It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

13

share:

Note to Mods: I chose to place this in the “Philosophy and Metaphysics” forum rather than “Faith and Theology” because my emphasis here is

on the mystical aspects of the Orthodox tradition, rather than arguing dogma or scriptural/theological points. I hope that what follows will be of

value to anyone with an interest in mystical philosophy and metaphysics, whether Christian or non-Christian, religious or atheist.

Supraessential Radiance:

The Worlds of Orthodox Mysticism

Above: Monestary at Mt. Athos, long an important center of the Orthodox mystical tradition

Introduction

This thread is intended to explore the mysticism of the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition from various angles. I will provide a brief sketch of the mystical tradition as it unfolded in Eastern Orthodox history, with a primary focus on the early Greek/Syriac/Byzantine heritage and the later Russian Orthodox mystics. These are not the only mystical traditions of Eastern Christianity, which is an enormous topic, and thus much will slip through the cracks. Hopefully this thread can serve as a springboard to further exploration, and all who are interested are advised to do their own research. All comments and contributions from any perspective are welcome.

For my part, I plan to structure my main posts in this thread as follows:

Introduction (the post you are now reading)

Part I: What is Orthodox Mysticism?

Part II: The Desert Fathers and Early Orthodox Mysticism

Part III: The Great Medieval Mystics of the Christian East

Part IV: Mystical Russia

This is more or less a chronological approach, anchored in some of the big names. Hopefully after reading this, you will have a rough outline of the major names and themes in Eastern Orthodox mysticism, which will allow you to follow up on what most interests you. If anyone feels I’ve made a mistake or misrepresented anything, by all means let me know. Thank you for reading and I hope you enjoy it.

Supraessential Radiance:

The Worlds of Orthodox Mysticism

Above: Monestary at Mt. Athos, long an important center of the Orthodox mystical tradition

Introduction

This thread is intended to explore the mysticism of the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition from various angles. I will provide a brief sketch of the mystical tradition as it unfolded in Eastern Orthodox history, with a primary focus on the early Greek/Syriac/Byzantine heritage and the later Russian Orthodox mystics. These are not the only mystical traditions of Eastern Christianity, which is an enormous topic, and thus much will slip through the cracks. Hopefully this thread can serve as a springboard to further exploration, and all who are interested are advised to do their own research. All comments and contributions from any perspective are welcome.

For my part, I plan to structure my main posts in this thread as follows:

Introduction (the post you are now reading)

Part I: What is Orthodox Mysticism?

Part II: The Desert Fathers and Early Orthodox Mysticism

Part III: The Great Medieval Mystics of the Christian East

Part IV: Mystical Russia

This is more or less a chronological approach, anchored in some of the big names. Hopefully after reading this, you will have a rough outline of the major names and themes in Eastern Orthodox mysticism, which will allow you to follow up on what most interests you. If anyone feels I’ve made a mistake or misrepresented anything, by all means let me know. Thank you for reading and I hope you enjoy it.

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

Part I: What Is Orthodox Mysticism?

Mysticism in general and Christian Mysticism as a sub-category are both enormous topics, and the phenomena as a whole is beyond the scope of this thread. Here, our task is to focus more precisely on mysticism as it developed in the Orthodox Christian tradition.

To begin with, Eastern Orthodoxy is defined adequately enough at Wikipedia as follows:

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents, mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine, all of which are majority Eastern Orthodox. It is seen by followers to be the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church established by Jesus Christ and his Apostles almost 2,000 years ago.

It can also be thought of as the largest manifestation of Eastern Christianity. The eastern and western forms of Christianity were not generally seen to be separate until the East-West Schism of 1054, after which they formally split from each other.

What distinguishes Orthodox mysticism from other forms of mysticism? What follows is a rough overview of some distinctive aspects of this spiritual path, before we go on to look at specifics.

Theosis: The Mystical Transformation

The term theosis is used by Orthodox mystics to describe the highest mystical experience of divine union. It has been translated many different ways in English, including “ingodding” and “divinization,” but I find none of these words fully satisfactory. In the 4th century, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote about Christ that “He became man that we might be made God.” This idea sounds uncomfortably close to pantheism for many Christians, and arguments about what exactly this means have raged through the centuries. We will explore this further in later posts.

Stages of the Spiritual Journey

Both east and western forms of Christian mysticism often distinguish the journey to mystical union with God as unfolding in three stages. The eastern mode tends to follow the scheme of Evagrius of Pontus (346–399) who conceived of the three as: 1) the active life (seeking freedom from passions and purity of heart); 2) the natural contemplation, (seeing God in all things), and 3) Theoria (encountering God through the union of love). Not all orthodox mystics followed this scheme; for Gregory of Nyssa, who we will look at a bit later, the stages were conceived of as “light”, “cloud,” and “darkness,” for example.

The Path of Negation

The Via Negativa or “Negative Way” (also called apophaticism) is the tendency to describe the Divine in terms of what it “isn’t” rather than what it is. Many (but not all) of the Orthodox mystics emphasize the unknowability of God and the splendor of the divine “mystery.” The Orthodox theologians were less analytical than their medieval European counterparts, who tried to express their faith in terms of logic and rational thought. Emptiness, darkness, silence, voidness, and similar “negative” formulations are used more heavily in the Christian east to describe the Divine and the mystical experience. To approach God, one had to empty and still the mind through mystical prayer.

Mystical Prayer

Contemplative prayer is of key importance in the Orthodox mystic’s quest for union with God. The mystic seeks a state known as hesychia, or “inner stillness,” transcending discursive thinking to achieve direct union with the Divine. Many methods of prayer are used in the Orthodox tradition. We will look at one of the most well-know a bit later, the so-called “Jesus prayer.” Constantly repeated thousands of times a day, it starts as a “prayer of the lips,” becomes a “prayer of the mind,” and then finally a “prayer of the heart,” focusing the mystic’s consciousness on the presence of God in a quest for spiritual illumination. It has been compared to the mantras of Hinduism and Buddhism, although important differences exist. Orthodox mystical prayer tends to rely less on complex visualization (as with Catholic discursive prayer or Buddhist visualization, for example), with more emphasis on stillness, silence, and the divine darkness of unknowing.

