It looks like you're using an Ad Blocker.

Please white-list or disable AboveTopSecret.com in your ad-blocking tool.

Thank you.

Some features of ATS will be disabled while you continue to use an ad-blocker.

share:

Does anyone else remember experiences from childhood where you were wondering how to safely climb back down a tree? Feeling uneasy holding an awkward

position in a hiding place and wondering how you would get out when you needed to? Considering this as a child, I decided that it would be impossible

to get myself stuck, because if I could put myself into a position, I could just repeat the actions that got me there in reverse to free myself.

It turns out, that every known law of physics works the same whether you look at time going forwards or backwards. Toss a ball straight up into the air and catch it at the spot you threw it from. You'll need to exert the same force to catch it as you used to throw it. If you filmed it, it would be difficult, if not impossible to tell the difference between playing the video normally, and playing it in reverse.

But my confidence in my ability to navigate safely to and from tough spots was shaken by a fall. Not because I was hurt, but because I realized I couldn't spring back to my feet by doing a pushup. Ever do a cannonball or a belly-buster into a swimming-pool? You don't really have to move a muscle when you hit the water. But, if physics work the same whether you're looking at time running forwards or backwards, why can't you spring up from the pool back to the diving board (even the high-dive board) without moving a muscle? Why can you burn money into ashes, but not ashes into money?

Drop some food coloring into a glass of water to see the answer. The colored molecules drift randomly from the drop after they hit the water, until they spread evenly throughout the glass. They just keep moving around randomly and the odds of them happening to gather back into a single point all at once are exceedingly low. What would we see watching a cannonball dive, looking backwards through time? We'd see a kid floating in the pool, as random noises and little breezes start building up from all around the world snowballing as they go back to the pool; then little ripples of water would gather from the edges of the pool, gaining intensity as they synergyse around the kid. And, with a sudden burst of turbulence, waves splash as the kid bobs down and is launched up into the air onto the board! Theoretically, this is also possible looking forward through time; but the odds are negligibly low. So, the direction of time which becomes ordered is labeled the past, and the direction which becomes more random is labeled the future.

But what is randomness and where does it come from? Let's start with the word:

That's a start. So, those food coloring molecules aren't gathering to conspire, and none of the water molecules in the pool are trying to toss the kid onto the diving-board. That sounds about right. I imagine it would be quite difficult to launch the kid by agitating the water, you'd have a hard time landing them on that hi-dive board even if you were trying. We'll update our definition later, but if the basic members of the universe have no aim, where does order come from?

Some believe in a multiverse. That every possibility has a reality of its own. That not only did we have a big bang, but that there were infinitely many such events. Each universe can have its own laws of physics. So, some would obey Newtonian laws, others not. Some would have life, others not. Some would have gods, others not. etc... So our own universe has the Big Bang as the most ordered point in our timeline (while others have no real organization what so ever). And from that time, our universe just descends further into chaos. Time doesn't even run a straight line, it branches down every possible path from that root (flip a coin and half the branches land it on heads, while the other half land it on tails). So, we have literally everything happening with no reason; allowing order to arise from chaos as in the Greek myths. I'll explain later why I don't subscribe to this view, and present an alternative.

To be continued...

It turns out, that every known law of physics works the same whether you look at time going forwards or backwards. Toss a ball straight up into the air and catch it at the spot you threw it from. You'll need to exert the same force to catch it as you used to throw it. If you filmed it, it would be difficult, if not impossible to tell the difference between playing the video normally, and playing it in reverse.

But my confidence in my ability to navigate safely to and from tough spots was shaken by a fall. Not because I was hurt, but because I realized I couldn't spring back to my feet by doing a pushup. Ever do a cannonball or a belly-buster into a swimming-pool? You don't really have to move a muscle when you hit the water. But, if physics work the same whether you're looking at time running forwards or backwards, why can't you spring up from the pool back to the diving board (even the high-dive board) without moving a muscle? Why can you burn money into ashes, but not ashes into money?

