's web page

Hope this helps.

edit on 11-6-2014 by Blackmarketeer because: (no reason given)

a reply to: Blackmarketeer

Your effort in researching mainstream explanations for the construction of these walls is remarkable and that's indeed appreciated. But just as you are not convinced that alternative methods may have been used, I am equally unconvinced of these mainstream views for reasons I mentioned in previous posts.

I'd also like to quote from your link:

It looks to me as if they are offering one possible solution to work such stones with what was available to the people at the time. But I don't think that the same precision and overall caracteristics seen at Sacsayhuamán could be achieved using such methods, especially not on that extremely large scale.

However, I'd still be interested in a pic or clip of what they did during that NOVA show back in 1998, just to have a comparison. Perhaps someone on here can link to existing resources on the web as I couldn't find any related sources myself ...

Your effort in researching mainstream explanations for the construction of these walls is remarkable and that's indeed appreciated. But just as you are not convinced that alternative methods may have been used, I am equally unconvinced of these mainstream views for reasons I mentioned in previous posts.

I'd also like to quote from your link:

Inca TV Broadcast, PBS 1998

Architect Vince Lee helped us figure out one way in which the Inca could have handled the smaller stones. But how the Inca carved and fitted together 100-ton blocks of stone remains a mystery.

/emphasis added/

It looks to me as if they are offering one possible solution to work such stones with what was available to the people at the time. But I don't think that the same precision and overall caracteristics seen at Sacsayhuamán could be achieved using such methods, especially not on that extremely large scale.

However, I'd still be interested in a pic or clip of what they did during that NOVA show back in 1998, just to have a comparison. Perhaps someone on here can link to existing resources on the web as I couldn't find any related sources myself ...

edit on 12-6-2014 by jeep3r because:

spelling

new topics

-

Is the origin for the Eye of Horus the pineal gland?

General Conspiracies: 4 minutes ago -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News: 15 minutes ago -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

2024 Elections: 21 minutes ago -

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness: 57 minutes ago -

Sheetz facing racial discrimination lawsuit for considering criminal history in hiring

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 1 hours ago -

In an Historic First, In N Out Burger Permanently Closes a Location

Mainstream News: 2 hours ago -

MH370 Again....

Disaster Conspiracies: 3 hours ago -

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 5 hours ago -

Chronological time line of open source information

History: 7 hours ago -

A man of the people

Diseases and Pandemics: 8 hours ago

top topics

-

Israeli Missile Strikes in Iran, Explosions in Syria + Iraq

World War Three: 17 hours ago, 18 flags -

In an Historic First, In N Out Burger Permanently Closes a Location

Mainstream News: 2 hours ago, 14 flags -

Thousands Of Young Ukrainian Men Trying To Flee The Country To Avoid Conscription And The War

Other Current Events: 13 hours ago, 7 flags -

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness: 57 minutes ago, 7 flags -

Iran launches Retalliation Strike 4.18.24

World War Three: 16 hours ago, 6 flags -

12 jurors selected in Trump criminal trial

US Political Madness: 16 hours ago, 4 flags -

4 plans of US elites to defeat Russia

New World Order: 10 hours ago, 4 flags -

A man of the people

Diseases and Pandemics: 8 hours ago, 4 flags -

Sheetz facing racial discrimination lawsuit for considering criminal history in hiring

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 1 hours ago, 2 flags -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

2024 Elections: 21 minutes ago, 2 flags

active topics

-

Sheetz facing racial discrimination lawsuit for considering criminal history in hiring

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 5 • : Shoshanna -

12 jurors selected in Trump criminal trial

US Political Madness • 61 • : JadedGhost -

Is the origin for the Eye of Horus the pineal gland?

General Conspiracies • 0 • : JoelSnape -

MH370 Again....

Disaster Conspiracies • 7 • : billxam1 -

ChatGPT Beatles songs about covid and masks

Science & Technology • 23 • : ArMaP -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

2024 Elections • 2 • : xuenchen -

Israeli Missile Strikes in Iran, Explosions in Syria + Iraq

World War Three • 93 • : YourFaceAgain -

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness • 12 • : ImagoDei -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News • 0 • : Mantiss2021 -

Are you ready for the return of Jesus Christ? Have you been cleansed by His blood?

Religion, Faith, And Theology • 16 • : FlyersFan