The Patristic Way

The so-called Early Church Fathers were writers in the first few centuries after Christ who hammered out the philosophical specifics of Christian thought, mystical and otherwise. They are generally respected by Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians alike, but their writings play a much more prominent role in the Orthodox tradition. The Church Fathers and the so-called Desert Fathers wrote much on mysticism and spirituality, and their writings provide the philosophical and theoretical backbone of Orthodox mysticism.

The Icon

The Icon is a special form of religious painting that plays a complex role in Orthodox mysticism. The image is not worshiped, but rather is seen as a kind of “portal” through which the numinous dimension of the Divine can be accessed. An Icon is both a symbolic representation of a divine truth and a visual tool with spiritual and mystical applications.

A Kaleidoscope of Mystical Traditions

We can only scratch the surface here, but the mystical experience has been formulated in a bewildering variety of ways in the Orthodox tradtion. Many local saints, monks, wanderers, and holy men had their own idiosyncratic mystical teachings. Some emphasized asceticism and renunciation of the world, other preached a more active life. Some wrote of the Divine in terms of unknowable darkness, others celebrated the splendor of the light that emanated from God. Austere paths of self-denial were central to some, while others celebrated a mystical love. others c In different times and places, Orthodox mysticism was formulated very differently. This glittering variety makes the study of this type of spirituality all the more interesting.

(Next - Part II: The Desert Fathers and Early Orthodox Mysticism)

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

Part II: The Desert Fathers and Early Orthodox Mysticism

The roots of Orthodox mysticism are complex, with numerous imputs. Events in the life of Christ, the sudden conversion of Paul, and certain experiences of the Apostles are usually cited in discussions on earliest forms of Christian mysticism. The Gnostic sects, Jewish mysticism, and Neoplationism had some influence on the course on the development of early Orthodox spirituality. During the historical epoch known as “Late Antiquity,” many different spiritualities and philosophies were interacting and influencing each other, from Egyptian and Hermetic ideas to Chaldean, Persian, and even Indian thought.

The so-called Church Fathers and Desert Fathers are respected by most forms of Christianity, but they have been particularly influential on Orthodox thinkers and mystics. We will look at a few important examples below.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 to 215)

Not much is known about Clement’s life. He was head of the so-called Catechetical School in the city of Alexandria. During the time, many different ideas and faiths were swirling together in this dynamic city. He was the first to use the word “mysticism” with reference to Christianity.

Key mystical teachings:

Origen (c. 185 - 254)

Origin was another Aleandrian, and a pupil of Clement’s who succeeded him as the leader of the Catechetical School. He wrote on many subjects and was very influential in both Eastern and Western theology, although he was controversial and many of his ideas have been considered heretical.

Key mystical teachings:

(Part II is continued in the next post)

The roots of Orthodox mysticism are complex, with numerous imputs. Events in the life of Christ, the sudden conversion of Paul, and certain experiences of the Apostles are usually cited in discussions on earliest forms of Christian mysticism. The Gnostic sects, Jewish mysticism, and Neoplationism had some influence on the course on the development of early Orthodox spirituality. During the historical epoch known as “Late Antiquity,” many different spiritualities and philosophies were interacting and influencing each other, from Egyptian and Hermetic ideas to Chaldean, Persian, and even Indian thought.

The so-called Church Fathers and Desert Fathers are respected by most forms of Christianity, but they have been particularly influential on Orthodox thinkers and mystics. We will look at a few important examples below.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 to 215)

Not much is known about Clement’s life. He was head of the so-called Catechetical School in the city of Alexandria. During the time, many different ideas and faiths were swirling together in this dynamic city. He was the first to use the word “mysticism” with reference to Christianity.

Key mystical teachings:

- Some non-Christian ideas, such as from classical philosophy, are also gifts from God, although subordinate to scripture. Clement tried to

Christianize a number of neo-Platonic ideas.

- “True gnosis” is different from the “false gnosis” of the so-called Gnostic Christian sects. True gnosis is not necessary for salvation,

but a gift from Christ, a special direct experience of the Divine accessible through spiritual discipline. By achieving a state of

“passionlessness,” the mystical seeker attempts to “become like God.”

- The mystical journey has three steps, which can be compared to the three days of Abraham’s journey in Genesis: “the perception of beauties”

is followed by “the desire of the good soul,” and finally “the eyes of the understanding [are] opened by the Teacher who rose again the third

day.” If God grants the seeker success with the highest contemplation as a special gift, Christ “seals the divine image upon the soul."

- Clement distinguished “contemplation” and “action” on the spiritual journey, using the Mary and Martha story from the Book of Luke as a

symbol to explain these two types of spirituality.

Origen (c. 185 - 254)

Origin was another Aleandrian, and a pupil of Clement’s who succeeded him as the leader of the Catechetical School. He wrote on many subjects and was very influential in both Eastern and Western theology, although he was controversial and many of his ideas have been considered heretical.

Key mystical teachings:

- Scripture is full of many rich spiritual meanings, in the form of metaphor and allegory. Scripture should not be read narrowly or as literal truth;

rather, it should be contemplated more mystically, to draw out the “secret and hidden things of God” within.

- Self-denial, discipline, ascetic practices, mortification of the flesh, renunciation of sexuality, annihilation of base desire, and the like are

roads to mystical experience. Origen was very severe in his asceticism and it is said he castrated himself as a young man in an attempt to combat

desire.