Drop some food coloring into a glass of water to see the answer. The colored molecules drift randomly from the drop after they hit the water, until they spread evenly throughout the glass. They just keep moving around randomly and the odds of them happening to gather back into a single point all at once are exceedingly low. What would we see watching a cannonball dive, looking backwards through time? We'd see a kid floating in the pool, as random noises and little breezes start building up from all around the world snowballing as they go back to the pool; then little ripples of water would gather from the edges of the pool, gaining intensity as they synergyse around the kid. And, with a sudden burst of turbulence, waves splash as the kid bobs down and is launched up into the air onto the board! Theoretically, this is also possible looking forward through time; but the odds are negligibly low. So, the direction of time which becomes ordered is labeled the past, and the direction which becomes more random is labeled the future.

But what is randomness and where does it come from? Let's start with the word:

random (adj.) "having no definite aim or purpose," 1650s, from at random (1560s), "at great speed" (thus, "carelessly, haphazardly"), alteration of Middle English noun randon "impetuosity, speed" (c. 1300), from Old French randon "rush, disorder, force, impetuosity," from randir "to run fast," from Frankish *rant "a running" or some other Germanic source, from Proto-Germanic *randa (source also of Old High German rennen "to run," Old English rinnan "to flow, to run;" see run (v.)). etymonline.com

That's a start. So, those food coloring molecules aren't gathering to conspire, and none of the water molecules in the pool are trying to toss the kid onto the diving-board. That sounds about right. I imagine it would be quite difficult to launch the kid by agitating the water, you'd have a hard time landing them on that hi-dive board even if you were trying. We'll update our definition later, but if the basic members of the universe have no aim, where does order come from?

Some believe in a multiverse. That every possibility has a reality of its own. That not only did we have a big bang, but that there were infinitely many such events. Each universe can have its own laws of physics. So, some would obey Newtonian laws, others not. Some would have life, others not. Some would have gods, others not. etc... So our own universe has the Big Bang as the most ordered point in our timeline (while others have no real organization what so ever). And from that time, our universe just descends further into chaos. Time doesn't even run a straight line, it branches down every possible path from that root (flip a coin and half the branches land it on heads, while the other half land it on tails). So, we have literally everything happening with no reason; allowing order to arise from chaos as in the Greek myths. I'll explain later why I don't subscribe to this view, and present an alternative.

To be continued...

Time is a construct of man. There is no such thing. Man assigned values to divide the seasons and the day, but they have no real meaning. The time we

have created for convenience has no value other than comparative on other planets or in space.

Brings to mind this phrase.......Time flies like an arrow...

..

..

..

fruit flies like bananas.

Brings to mind this phrase.......Time flies like an arrow...

..

..

..

fruit flies like bananas.

Continued:

What should I expect to see based on the view mentioned at the end of the introduction? Maybe the Infinite Monkey Theorem can help put things into perspective. Let's see what happens when I close my eyes and bang some random keys off from my keyboard: 1-gvniedkmoj

So, I closed my eyes and hit some random keys to see what would happen. Would you believe the whole last paragraph was what came out from my experiment? Can you tell if I'm still doing it now? If randomness can lead to anything, is it possible to distinguish random from nonrandom? Would you be surprised to flip a coin and see it land on heads ten times in a row? There are 1,024 possible outcomes (not counting if the coin lands on its side), and ten heads in a row is just one of those 1,024 patterns like any other right? So, why should it surprise you?

Let's look a little more closely at coin tosses, they seem like a good conceptual model for randomness. Are all the patterns really equal? What is a pattern?

A repetition sounds like a good start. Denoting heads as 1 and tails as 0, the first toss allows 1 or 0. These seem equal to me. Two throws can leave: 00, 01, 10 or 11; half of these repeat (00 and 11). Three throws allow: 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110 or 111. All of these have a 1 or 0 showing up more than once, but only two of eight have the same digit every time. With four throws we see something special for the first time:

0000, 0001, 0010, 0011, 0100, 0101, 0110, 0111, 1000, 1001, 1010, 1011, 1100, 1101, 1110, 1111

Four of sixteen possible results yield patterns of patterns (0000, 0101, 1010, 1111)! Only two of sixteen results have the same pattern repeating every time (0000, 1111). The odds of flipping a fair coin n times and getting the same result all n times in a row are 2/(2^n). So random tosses are least likely to yield long runs of patterns. Is there any nonrandom process of generating 1s and 0s that we can compare this with?

