It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

8

share:

The Five Houses of Zen

Introduction

It is sometimes said of Zen (like its philosophical cousin Taoism) that “he who knows does not speak, and he who speaks does not know.” Be this as it may, there has been much chatter about Zen over the centuries and millennia, and library shelves both east and west groan under the weight of books on this “non-verbal” form of spirituality.

At the risk of adding yet more chatter, I believe there is value to discussing Zen from philosophical and historical perspectives. One doesn’t have to practice something to examine it, and although an analytical approach may not be the same thing as Zen, it can be brought to bear on any topic, including Zen. The ultimate value of such an approach is, of course, for the reader to decide.

Whatever else Zen is, it is a phenomena that has unfolded in history. Like other forms of spirituality, it has its big names and its texts, its schools and sub-schools. This thread takes a brief look at the so-called “Five Houses of Zen,” which took root in China starting in the 9th century AD and provided a general framework of theory and practice for later Zen thinkers and practitioners. Hopefully this information provides one starting place for looking at Zen as a concrete historical, philosophical, and metaphysical phenomenon, rather than a vague hippie-dippy “vibe” about which logical discussion is somehow mysteriously forbidden.

What Are the “Five Houses”?

Zen is often thought of in the West as a Japanese phenomenon, probably because the West became familiar with it on a mass scale through increased contact with Japan following the U.S. occupation after WWII. However, as an identifiable form of Buddhism it originated in China, where it is known as Ch’an. There have been sizable Zen movements in other parts of Asia as well, such as Korea and Vietnam. For convenience and familiarity, though, I will refer to it as “Zen” here.

Zen is not the only form of Buddhism…not even close. It is a sub-category of Mahayana Buddhism (one of the three primary “sub-divisions” of Buddhism). Within Zen, the Five Houses (also called the “Five Schools”) are can be thought of as “flavors” or perhaps “styles” of Zen that each grew out of a different original teacher. They were not originally separate institutions or denominations per se, and there was a some crossover between them. A seeker could study under more than one House of Zen, although if he received formal transmission it usually (but not always) tracked back to one of the Five Houses. Today, of the five, only the Caodong is still practiced formally in China. In Japan, two of them remain living traditions: the Japanese forms of Caodong (called “Soto” in Japanese ) and Linji (“Rinzai” in Japanese).

Zen before the Five Houses

According to tradition (or legend, if you prefer), Zen “began” in India when Gautama Buddha allegedly gave the “Flower Sermon.” Instead of talking, as was usual in his sermons, on this occasion he simply held up a flower and wordlessly showed it to his disciples (as depicted below). All of them remained silent in confusion except Mahakashyapa, who smiled. Tradition has it that only Mahakashyapa understood what was Buddha’s “special transmission, outside of words and texts” on that day, which made him the first Zen master.

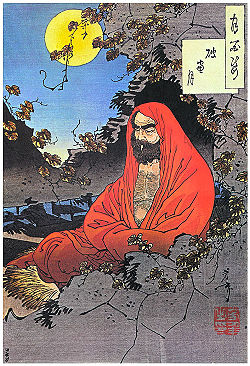

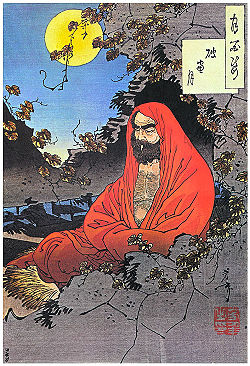

Thus, the story goes, a non-verbal form of direct, experiential enlightenment was passed down directly from the Buddha, through his student Mahakashyapa and in turn through his successors, down the various generations, until we reach the enigmatic figure of Bodhidharma (pic below), who took Zen from India into China in the 5th century AD.

Perhaps because of the Indo-Chinese language barrier, and/or perhaps because of the nature of Zen, Bodhidharma was not a very verbal character. He tried to convey the essence of Zen to his students directly through action or through short, cryptic sayings, rather than relying on the lengthy written teachings (the Sutras) of Buddhism. In him we can see the beginnings of Chinese Zen, with its emphasis on the unreliability of words and texts and the favoring of direct “transmission” of a kind of transcendent, experiential truth. Although words are used in Zen, they are likened to the “finger pointing to the moon” as opposed to the “moon itself,” which is beyond words. Zen tries to keep its students from “mistaking the finger for the moon.” This is, of course, in marked contrast to the Western monotheistic religions, which place central importance on their sacred texts (“the Word”), and it is also in contrast to many of the other forms of Buddhism, some of which can be quite text-oriented as well.