- The soul is created in the image of God, and this evidence of special connection between the human mind and God. God can be approached

successively, in stages.

- The Song of Songs expresses the mystery of union of the soul and God, and of the Church and God. Origen saw three different levels of

meanings: 1) as a simple and passionate wedding poem; 2) as an expression of Christ’s love for Christians, and an expression of the hunger of the

soul for the divine Word.

(Part II is continued in the next post)

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

(Part II, continued from above)

The Desert Fathers

Influenced by the thought of Clement and Origin, as well as the life of Christ himself, increasing numbers of men and women began to withdraw to the desert to live quiet lives of solitude and spiritual struggle. Most of these mystics embraced poverty, prayer, fasting, solitude, and ascetic self-denial as a way to escape the world and turn inward, pursuing divine illumination. Mostly solitary at first, the first Christian monestaries developed out of this tendency to solitude and renunciation.

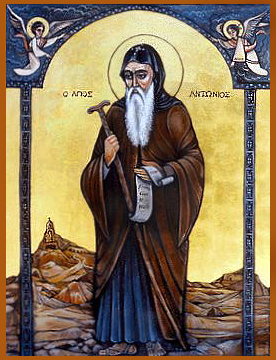

The most well-known Desert fathers include Anthony the Great (pictured above), Abba Arsenius, Abba Poemen, Abba Macarius of Egypt, Abba Moses the Robber, and Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, Pachomius and Shenouda the Archimandrite. Their sayings have been collected in works such as The Paradise of the Desert Fathers, and cherished by generations of mystical seekers.

Gregory of Nyssa (330-395)

Along with his brother Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory of Nyssa is one of the three great “Cappadocian Fathers.” After many years as a solitary monk, Gregory took on a more active role as a bishop and a leading theologian.

Key mystical teachings:

Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500)

This author is sometimes called “Pseudo-Dionysius” because the name he wrote under was that of an earlier figure in Christian history. His Mystical Theology is perhaps the most influential and towering work of early Christian mysticism, and it had an enormous influence in both the Eastern and Western churches.

Key mystical teachings:

(Next - Part III: The Great Medieval Mystics of the Christian East)

The Desert Fathers

Influenced by the thought of Clement and Origin, as well as the life of Christ himself, increasing numbers of men and women began to withdraw to the desert to live quiet lives of solitude and spiritual struggle. Most of these mystics embraced poverty, prayer, fasting, solitude, and ascetic self-denial as a way to escape the world and turn inward, pursuing divine illumination. Mostly solitary at first, the first Christian monestaries developed out of this tendency to solitude and renunciation.

The most well-known Desert fathers include Anthony the Great (pictured above), Abba Arsenius, Abba Poemen, Abba Macarius of Egypt, Abba Moses the Robber, and Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, Pachomius and Shenouda the Archimandrite. Their sayings have been collected in works such as The Paradise of the Desert Fathers, and cherished by generations of mystical seekers.

Gregory of Nyssa (330-395)

Along with his brother Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory of Nyssa is one of the three great “Cappadocian Fathers.” After many years as a solitary monk, Gregory took on a more active role as a bishop and a leading theologian.

Key mystical teachings:

- The mystical life is described in terms of the unending ascent of the soul to God, with successive realizations leading the seeker closer to

God’s ultimate mystery. The divine element in every soul is an “inner eye” that can be opened to the vision of the sacred. And yet the more one

advances, the greater the mystery, which Gregory describes as the “darkness” or hiddenness of the face of God.

- Gregory praised the solitary spirituality of the desert hermits, and practiced as a monk himself for many years. Ultimately, however, he believes

contemplation must manifest as action in the real world. Ideally, the most accomplished mystics should be able to maintain the stillness of desert

spirituality inside themselves, while engaging actively with the “real world.”

- For Gregory, spiritual life is a continual progression and a journey without end, rather than an unchanging state of perfection. The progress of a

mystic in this world is never completed.

Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500)

This author is sometimes called “Pseudo-Dionysius” because the name he wrote under was that of an earlier figure in Christian history. His Mystical Theology is perhaps the most influential and towering work of early Christian mysticism, and it had an enormous influence in both the Eastern and Western churches.

Key mystical teachings:

- God cannot be known intellectually, but he can be experienced mystically though spiritual discipline. Dionysius speaks of seeking God with an

“eyeless mind.”

- God should be conceived of in terms of what he is not, rather than what he is. It is blasphemous and wrong to use the imperfect

images of our mind drawn from this fallen world to envision God, a higher order being altogether. By stripping away false ideas of God, we draw closer

to God.

- Dionysius describes the three stages of the soul’s movement toward God as Purification, Illumination, and Union. This is similar to the threefold

scheme of earlier mystics, although envisioned differently by Dionysius.

- Dionysius wrote: “Ascending upwards from particular to universal conceptions we strip off all qualities in order that we may attain a naked

knowledge of that Unknowing which in all existent things is enwrapped by al objects of knowledge, and that we may begin to see that super-essential

Darkness which is hidden by all the light that is in existent things.” He says God “plunges the true initiate into the Darkness of Unknowing [to

belong] wholly to Him who is beyond all things and to no one else [and to gain] a knowledge that exceeds understanding.”

(Next - Part III: The Great Medieval Mystics of the Christian East)

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

Part III: The Great Medieval Mystics of the Christian East

As time went on, the Western and Eastern churches drew apart, developing in different directions. The mystics we will look at here perhaps represent the “mature phase” of Orthodox mysticism, as this spiritual tradition became more complex and well-defined.

Maximus the Confessor (c. 580 - 662)

Maximus the Confessor is considered by many to stand at the pinnacle of Orthodox theology. He commentated on Gregory of Nyssa and Dionysius, developing various aspects of earlier mystical thought while also being a completely original thinker. His mysticism is mature, subtle, complex, and of lasting importance.