To be continued...

What should I expect to see based on the view mentioned at the end of the introduction? Maybe the Infinite Monkey Theorem can help put things into perspective. Let's see what happens when I close my eyes and bang some random keys off from my keyboard: 1-gvniedkmoj

So, I closed my eyes and hit some random keys to see what would happen. Would you believe the whole last paragraph was what came out from my experiment? Can you tell if I'm still doing it now? If randomness can lead to anything, is it possible to distinguish random from nonrandom? Would you be surprised to flip a coin and see it land on heads ten times in a row? There are 1,024 possible outcomes (not counting if the coin lands on its side), and ten heads in a row is just one of those 1,024 patterns like any other right? So, why should it surprise you?

Let's look a little more closely at coin tosses, they seem like a good conceptual model for randomness. Are all the patterns really equal? What is a pattern?

Simple Definition of pattern

: a repeated form or design especially that is used to decorate something

: the regular and repeated way in which something happens or is done

: something that happens in a regular and repeated way merriam-webster.com

A repetition sounds like a good start. Denoting heads as 1 and tails as 0, the first toss allows 1 or 0. These seem equal to me. Two throws can leave: 00, 01, 10 or 11; half of these repeat (00 and 11). Three throws allow: 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110 or 111. All of these have a 1 or 0 showing up more than once, but only two of eight have the same digit every time. With four throws we see something special for the first time:

0000, 0001, 0010, 0011, 0100, 0101, 0110, 0111, 1000, 1001, 1010, 1011, 1100, 1101, 1110, 1111

Four of sixteen possible results yield patterns of patterns (0000, 0101, 1010, 1111)! Only two of sixteen results have the same pattern repeating every time (0000, 1111). The odds of flipping a fair coin n times and getting the same result all n times in a row are 2/(2^n). So random tosses are least likely to yield long runs of patterns. Is there any nonrandom process of generating 1s and 0s that we can compare this with?

To be continued...

a reply to: VP740

It's an interesting problem. We can use Monte Carlo analysis which tests random samples to find some underlying structure to the original data set. But aren't we really looking for a probability distribution? When you climbed up the tree, perhaps you thought that the best way down was to reverse the process. But was it? Did the variables change? What was the initial probability when you climbed up the tree versus the probability when you had to climb down the tree?

As a side interest (and profession), I write HFT algorithms for trading firms which seek to "front run" market activity (HFT = high frequency trading). Scientists can be a perfect fit for this type of job, believe it or not!! Here's the problem - for every algo you write, there's another one out there that will kill it. Why is that? Because it comes down to a probability distribution of the ever-changing variables. I think that's what you were faced with when you were up in the tree wanting to climb down. Some of the variables have changed - are those variables random? Probably not.

Anyway, randomness is something that is of great interest because when you add time and momentum to a process, it is extremely difficult to find pattern or structure. If you dig deep enough, maybe you find some nonrandom pattern or event. But here's the question: How long does it last? Here today and gone tomorrow!

I'm glad you started this topic - I'm always up to learn something new - sometimes I'm out of ideas!

It's an interesting problem. We can use Monte Carlo analysis which tests random samples to find some underlying structure to the original data set. But aren't we really looking for a probability distribution? When you climbed up the tree, perhaps you thought that the best way down was to reverse the process. But was it? Did the variables change? What was the initial probability when you climbed up the tree versus the probability when you had to climb down the tree?

As a side interest (and profession), I write HFT algorithms for trading firms which seek to "front run" market activity (HFT = high frequency trading). Scientists can be a perfect fit for this type of job, believe it or not!! Here's the problem - for every algo you write, there's another one out there that will kill it. Why is that? Because it comes down to a probability distribution of the ever-changing variables. I think that's what you were faced with when you were up in the tree wanting to climb down. Some of the variables have changed - are those variables random? Probably not.