The Buddha himself preached the “doctrine of expedient means,” which allows various different methods to be used to reach the goal of enlightenment (“many roads, one mountain,” as a Zen saying has it). This, perhaps, accounts for the wide variety of practice methods considered valid in Buddhism, from the cryptic puzzles and silent meditation of Zen to the complex rituals of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, to the deep text-based intellectualism and scholarship of the T’ien Tai tradition, to name just three of many examples.

After Bodhidharma passed his wordless “transmission” of direct enlightenment on to his Chinese student Huike, the Zen tradition began to take root in the Middle Kingdom, from which it spread to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. By the time we come to the 9th century, we can begin to think of the Five Houses as separate “streams” into which Bodhidharma’s mighty river of Zen had split.

In the next post, then, I provide a brief outline of each of the Five Houses.

Introduction

It is sometimes said of Zen (like its philosophical cousin Taoism) that “he who knows does not speak, and he who speaks does not know.” Be this as it may, there has been much chatter about Zen over the centuries and millennia, and library shelves both east and west groan under the weight of books on this “non-verbal” form of spirituality.

At the risk of adding yet more chatter, I believe there is value to discussing Zen from philosophical and historical perspectives. One doesn’t have to practice something to examine it, and although an analytical approach may not be the same thing as Zen, it can be brought to bear on any topic, including Zen. The ultimate value of such an approach is, of course, for the reader to decide.

Whatever else Zen is, it is a phenomena that has unfolded in history. Like other forms of spirituality, it has its big names and its texts, its schools and sub-schools. This thread takes a brief look at the so-called “Five Houses of Zen,” which took root in China starting in the 9th century AD and provided a general framework of theory and practice for later Zen thinkers and practitioners. Hopefully this information provides one starting place for looking at Zen as a concrete historical, philosophical, and metaphysical phenomenon, rather than a vague hippie-dippy “vibe” about which logical discussion is somehow mysteriously forbidden.

What Are the “Five Houses”?

Zen is often thought of in the West as a Japanese phenomenon, probably because the West became familiar with it on a mass scale through increased contact with Japan following the U.S. occupation after WWII. However, as an identifiable form of Buddhism it originated in China, where it is known as Ch’an. There have been sizable Zen movements in other parts of Asia as well, such as Korea and Vietnam. For convenience and familiarity, though, I will refer to it as “Zen” here.

Zen is not the only form of Buddhism…not even close. It is a sub-category of Mahayana Buddhism (one of the three primary “sub-divisions” of Buddhism). Within Zen, the Five Houses (also called the “Five Schools”) are can be thought of as “flavors” or perhaps “styles” of Zen that each grew out of a different original teacher. They were not originally separate institutions or denominations per se, and there was a some crossover between them. A seeker could study under more than one House of Zen, although if he received formal transmission it usually (but not always) tracked back to one of the Five Houses. Today, of the five, only the Caodong is still practiced formally in China. In Japan, two of them remain living traditions: the Japanese forms of Caodong (called “Soto” in Japanese ) and Linji (“Rinzai” in Japanese).

Zen before the Five Houses

According to tradition (or legend, if you prefer), Zen “began” in India when Gautama Buddha allegedly gave the “Flower Sermon.” Instead of talking, as was usual in his sermons, on this occasion he simply held up a flower and wordlessly showed it to his disciples (as depicted below). All of them remained silent in confusion except Mahakashyapa, who smiled. Tradition has it that only Mahakashyapa understood what was Buddha’s “special transmission, outside of words and texts” on that day, which made him the first Zen master.

Thus, the story goes, a non-verbal form of direct, experiential enlightenment was passed down directly from the Buddha, through his student Mahakashyapa and in turn through his successors, down the various generations, until we reach the enigmatic figure of Bodhidharma (pic below), who took Zen from India into China in the 5th century AD.