Key mystical teachings:

John Climacus (579–649)

This monk and abbot deserves brief mention for his work The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which systematized the mystical quest in great detail and achieved vast popularity throughout the Christian east. The work uses the image of Jacob’s ladder from the book of Genesis to describe the ascent of the mystic to God. John Climacus’s ladder (see image above) had thirty “rungs” or stages by which the mystic draws closer to the Divine. Renunciation of worldly things is followed by penitence, defeat of vices and acquisition of virtue, and avoidance of certain spiritual traps (laziness, pride, mental stagnation), and finally the mystic achieves hesychia (“inner stillness”) and apatheia (“dispassion” or “detachment”). Nevertheless, as seen in the image above, one can always tumble from the ladder and away from the Divine, no matter how advanced.

(Part III is continued in the next post)

As time went on, the Western and Eastern churches drew apart, developing in different directions. The mystics we will look at here perhaps represent the “mature phase” of Orthodox mysticism, as this spiritual tradition became more complex and well-defined.

Maximus the Confessor (c. 580 - 662)

Maximus the Confessor is considered by many to stand at the pinnacle of Orthodox theology. He commentated on Gregory of Nyssa and Dionysius, developing various aspects of earlier mystical thought while also being a completely original thinker. His mysticism is mature, subtle, complex, and of lasting importance.

Key mystical teachings:

- All of creation is filled with the energeia, or activity of God, which shapes the universe. God himself remains incomprehensible and beyond

human minds, but man can achieve mystical union with God through love.

- In The Four Hundred Chapters on Love, the central importance of love and empathy are highlighted. Maximus believed that the mystical quest

should be integrated with love, empathy, charity, and love of knowledge.

- Detachment was crucial for Maximus, who wrote it “is impossible to reach the habit of this love if one has any attachment to earthly things.”

Detachment from worldly desires and complications allows love for God, which in turn brings a more profound detachment.

- The human being stands as a mediator between God and the cosmos. God has become man through Christ, and this fusion of the human and the divine is

realized again in the mystic journey, as the seeker pursues mystic union through ecstatic love. Maximus wrote of perichoresis, or a kind of

interpenetration of man and God that allows both to be united with each other without losing their separate identities.

John Climacus (579–649)

This monk and abbot deserves brief mention for his work The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which systematized the mystical quest in great detail and achieved vast popularity throughout the Christian east. The work uses the image of Jacob’s ladder from the book of Genesis to describe the ascent of the mystic to God. John Climacus’s ladder (see image above) had thirty “rungs” or stages by which the mystic draws closer to the Divine. Renunciation of worldly things is followed by penitence, defeat of vices and acquisition of virtue, and avoidance of certain spiritual traps (laziness, pride, mental stagnation), and finally the mystic achieves hesychia (“inner stillness”) and apatheia (“dispassion” or “detachment”). Nevertheless, as seen in the image above, one can always tumble from the ladder and away from the Divine, no matter how advanced.

(Part III is continued in the next post)

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

(Part III, continued from above)

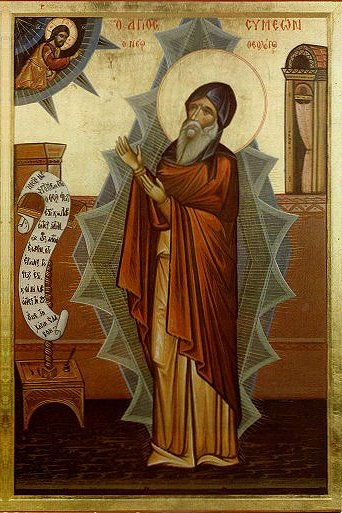

Symeon the New Theologian (949–1032)

Symeon’s thought is rooted in tradition, but he provided a fresh approach to mysticism and new ways of thinking about timeless spiritual truths. His bold and original style was to have a massive influence on the development of mystical prayer, which took on more and more importance in the Orthodox world as time went on.

Key mystical teachings:

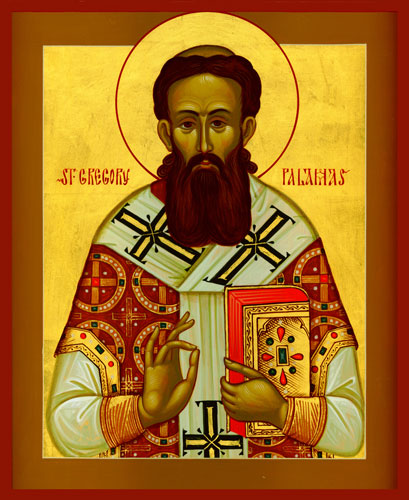

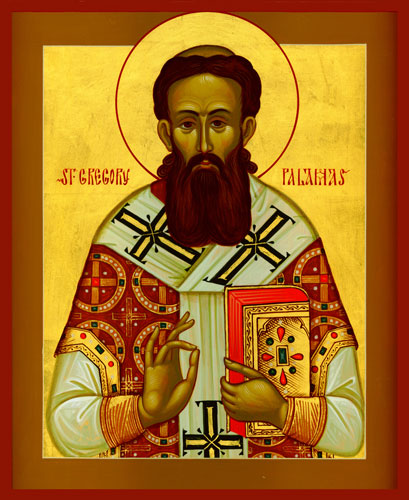

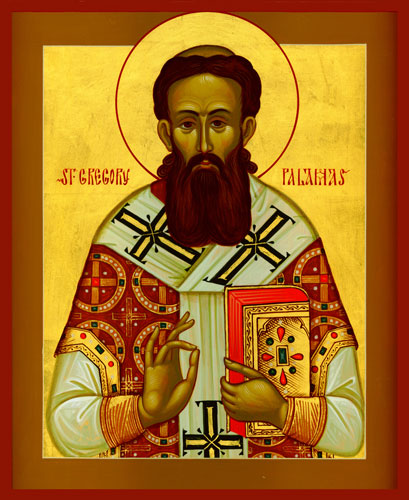

Gregory of Palamas (1296–1359)

Gregory of Palamas made an enduring contribution to Orthodox mysticism with his defense of and codification of the Hesychast tradition (see below) and divine prayer. These concepts were to dominate the later history of Orthodox mysticism, and he provided a strong philosophical foundation for later mystics to build on.