Anyway, randomness is something that is of great interest because when you add time and momentum to a process, it is extremely difficult to find pattern or structure. If you dig deep enough, maybe you find some nonrandom pattern or event. But here's the question: How long does it last? Here today and gone tomorrow!

I'm glad you started this topic - I'm always up to learn something new - sometimes I'm out of ideas!

edit on 18-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: Phantom423

Well, going up the tree, I usually wouldn't break branches or cause significant changes to the situation; and of course I wouldn't expect to reverse my path if I had. Let's say your driving, and every road you go on is two-way. No matter how many turns you take, you can always retrace your path. The Rubik's Cube is another great example of a reversible process. If you didn't keep track of your moves, it might be tricky reversing your steps, but it's always possible. Chess has a mixture of reversible (ignoring the 50 moves without progress rule), and irreversible moves (pawn pushes, captures, castling etc...).

What confused me about falling was, I didn't notice the variables I affected. Let's say I walk onto a ledge and it breaks. As a kid I saw that as irreversible because I changed the landscape. But when I just tripped on a root and fell, I didn't notice that I'd caused changes outside myself. The root wasn't broken, the ground wasn't cratered, the only thing that I saw in a different position was myself. In a situation were the only changes I made were to myself, I expected to be able to do movements to put myself back as I was (like moving a knight or a rook back where it came from). What I failed to realize was that I transferred kinetic energy in the form of sounds and heat to materials outside myself.

At first I was going to write about an experiment I did as a kid to test my ability to control my reflexes and get a better understanding of what happens when I fall. I gathered all the stuffed animals, blankets and cushions I could find. Then I jumped off the top of my bunk bed landing in the pile of cushions on my side (fortunately, I incurred no injury in the process). I decided a cannonball into a pool would provide a better illustration of what happens though (it was hard for me to figure out what was going on when the effects of my actions were less visible).

I'm working on getting my next section up with a minimum of math. The sentences come out fairly ugly. Take this as an example: Using a fair coin and our simple definition of pattern as our example; the probability p of seeing a sequence of length l repeating r times and filling the total output of n coin tosses, and n being equal to l*r tosses, it comes to: p=2^(l-n). Can you follow that OK, or does it only make sense to me because I already know what I'm trying to say? And the equations are inconvenient to display on ATS if I use things like sigma notation. I still want to put up some basic equations separately as a bonus for those who want more detail though. While I can test for some traits of randomness in C++, I'm struggling to come up with formulas that would be easy for the average person to follow, but still be worth looking at. We'll see how things work out.

Well, going up the tree, I usually wouldn't break branches or cause significant changes to the situation; and of course I wouldn't expect to reverse my path if I had. Let's say your driving, and every road you go on is two-way. No matter how many turns you take, you can always retrace your path. The Rubik's Cube is another great example of a reversible process. If you didn't keep track of your moves, it might be tricky reversing your steps, but it's always possible. Chess has a mixture of reversible (ignoring the 50 moves without progress rule), and irreversible moves (pawn pushes, captures, castling etc...).

What confused me about falling was, I didn't notice the variables I affected. Let's say I walk onto a ledge and it breaks. As a kid I saw that as irreversible because I changed the landscape. But when I just tripped on a root and fell, I didn't notice that I'd caused changes outside myself. The root wasn't broken, the ground wasn't cratered, the only thing that I saw in a different position was myself. In a situation were the only changes I made were to myself, I expected to be able to do movements to put myself back as I was (like moving a knight or a rook back where it came from). What I failed to realize was that I transferred kinetic energy in the form of sounds and heat to materials outside myself.

At first I was going to write about an experiment I did as a kid to test my ability to control my reflexes and get a better understanding of what happens when I fall. I gathered all the stuffed animals, blankets and cushions I could find. Then I jumped off the top of my bunk bed landing in the pile of cushions on my side (fortunately, I incurred no injury in the process). I decided a cannonball into a pool would provide a better illustration of what happens though (it was hard for me to figure out what was going on when the effects of my actions were less visible).