Perhaps because of the Indo-Chinese language barrier, and/or perhaps because of the nature of Zen, Bodhidharma was not a very verbal character. He tried to convey the essence of Zen to his students directly through action or through short, cryptic sayings, rather than relying on the lengthy written teachings (the Sutras) of Buddhism. In him we can see the beginnings of Chinese Zen, with its emphasis on the unreliability of words and texts and the favoring of direct “transmission” of a kind of transcendent, experiential truth. Although words are used in Zen, they are likened to the “finger pointing to the moon” as opposed to the “moon itself,” which is beyond words. Zen tries to keep its students from “mistaking the finger for the moon.” This is, of course, in marked contrast to the Western monotheistic religions, which place central importance on their sacred texts (“the Word”), and it is also in contrast to many of the other forms of Buddhism, some of which can be quite text-oriented as well.

The Buddha himself preached the “doctrine of expedient means,” which allows various different methods to be used to reach the goal of enlightenment (“many roads, one mountain,” as a Zen saying has it). This, perhaps, accounts for the wide variety of practice methods considered valid in Buddhism, from the cryptic puzzles and silent meditation of Zen to the complex rituals of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, to the deep text-based intellectualism and scholarship of the T’ien Tai tradition, to name just three of many examples.

After Bodhidharma passed his wordless “transmission” of direct enlightenment on to his Chinese student Huike, the Zen tradition began to take root in the Middle Kingdom, from which it spread to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. By the time we come to the 9th century, we can begin to think of the Five Houses as separate “streams” into which Bodhidharma’s mighty river of Zen had split.

In the next post, then, I provide a brief outline of each of the Five Houses.

edit on 8/12/2012 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

The House of Linji

臨濟宗

Founding master: Linji Yixuan (died 866)

This austere school emphasized sudden awakening over gradual, and was known for its use of “shock tactics” like hitting, shouting, etc. In Japan it took root as the Rinzai Sect, which was a favorite of the medieval Samurai and survives to this day. Students are given verbal puzzles (such as the famous “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”) called koans with which they must struggle. Enlightenment comes not based on a “correct” answer, but rather based on the way the student ultimately approaches and unravels the koan.

The House of Guiyang

潙仰宗

Japanese name:

Founding masters: Guishan Lingyou (771–854) and Yangshan Huiji (813–890)

The oldest of the Five Houses and now extinct, much information has been lost on this House. Its doctrine involved a fusion of Guishan Lingyou’s teachings about “the unity of principle and function” and Yangshan Huiji’s use of visual symbols and diagrams. Metaphor played an important role in this tradtion. One well-known saying that originated here was “a day without work is a day without food” (一日不做一日不食), showing the value placed on practical work rather than detached contemplation alone.

The House of Caodong

曹洞宗

Founding masters: Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) and Caoshan Benji (840–901)

This school emphasized silent meditiation and “just sitting” over the puzzles and shock tactics of other forms of Zen. Rustic in flavor, it also placed great importance on the humble tasks of daily life (“chop wood, carry water”). In Japan it flourished (and still exists) as the Soto Sect begun by Master Dogen, one of the most famous figures of Japanese Buddhism. Rather than “sudden enlightenment,” it emphasizes a more gradualist approach, and perhaps it can be seen as a slightly gentler form of Zen than that of the other Houses. A Japanese saying is that Soto Zen’s enlightenment is like walking through the mist and gradually discovering that your clothes have become permeated with moisture, while Rinzai (or Linji; see above) is more like having a bucket of water dumped over your head.

The House of Yunmen

雲門宗

Founding master: Yunmen Wenyan (died 949)

The House of Yunmen was gradually absorbed into the House of Linji after several centuries and ceased to exist as a separate school. In its heyday, it was favored by the educated elite in China. Like the House of Linji, it relied much on koans, which in this house were usually extremely short: sometimes only a single word (called “one-word barriers”). The later master Foyin said: of this House’s founder: “When Master Yunmen expounded [doctrine] he was like a cloud. He decidedly did not like people to note down his words. Whenever he saw someone doing this he scolded him and chased him out of the hall with the words, “Because your own mouth is not good for anything, you come to note down my words. It is certain that some day you'll sell me!”