Key mystical teachings:

(Next - Part IV: Mystical Russia)

Symeon the New Theologian (949–1032)

Symeon’s thought is rooted in tradition, but he provided a fresh approach to mysticism and new ways of thinking about timeless spiritual truths. His bold and original style was to have a massive influence on the development of mystical prayer, which took on more and more importance in the Orthodox world as time went on.

Key mystical teachings:

- Symeon affirmed the insights of earlier mystics, but he also asserted that God was not simply a distant and unknowable figure: God can be accessed

here and now, in daily life, by laypeople as well as monks. Symeon wrote: “[A man] who has wife and children, crowds of servants, much property, and

a prominent position in the world …[can live] a heavenly life here on earth…not just in caves or mountains or monastic cells, but in the midst of

cities.”

- Symeon used the light rather than darkness in his symbolism when considering mystical union with God. Union comes through a vision of divine

radiance: “We bear witness that God is light, and that those counted worthy to see him have all beheld him as light, and those who have received him

have received him as light, for the light of his glory goes before him.”

- In his Hymns of Divine Love, Symeon describes his own mystical experiences, providing a personal perspective that is rare in orthodox mystic

writing. The Hymns are poetic meditations on the contemplation of God as a “light and fire” and a divine outpouring experienced as an

“indwelling” of the sacred. Visions of Christ as a more personal, less distant figure and a sense of mystical union with Christ through the

mystery of the blood are also present in Symeon’s work. All of these factors make him stand out sharply from earlier strains of Orthodox

mysticism.

Gregory of Palamas (1296–1359)

Gregory of Palamas made an enduring contribution to Orthodox mysticism with his defense of and codification of the Hesychast tradition (see below) and divine prayer. These concepts were to dominate the later history of Orthodox mysticism, and he provided a strong philosophical foundation for later mystics to build on.

Key mystical teachings:

- Like Symeon, Gregory of Palamas spoke of the sacred in terms of in light rather than darkness. The mystical prayer of the heart can lead the seeker

to a vision of the divine light, identical with the brilliant luminescence of Christ’s transfiguration on Mount Tabor. The essence of God

remains unknowable, but the divine energies permeate all things and are experienced in the form of “deifying grace.”

- Palamas was an important defender of hesychasm, a Byzantine movement that fused mystical contemplation, ascetical ideals, repetitive prayer

(especially the “Jesus Prayer”), special bodily postures, attention to heartbeat, and controlled breathing. During the lifetime of Palamas,

hesychasm came under attack, but he successfully defended its legitimacy in debate and helped to develop and clarify the full practice.

- In hesychast mystical prayer, the seeker sits with head down and gaze directed toward the belly or heart. Prayer, rhythmic breathing, and sometimes

heartbeat are carefully synchronized. Many have compared hesychast prayer to yogic exercises of East Asian mysticism. This tradition could be

practiced and handed down simply without schools or literature, and helped Eastern Christianity to survive the 400-year Muslim occupation after

Constantinople fell in 1453. It also spread widely throughout the Balkins, the Slavic world, and especially Russia, where Orthodox Mysticism was to

take root and flourish vigorously.

(Next - Part IV: Mystical Russia)

edit on 2/18/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

thank you for more to look into

had not heard of this before now as i continue to search for my answers the puzzle seems to grow

much to read and each new source leads me to 3-7 new areas to research

as a being on this planet who believes we have something forgotten i THANK YOU for more pieces of a never ending puzzle to research and hope to find a couple nuggets

if you have more pls post

had not heard of this before now as i continue to search for my answers the puzzle seems to grow

much to read and each new source leads me to 3-7 new areas to research

as a being on this planet who believes we have something forgotten i THANK YOU for more pieces of a never ending puzzle to research and hope to find a couple nuggets

if you have more pls post

reply to post by silent thunder

Truly an awesome thread, silent thunder.

I have been thinking about this stuff intensely over the past few days and actually used the search function to see what was on ATS and there you were.

I use the prayer of the heart in my own practice. I was wondering if you had encountered the writing of William Ryan?

www.bahaistudies.net...

I don't know how the Bahai folks became the keepers of the .pdf, but there it is.

I have experimented with a lot and the Jesus Prayer has boiled down to my favorite.

Thanks again, your thread is wonderful. Have a great Sunday.

X.

Truly an awesome thread, silent thunder.

I have been thinking about this stuff intensely over the past few days and actually used the search function to see what was on ATS and there you were.

I use the prayer of the heart in my own practice. I was wondering if you had encountered the writing of William Ryan?

www.bahaistudies.net...

I don't know how the Bahai folks became the keepers of the .pdf, but there it is.

I have experimented with a lot and the Jesus Prayer has boiled down to my favorite.

Thanks again, your thread is wonderful. Have a great Sunday.

X.

This is such a great thread, to echo the sentiments of others. It's hard to find this information in short "digest form" in English...so thanks. I'll

be looking forward to the next installment on Russia.

It is fascinating how much some of this stuff resembles the spiritualities of Asia. It really makes you wonder about the univerisality of mysticsm, which seems to be found in one form or another in almost every religion, and with eerie similarities across cultures. This fact alone makes it worth of careful scrutiny, whether or not you are a "believer."