I'm working on getting my next section up with a minimum of math. The sentences come out fairly ugly. Take this as an example: Using a fair coin and our simple definition of pattern as our example; the probability p of seeing a sequence of length l repeating r times and filling the total output of n coin tosses, and n being equal to l*r tosses, it comes to: p=2^(l-n). Can you follow that OK, or does it only make sense to me because I already know what I'm trying to say? And the equations are inconvenient to display on ATS if I use things like sigma notation. I still want to put up some basic equations separately as a bonus for those who want more detail though. While I can test for some traits of randomness in C++, I'm struggling to come up with formulas that would be easy for the average person to follow, but still be worth looking at. We'll see how things work out.

edit on 18-9-2016 by VP740 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: VP740

I think you might take into consideration the influence of gravity - I think that would be the starting point - 9.8 m/s/s

So when you fell out of bed or fell out of the tree you would have to consider all the variables that influence gravity - not what influenced you (although it really could be considered the same, I guess).

The variables might be random to the extent that wind, temperature, flying objects - whatever, could influence the rate of your fall. But overall, it's still the rate of free fall and acceleration that governs that fall.

Also remember that our universe is an open system - if we lived in an adiabatic system, then the rules would always apply perfectly. But they don't because anything can influence the outcome. We would have to include entropy in the mix.

What confused me about falling was, I didn't notice the variables I affected.

What I failed to realize was that I transferred kinetic energy in the form of sounds and heat to materials outside myself.

I think you might take into consideration the influence of gravity - I think that would be the starting point - 9.8 m/s/s

So when you fell out of bed or fell out of the tree you would have to consider all the variables that influence gravity - not what influenced you (although it really could be considered the same, I guess).

The variables might be random to the extent that wind, temperature, flying objects - whatever, could influence the rate of your fall. But overall, it's still the rate of free fall and acceleration that governs that fall.

Also remember that our universe is an open system - if we lived in an adiabatic system, then the rules would always apply perfectly. But they don't because anything can influence the outcome. We would have to include entropy in the mix.

edit on 18-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

edit on 18-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason

given)

edit on 18-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: Phantom423

Well, the way I look at it is this: Let's say my legs are strong enough to let me jump two feet off the ground. I can do that fairly reliably. Yes, I'll need to consume energy from oxygen and food if I want to keep doing it, but my range comes out to being fairly consistent (until the effects of old age come into play). If I jump down further than I could jump up, I'll exert an impact on landing greater than I could exert just by jumping from the spot I landed (because of velocity I picked up from gravity during free fall). Even if I can endure this impact without sustaining injury, I can't reproduce the force I need to get back to were I came from.

Well, the way I look at it is this: Let's say my legs are strong enough to let me jump two feet off the ground. I can do that fairly reliably. Yes, I'll need to consume energy from oxygen and food if I want to keep doing it, but my range comes out to being fairly consistent (until the effects of old age come into play). If I jump down further than I could jump up, I'll exert an impact on landing greater than I could exert just by jumping from the spot I landed (because of velocity I picked up from gravity during free fall). Even if I can endure this impact without sustaining injury, I can't reproduce the force I need to get back to were I came from.

edit on 18-9-2016 by VP740 because: (no reason given)

edit on

18-9-2016 by VP740 because: (no reason given)

edit on 18-9-2016 by VP740 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: Phantom423