The House of Fayan

法眼宗

Founding master: Fayan Wenyi (885–958)

Another koan-oriented form of Zen, literature and writing was perhaps more central to the House of Fayan than it was to the other Zen Houses. It is the source of many classical Zen biographies of masters and pioneered the formal mechanics of the koan. This form of Zen was also marked by its syncretism, valuing “purity” less and taking techniques and forms of devotion from other types of Buddhism (such as chanting the Nembutsu, or name of Amida Buddha, over and over). Perhaps because of its willingness to borrow from elsewhere, it gradually disappeared as a distinct form of Zen itself, although the writings and traditions that came out of the House of Fayan continue to be respected in Zen to the present day.

edit on 8/12/2012 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

Thanks for this post.

I LOVE Zen. I had a huge breakthrough into the absolute state by wrestling with a koan. Also im a Christian and think Christ was also a zen master

I LOVE Zen. I had a huge breakthrough into the absolute state by wrestling with a koan. Also im a Christian and think Christ was also a zen master

Excellent beautiful thread OP! Very informative and correct! I also love the serene photos of the various buddhist temples. Very cool thread.

The buddhist monk who brought zen to china in the 5th century AD was Da Mo. Da Mo was asked by the emperor of china to come to the capital and help the buddhist monks there translate the sanskrit texts into chinese. When Da Mo arrived at the emperors side he basically found his buddhist believes to be incompatible with that of the emperors. the emperor apparently thought he could go to nirvana if he simply made the texts available to the general population. Although praise worthy it was still far short of what it took to truly reach enlightenment in the eyes of Da Mo.

Da Mo left the emperor and went to the nearest prominent buddhist temple, which was in the adjacent Honan province. There at Song Shan Si he found the monks to be out of shape from transcribing buddhist texts. So he incorporated Dharma yoga movements into their daily curriculum. Eventually he found this to be inadequate so he incorporated martial arts movements he was taught as member of high society in India into the dharma postures to create mindfulness of the movements. This got the monks in shape, taught them a new form of meditation unknown to the monks at the time called Chan (Mandarin)->Zon (Korean)-> Zen (Japanese). These initial 18 movements were called the Lo Han Shi Ba Shou (18 hands of the Lo Han. Lo Han means old man but it translates into an enlightened, scholarly man. Generally a ardent follower of buddha) From these 18 movements came Shi Ba Shi (18 methods) which were the birth of classical Shaolin Kung Fu.

But it all goes back to zen!!!!

The buddhist monk who brought zen to china in the 5th century AD was Da Mo. Da Mo was asked by the emperor of china to come to the capital and help the buddhist monks there translate the sanskrit texts into chinese. When Da Mo arrived at the emperors side he basically found his buddhist believes to be incompatible with that of the emperors. the emperor apparently thought he could go to nirvana if he simply made the texts available to the general population. Although praise worthy it was still far short of what it took to truly reach enlightenment in the eyes of Da Mo.

Da Mo left the emperor and went to the nearest prominent buddhist temple, which was in the adjacent Honan province. There at Song Shan Si he found the monks to be out of shape from transcribing buddhist texts. So he incorporated Dharma yoga movements into their daily curriculum. Eventually he found this to be inadequate so he incorporated martial arts movements he was taught as member of high society in India into the dharma postures to create mindfulness of the movements. This got the monks in shape, taught them a new form of meditation unknown to the monks at the time called Chan (Mandarin)->Zon (Korean)-> Zen (Japanese). These initial 18 movements were called the Lo Han Shi Ba Shou (18 hands of the Lo Han. Lo Han means old man but it translates into an enlightened, scholarly man. Generally a ardent follower of buddha) From these 18 movements came Shi Ba Shi (18 methods) which were the birth of classical Shaolin Kung Fu.

But it all goes back to zen!!!!

edit on 12-8-2012 by BASSPLYR because: (no reason given)

reply to post by silent thunder

you did such an excellent job i hate to even reply in fear of contamination,,, but my view on zen,,, is it is a kind of gymnasium/work out to toughen the mind for living through a human life.,.,,., it is a method of conciousness to deal with existentialism in a light way and heavy way,, by accepting yourself as existing,, and there is nothing you can really do about it, you are accepting yourself as existing,,, you might as well be calm,, and hold this acceptance of existence as some mysterious and personal form of ultimate happiness (bliss) in every moment,, you can dissect any situation or object or occurrence with your mind, you can fear no question or answer or thing,,

this is just some of my train of thought interpretation....

awesome thread though!!!

you did such an excellent job i hate to even reply in fear of contamination,,, but my view on zen,,, is it is a kind of gymnasium/work out to toughen the mind for living through a human life.,.,,., it is a method of conciousness to deal with existentialism in a light way and heavy way,, by accepting yourself as existing,, and there is nothing you can really do about it, you are accepting yourself as existing,,, you might as well be calm,, and hold this acceptance of existence as some mysterious and personal form of ultimate happiness (bliss) in every moment,, you can dissect any situation or object or occurrence with your mind, you can fear no question or answer or thing,,

this is just some of my train of thought interpretation....

awesome thread though!!!