Looking at the picture of Gregory of Palamas posted above, I was reminded of something. It took me a minute, but I figured it out, and it made the hair on my arms stand up. Look at the hands in the pictures below - "when you see it, you'll **** *****," as they say:

It is fascinating how much some of this stuff resembles the spiritualities of Asia. It really makes you wonder about the univerisality of mysticsm, which seems to be found in one form or another in almost every religion, and with eerie similarities across cultures. This fact alone makes it worth of careful scrutiny, whether or not you are a "believer."

Looking at the picture of Gregory of Palamas posted above, I was reminded of something. It took me a minute, but I figured it out, and it made the hair on my arms stand up. Look at the hands in the pictures below - "when you see it, you'll **** *****," as they say:

edit on 2/20/2012 by FailedProphet because: (no reason given)

Absolutely amazing thread silent thunder and I'm really surprised it hasn't received more attention.

I’ve always loved images from orthodox iconography and this thread has taught me a lot about a subject which I’ve only briefly ever looked into.

Just goes to show when you really look past the face of many belief systems how similar many of them are at the mystic core….

I’ve always loved images from orthodox iconography and this thread has taught me a lot about a subject which I’ve only briefly ever looked into.

Just goes to show when you really look past the face of many belief systems how similar many of them are at the mystic core….

edit on 20/2/2012 by 1littlewolf because: (no reason given)

reply to post by silent thunder

You know that first picture in your op does seem familiar to me, I think I'v been there. Or maybe not, but one of these orthodox monasteries I have been to and remember that is as cool if not cooler.

Is this place in Greece.... Meteora.

The place is on a mountain range area, took a while to get there, and when you get there you still have to get up to the monastery by foot, if your wondering why would I would go there since I suck at being religious. Well I didn't want to! but my cousins who live and work in Greece wanted to show us this place since they been there before, and my parents wanted to see it, and so I ended up tagging along.

I tough't it was going to suck, since I had to tag along with them to other such monasteries in the eastern Europe and Greece, but most of them were cool, some were alright, others were kind of meh, all in all this whole religion subject is not my thing.

This place however was pretty interesting, especially given the fact that it was build on giant sandstone rock pillars, and once you get up top and look down at the valley it is a pretty impressive sight to see, even the little town bellow.

And it was impressive what the monks and people who build them were able to achieve, they even had little pulleys to bring things, materials and people up there to those heights once they brought it to the bottom of the rock pillars, and even getting the materials or anything to the area to start building anything must of been a pain back then. But I can picture them doing there meditations/prayers then pulling rocks, mortar, bricks and other necessities up to build those places...And then, well they say them monks loved there wine.

I think I have some pictures of me at that place somewhere in some drawer or under the bed in a folder. But here is a youtube vid, with some time lapse effects for better visualization of the area, and the wiki "Meteora" has pictures which is right on the dot to my memory of how those monasteries looked.

I am sure all religions are just rehashes of something that sprang from the same source, even the whole mysticism can be seen everywhere all throughout the globe being interpreted differently, by different peoples, and different sources, in there own peculiar and particular ways.

Sometimes adding to things, sometimes taking things away, but its just a constantly moving and put together picture in peoples minds, sometimes that picture is dissembled to fit a mold, and once in a while it's an evolving picture that evolves to something totally different... And sometimes not.

But mostly it seems to be reinterpretations and expressions of the current age you happen to look at, like a still frame into that time and place, and a view into its mind frames of the era, which is not unlike looking at the fashions of the era.

You know that first picture in your op does seem familiar to me, I think I'v been there. Or maybe not, but one of these orthodox monasteries I have been to and remember that is as cool if not cooler.

Is this place in Greece.... Meteora.

The place is on a mountain range area, took a while to get there, and when you get there you still have to get up to the monastery by foot, if your wondering why would I would go there since I suck at being religious. Well I didn't want to! but my cousins who live and work in Greece wanted to show us this place since they been there before, and my parents wanted to see it, and so I ended up tagging along.

I tough't it was going to suck, since I had to tag along with them to other such monasteries in the eastern Europe and Greece, but most of them were cool, some were alright, others were kind of meh, all in all this whole religion subject is not my thing.

This place however was pretty interesting, especially given the fact that it was build on giant sandstone rock pillars, and once you get up top and look down at the valley it is a pretty impressive sight to see, even the little town bellow.

And it was impressive what the monks and people who build them were able to achieve, they even had little pulleys to bring things, materials and people up there to those heights once they brought it to the bottom of the rock pillars, and even getting the materials or anything to the area to start building anything must of been a pain back then. But I can picture them doing there meditations/prayers then pulling rocks, mortar, bricks and other necessities up to build those places...And then, well they say them monks loved there wine.

I think I have some pictures of me at that place somewhere in some drawer or under the bed in a folder. But here is a youtube vid, with some time lapse effects for better visualization of the area, and the wiki "Meteora" has pictures which is right on the dot to my memory of how those monasteries looked.

I am sure all religions are just rehashes of something that sprang from the same source, even the whole mysticism can be seen everywhere all throughout the globe being interpreted differently, by different peoples, and different sources, in there own peculiar and particular ways.

Sometimes adding to things, sometimes taking things away, but its just a constantly moving and put together picture in peoples minds, sometimes that picture is dissembled to fit a mold, and once in a while it's an evolving picture that evolves to something totally different... And sometimes not.

But mostly it seems to be reinterpretations and expressions of the current age you happen to look at, like a still frame into that time and place, and a view into its mind frames of the era, which is not unlike looking at the fashions of the era.

Thanks for your replies and for reading, people. I'm glad you found this interesting.

I'll be putting part IV out in a few days, hopefully. It's taking me a while to sort through all my notes about developments in Russia. It's a bit shocking to me how little systematically organized information about the Russian mystics there is in English, from a big-picture perspective. Lots of little bits and pieces here and there, but not many attempts seem to have been made to string it all together for an overview, at least that I can find. I'll see what I can do to remedy that to some little extent, for ATS at least.