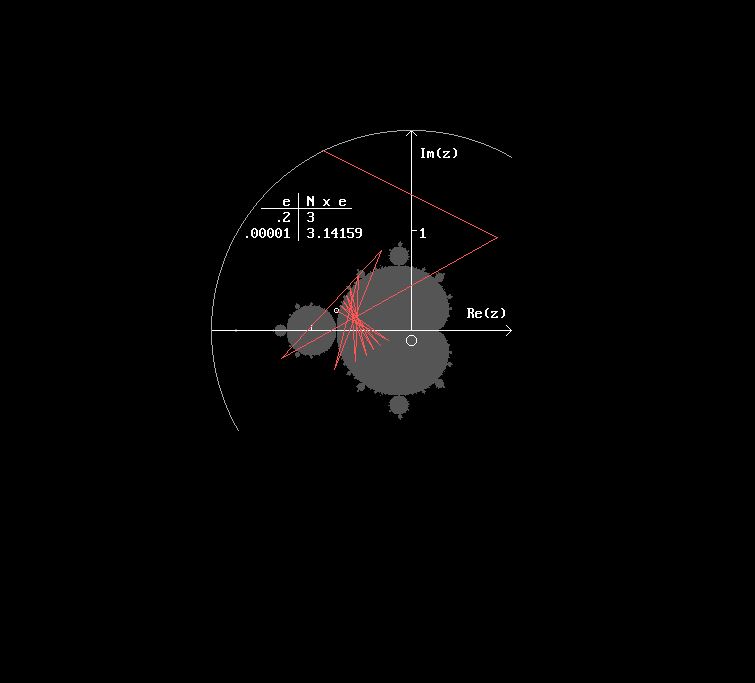

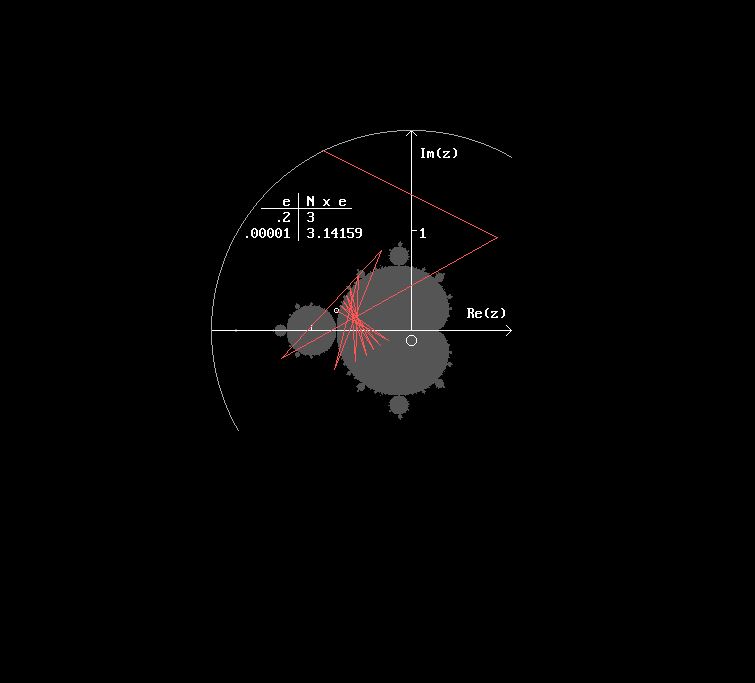

I guess he should have said his approximation of Pi at that point was exact to four decimal places.

I guess he should have said his approximation of Pi at that point was exact to four decimal places.

xizd1:

These are two correct statements of truth. Time as we understand it does not exist at all. It has no existential reality of its own. We don't perceive time, we perceive changes, and every change, no matter how big or small has a duration length, and it is the changes in durations we perceive, that gives us our sense of time.

Time is a construct of man. There is no such thing [as time].

These are two correct statements of truth. Time as we understand it does not exist at all. It has no existential reality of its own. We don't perceive time, we perceive changes, and every change, no matter how big or small has a duration length, and it is the changes in durations we perceive, that gives us our sense of time.

This might be of interest to you. Some of what is in the OP aligns with the 2nd law thermodynamics/arrow of time, entropy and multiverse idea.

When I saw the title it made me think of this and a few others.

Get past the first 6minutes or so.

When I saw the title it made me think of this and a few others.

Get past the first 6minutes or so.

a reply to: roadgravel

Leonard Susskind is the best - I've taken several of his online courses. If you don't have a background in QM, start with this:

theoreticalminimum.com...

Well worth the effort to get a foothold in the mathematics and physics.

Leonard Susskind is the best - I've taken several of his online courses. If you don't have a background in QM, start with this:

theoreticalminimum.com...