Originally posted by silent thunder

Although words are used in Zen, they are likened to the “finger pointing to the moon” as opposed to the “moon itself,” which is beyond words. Zen tries to keep its students from “mistaking the finger for the moon.” This is, of course, in marked contrast to the Western monotheistic religions, which place central importance on their sacred texts (“the Word”), and it is also in contrast to many of the other forms of Buddhism, some of which can be quite text-oriented as well.

The part of Eastern way of thought I was always so fascinated with. Understanding the world so completely by simple observation.

reply to post by silent thunder

In the west, philosophy and religion are separate, with the former belonging to the Greek-Roman tradition and the latter being Judeo-Christian, traditionally. I get the feeling that with Buddhism this distinction doesn't really exist. It's an interestIng viewpoint that seems to transcend this difference.

In the west, philosophy and religion are separate, with the former belonging to the Greek-Roman tradition and the latter being Judeo-Christian, traditionally. I get the feeling that with Buddhism this distinction doesn't really exist. It's an interestIng viewpoint that seems to transcend this difference.

new topics

-

WF Killer Patents & Secret Science Vol. 1 | Free Energy & Anti-Gravity Cover-Ups

General Conspiracies: 41 minutes ago -

Hurt my hip; should I go see a Doctor

General Chit Chat: 1 hours ago -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues: 2 hours ago -

Michigan school district cancels lesson on gender identity and pronouns after backlash

Education and Media: 2 hours ago -

When an Angel gets his or her wings

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 3 hours ago -

Comparing the theology of Paul and Hebrews

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 4 hours ago -

Pentagon acknowledges secret UFO project, the Kona Blue program | Vargas Reports

Aliens and UFOs: 5 hours ago -

Boston Dynamics say Farewell to Atlas

Science & Technology: 5 hours ago -

I hate dreaming

Rant: 6 hours ago -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News: 8 hours ago

top topics

-

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness: 8 hours ago, 18 flags -

In an Historic First, In N Out Burger Permanently Closes a Location

Mainstream News: 10 hours ago, 16 flags -

A man of the people

Medical Issues & Conspiracies: 16 hours ago, 11 flags -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

Politicians & People: 8 hours ago, 9 flags -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News: 8 hours ago, 8 flags -

Pentagon acknowledges secret UFO project, the Kona Blue program | Vargas Reports

Aliens and UFOs: 5 hours ago, 6 flags -

Michigan school district cancels lesson on gender identity and pronouns after backlash

Education and Media: 2 hours ago, 5 flags -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues: 2 hours ago, 5 flags -

4 plans of US elites to defeat Russia

New World Order: 17 hours ago, 4 flags -

Boston Dynamics say Farewell to Atlas

Science & Technology: 5 hours ago, 4 flags

active topics

-

When an Angel gets his or her wings

Religion, Faith, And Theology • 3 • : BrotherKinsMan -

Hurt my hip; should I go see a Doctor

General Chit Chat • 11 • : TheLieWeLive -

Sheetz facing racial discrimination lawsuit for considering criminal history in hiring

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 7 • : Caver78 -

Silent Moments --In Memory of Beloved Member TDDA

Short Stories • 48 • : Encia22 -

MULTIPLE SKYMASTER MESSAGES GOING OUT

World War Three • 52 • : cherokeetroy -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues • 22 • : Boomer1947 -

WF Killer Patents & Secret Science Vol. 1 | Free Energy & Anti-Gravity Cover-Ups

General Conspiracies • 1 • : WakeofPoseidon -

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness • 67 • : WeMustCare -

Thousands Of Young Ukrainian Men Trying To Flee The Country To Avoid Conscription And The War

Other Current Events • 53 • : ghandalf -

Boston Dynamics say Farewell to Atlas

Science & Technology • 5 • : Caver78

8