I'll be putting part IV out in a few days, hopefully. It's taking me a while to sort through all my notes about developments in Russia. It's a bit shocking to me how little systematically organized information about the Russian mystics there is in English, from a big-picture perspective. Lots of little bits and pieces here and there, but not many attempts seem to have been made to string it all together for an overview, at least that I can find. I'll see what I can do to remedy that to some little extent, for ATS at least.

What's the difference between Eastern Orthodox and Catholic mysticism?

Originally posted by 0thetrooth0

What's the difference between Eastern Orthodox and Catholic mysticism?

This is a good question. The answer, of course, is that it depends on who you talk to. If you were asking me - an open-minded and basically impartial amateur observer - I would start out by saying that at the peak, all valid mysticisms seem to reach the same end, which is direct experience of something sacred and experienced as beyond ordinary consciousness/reality. I'd even go so far as to say a kind of "atheist mysticism" is probably possible, based on psychological or neurological perspectives and techniques.

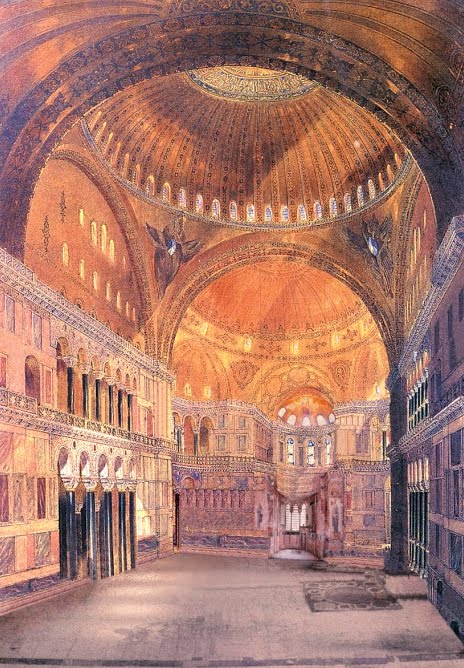

Beyond that level, drilling down and looking specifically at Catholic vs. Orthodox mysticism, both are rooted in the ideas and traditions of the Early Church Fathers, as noted above. As time goes on, you start to see clearer differences emerge. The second post of this thread gives an outline of some of the most distinctive aspects of Orthodox mysticism. The use of icons and the emphasis on mystical prayer (i.e., hesychasm) both strike me as strongly "Orthodox-rather-than-Catholic." A lot of the differences are cultural -- art, language, ritual, architecture, and so on; the "feel" or "flavor" of eastern vs. western European culture, going back to the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, and even earlier. Aesthetic or cultural factors lose their meaning the closer the seeker gets to the peak of the mystical journey, but they are significant in the earlier stages, when actual paths and practices take shape.

I think mysticism also had a more solid place in the Orthodox Church in many ways. It is celebrated very prominently in Orthodox literature, theology, and philosophy. Catholicism certainly never denied mysticism, and produced many first-rank mystics, of course. But my impression is that the Catholic Church always had a more troubled relationship with its mystics. Mysticism was tolerated, but often vaguely suspicious, seen to be apt to wander off the deep end into pantheism or other forms of "heresy" if not tightly regulated. Orthodoxy had its heresies, controversies, and persecutions, too, but on a much more subdued scale than western Catholics, with their wars on the mystically-oriented Cathers, witch hunts, inquisitions, struggles with European indigenous paganism, and millenium-long obsession with sniffing out distant echoes of ancient enemies like Priscillianism or Gnosticism.

Catholic philosophers have always thought the Orthodox mystics strayed too close to pantheism. The Orthodox were aware of the matter and never quite formulated their ideas in as openly pantheistic terms as Buddhists or Hindus have often done. Both Catholics and Orthodox always try to maintain some kind of distinction between man and God. However, it appears the Orthodox are comfortable closer to that fuzzy line, with concepts like theosis and Maximus the Confessor's perichoresis or "interpenetration" of God and man (see above). Some medieval Western European mystics (Eckhart, Suso, and Tauler come to mind) also skate close to - and sometimes perhaps over - the same line, it should be remembered. But these figures have been much more marginal in Catholic tradition than the Orthodox mystics were in their sphere.

Mystical prayer is another area where big differences can be seen. The repetitive prayer and body/breath/heart work of hesychasm was more or less alien to Catholic west Europe. Meanwhile the Catholics developed complex forms mystical visualization (so-called "discursive prayer", for example) that don't seem to have had much presence in the Orthodox east.

edit on 2/23/12 by silent thunder because: (no reason given)

Originally posted by silent thunder

We will look at one of the most well-know a bit later, the so-called “Jesus prayer.” Constantly repeated thousands of times a day, it starts as a “prayer of the lips,” becomes a “prayer of the mind,” and then finally a “prayer of the heart,” focusing the mystic’s consciousness on the presence of God in a quest for spiritual illumination.

Is that like the Catholic 'centering prayer'?? Catholic 'centering prayer' is controversial in Catholic circles.

is it the same or different ... can you compare them for me if they are different? Thanks.

It has been compared to the mantras of Hinduism and Buddhism, although important differences exist. Orthodox mystical prayer tends to rely less on complex visualization (as with Catholic discursive prayer or Buddhist visualization, for example), with more emphasis on stillness, silence, and the divine darkness of unknowing.

The Catholic mystics (like St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross) talk about that stillness.

Is that 'divine darkness of unknowning' related to the Buddhist concept of no 'I', no 'personality"?

Or am I thinking along a totally different path than where you are headed with this?

Side note - you brought up the desert fathers ... one I like to read about -

Saint Antony of the Desert (Egypt). Very interesting fella ... mystic .... spiritual father.