A number of years ago I became aware of the large number of physics enthusiasts out there who have no venue to learn modern physics and cosmology. Fat advanced textbooks are not suitable to people who have no teacher to ask questions of, and the popular literature does not go deeply enough to satisfy these curious people. So I started a series of courses on modern physics at Stanford University where I am a professor of physics. The courses are specifically aimed at people who know, or once knew, a bit of algebra and calculus, but are more or less beginners.

Well worth the effort to get a foothold in the mathematics and physics.

a reply to: elysiumfire

Perhaps time and change are one in the same? Is it possible to have change i.e. go from A to B and not have a time interval?

In QM superposition allows for particles to be in two places at once, so maybe in the Q world time is irrelevant - but in our physical world, it is relevant. I don't think we can say that time doesn't exist without us - there's no way to prove that. If time is only a function of human existence then we would have to assume that the universe as we know it today was actually created by us - because time is a key element in its creation and development - change = time and vice versa. No time, no universe. IMO of course - no citations on this one!

Perhaps time and change are one in the same? Is it possible to have change i.e. go from A to B and not have a time interval?

In QM superposition allows for particles to be in two places at once, so maybe in the Q world time is irrelevant - but in our physical world, it is relevant. I don't think we can say that time doesn't exist without us - there's no way to prove that. If time is only a function of human existence then we would have to assume that the universe as we know it today was actually created by us - because time is a key element in its creation and development - change = time and vice versa. No time, no universe. IMO of course - no citations on this one!

edit on 19-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: VP740

He did say that, I think??

I was thinking fractals of Pi and came across this website: www.pi314.net...

Some interesting reading there including a discussion of fractals.

He did say that, I think??

I was thinking fractals of Pi and came across this website: www.pi314.net...

Some interesting reading there including a discussion of fractals.

edit on 19-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

edit on 19-9-2016 by Phantom423 because: (no reason given)

a reply to: roadgravel

Thanks! I'll probably have to go over this a few times before concluding the main part of this thread.

Thanks! I'll probably have to go over this a few times before concluding the main part of this thread.

a reply to: Phantom423

Ever notice our entire number system is a fractal?

0000000

0000001

0000010

0000011

0000100

0000101

0000110

0000111

0001000

0001001

0001010

0001011

0001100

0001101

0001110

0001111

0010000

...

Speaking fractals, trying to find some formulas to explain some basic algorithms for analyzing randomness, I discovered Phi working behind the scenes (φ, that wasn't a typo). I'll show you what I come up with later.

Ever notice our entire number system is a fractal?

0000000

0000001

0000010

0000011

0000100

0000101

0000110

0000111

0001000

0001001

0001010

0001011

0001100

0001101

0001110

0001111

0010000

...

Speaking fractals, trying to find some formulas to explain some basic algorithms for analyzing randomness, I discovered Phi working behind the scenes (φ, that wasn't a typo). I'll show you what I come up with later.

Phantom423:

You have a want to insist that time does actually exist. So, for your edification here's the simplest way of defining 'time'. Time is our quale perception of change of duration. In other words, time is the expression we use to denote our qualitative experience of duration. It is simply a by-product of sensing. Equally, in mathematics, time is just an abstract measuring of speed times (spatial) distance, or the inverse of that.

Where do we get our sense of 'space' from? Suppose there was no content in space, would you still be able to perceive space, or be able to enjoy the perception of spatiality? The answer is no, you would not. Content in space is what allows us to appreciate space and spatiality. Content vectorises space. You know there is space by the measurable vector coordinates between content in space. Without content, how would you measure space, and in association with that, how could you possibly measure time? Without content in space, you would not have any events, and would not be able to pin your first vector coordinate on to anything.

Don't get me wrong, time does exist, but only in the abstract, as a useful number of units of measurement. However, time itself is not measured, we only measure (or sense as stimuli) durations of events for our qualitative experience of time.

Perhaps time and change are one in the same? Is it possible to have change i.e. go from A to B and not have a time interval?