Originally posted by silent thunder

Catholicism certainly never denied mysticism, and produced many first-rank mystics, of course. But my impression is that the Catholic Church always had a more troubled relationship with its mystics.

I don't know .. there are a lot of authentic mystics in the Catholic church. From St. Teresa of Avila, to St. John of the Cross, to St. Benedict, to St. Francis , St. Padre Pio, ... etc. TODAY the Catholic church tends to be embarrassed by it all. It's gotten so modern. But the church does still talk about 'the prayer of quiet', and the rest ... you just have to get away from the parishes to find it ... go to the monasteries or convents (and not the 'modern' ones) .... find the good books that discuss ST. John of the Cross, etc etc

Holy Spirit Monastery outside Atlanta Georgia. I was on a three day retreat there 15 years ago.

If you were to attend Compline there .. you'd know that mysticism is alive and well ..

reply to post by FlyersFan

I used to love that place and I was an atheist at the time. I lived a couple of miles from there and would go and sit during the day sometimes just for some peace and quiet during contemplation. I loved the bread they made and the trees and plants they grew. Have not been back to Atlanta in years but definitely will stop there again if I get the chance.

To the OP did the Russian Mystics portion of this thread ever get made? I did not see it using search. I am quite interested in this subject simply because Eastern Orthodox is something I am not overly familiar with aside from some of the major historical events.

I used to love that place and I was an atheist at the time. I lived a couple of miles from there and would go and sit during the day sometimes just for some peace and quiet during contemplation. I loved the bread they made and the trees and plants they grew. Have not been back to Atlanta in years but definitely will stop there again if I get the chance.

To the OP did the Russian Mystics portion of this thread ever get made? I did not see it using search. I am quite interested in this subject simply because Eastern Orthodox is something I am not overly familiar with aside from some of the major historical events.

reply to post by silent thunder

Long Post. Good effort.

Just wonderin, if being Born Again in Eastern orthodoxy exists or otherwise.

Do they believe in being Saved by The Blood and Mighty Grace of Jesus.

Long Post. Good effort.

Just wonderin, if being Born Again in Eastern orthodoxy exists or otherwise.

Do they believe in being Saved by The Blood and Mighty Grace of Jesus.

new topics

-

The good, the Bad and the Ugly!

Diseases and Pandemics: 54 minutes ago -

Russian intelligence officer: explosions at defense factories in the USA and Wales may be sabotage

Weaponry: 3 hours ago -

African "Newcomers" Tell NYC They Don't Like the Free Food or Shelter They've Been Given

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 4 hours ago -

Russia Flooding

Other Current Events: 5 hours ago -

MULTIPLE SKYMASTER MESSAGES GOING OUT

World War Three: 6 hours ago -

Two Serious Crimes Committed by President JOE BIDEN that are Easy to Impeach Him For.

US Political Madness: 7 hours ago -

911 emergency lines are DOWN across multiple states

Breaking Alternative News: 7 hours ago -

Former NYT Reporter Attacks Scientists For Misleading Him Over COVID Lab-Leak Theory

Education and Media: 9 hours ago -

Why did Phizer team with nanobot maker

Medical Issues & Conspiracies: 9 hours ago -

Pro Hamas protesters at Columbia claim hit with chemical spray

World War Three: 9 hours ago

top topics

-

Go Woke, Go Broke--Forbes Confirms Disney Has Lost Money On Star Wars

Movies: 14 hours ago, 13 flags -

Pro Hamas protesters at Columbia claim hit with chemical spray

World War Three: 9 hours ago, 11 flags -

Elites disapearing

Political Conspiracies: 12 hours ago, 9 flags -

Freddie Mercury

Paranormal Studies: 14 hours ago, 7 flags -

African "Newcomers" Tell NYC They Don't Like the Free Food or Shelter They've Been Given

Social Issues and Civil Unrest: 4 hours ago, 7 flags -

A Personal Cigar UFO/UAP Video footage I have held onto and will release it here and now.

Aliens and UFOs: 12 hours ago, 5 flags -

Two Serious Crimes Committed by President JOE BIDEN that are Easy to Impeach Him For.

US Political Madness: 7 hours ago, 5 flags -

Russian intelligence officer: explosions at defense factories in the USA and Wales may be sabotage

Weaponry: 3 hours ago, 4 flags -

911 emergency lines are DOWN across multiple states

Breaking Alternative News: 7 hours ago, 4 flags -

Former NYT Reporter Attacks Scientists For Misleading Him Over COVID Lab-Leak Theory

Education and Media: 9 hours ago, 4 flags

active topics

-

Elites disapearing

Political Conspiracies • 22 • : CitizenB -

I Guess Cloud Seeding Works

Fragile Earth • 22 • : Degradation33 -

Russian intelligence officer: explosions at defense factories in the USA and Wales may be sabotage

Weaponry • 43 • : FlyersFan -

African "Newcomers" Tell NYC They Don't Like the Free Food or Shelter They've Been Given

Social Issues and Civil Unrest • 6 • : Hecate666 -

Russia Flooding

Other Current Events • 3 • : theatreboy -

-@TH3WH17ERABB17- -Q- ---TIME TO SHOW THE WORLD--- -Part- --44--

Dissecting Disinformation • 520 • : cherokeetroy -

Former NYT Reporter Attacks Scientists For Misleading Him Over COVID Lab-Leak Theory

Education and Media • 3 • : Hakaiju -

Two Serious Crimes Committed by President JOE BIDEN that are Easy to Impeach Him For.

US Political Madness • 9 • : Myhandle -

MULTIPLE SKYMASTER MESSAGES GOING OUT

World War Three • 15 • : cherokeetroy -

A Personal Cigar UFO/UAP Video footage I have held onto and will release it here and now.

Aliens and UFOs • 10 • : Hakaiju

13