In QM superposition allows for particles to be in two places at once, so maybe in the Q world time is irrelevant - but in our physical world, it is relevant. I don't think we can say that time doesn't exist without us - there's no way to prove that. If time is only a function of human existence then we would have to assume that the universe as we know it today was actually created by us - because time is a key element in its creation and development - change = time and vice versa. No time, no universe. IMO of course - no citations on this one!

You have a want to insist that time does actually exist. So, for your edification here's the simplest way of defining 'time'. Time is our quale perception of change of duration. In other words, time is the expression we use to denote our qualitative experience of duration. It is simply a by-product of sensing. Equally, in mathematics, time is just an abstract measuring of speed times (spatial) distance, or the inverse of that.

Where do we get our sense of 'space' from? Suppose there was no content in space, would you still be able to perceive space, or be able to enjoy the perception of spatiality? The answer is no, you would not. Content in space is what allows us to appreciate space and spatiality. Content vectorises space. You know there is space by the measurable vector coordinates between content in space. Without content, how would you measure space, and in association with that, how could you possibly measure time? Without content in space, you would not have any events, and would not be able to pin your first vector coordinate on to anything.

Don't get me wrong, time does exist, but only in the abstract, as a useful number of units of measurement. However, time itself is not measured, we only measure (or sense as stimuli) durations of events for our qualitative experience of time.

new topics

-

Remember These Attacks When President Trump 2.0 Vengeance-Retribution Commences.

2024 Elections: 15 minutes ago -

Predicting The Future: The Satanic Temple v. Florida

Conspiracies in Religions: 23 minutes ago -

WF Killer Patents & Secret Science Vol. 1 | Free Energy & Anti-Gravity Cover-Ups

General Conspiracies: 2 hours ago -

Hurt my hip; should I go see a Doctor

General Chit Chat: 3 hours ago -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues: 4 hours ago -

Michigan school district cancels lesson on gender identity and pronouns after backlash

Education and Media: 4 hours ago -

When an Angel gets his or her wings

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 5 hours ago -

Comparing the theology of Paul and Hebrews

Religion, Faith, And Theology: 6 hours ago -

Pentagon acknowledges secret UFO project, the Kona Blue program | Vargas Reports

Aliens and UFOs: 7 hours ago -

Boston Dynamics say Farewell to Atlas

Science & Technology: 7 hours ago

top topics

-

The Democrats Take Control the House - Look what happened while you were sleeping

US Political Madness: 10 hours ago, 18 flags -

In an Historic First, In N Out Burger Permanently Closes a Location

Mainstream News: 12 hours ago, 16 flags -

A man of the people

Medical Issues & Conspiracies: 17 hours ago, 11 flags -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News: 9 hours ago, 9 flags -

Biden says little kids flip him the bird all the time.

Politicians & People: 9 hours ago, 9 flags -

Michigan school district cancels lesson on gender identity and pronouns after backlash

Education and Media: 4 hours ago, 7 flags -

Pentagon acknowledges secret UFO project, the Kona Blue program | Vargas Reports

Aliens and UFOs: 7 hours ago, 6 flags -

WF Killer Patents & Secret Science Vol. 1 | Free Energy & Anti-Gravity Cover-Ups

General Conspiracies: 2 hours ago, 6 flags -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues: 4 hours ago, 5 flags -

Boston Dynamics say Farewell to Atlas

Science & Technology: 7 hours ago, 4 flags

active topics

-

Remember These Attacks When President Trump 2.0 Vengeance-Retribution Commences.

2024 Elections • 3 • : KrustyKrab -

Michigan school district cancels lesson on gender identity and pronouns after backlash

Education and Media • 9 • : TheMisguidedAngel -

Predicting The Future: The Satanic Temple v. Florida

Conspiracies in Religions • 3 • : Vermilion -

Mood Music Part VI

Music • 3064 • : MRTrismegistus -

Man sets himself on fire outside Donald Trump trial

Mainstream News • 41 • : TheMisguidedAngel -

The New, New ATS Members Photos thread. Part 3.

Members • 1653 • : zosimov -

A man of the people

Medical Issues & Conspiracies • 15 • : PrivateAngel -

Israel attacking Iran again.

Middle East Issues • 27 • : KrustyKrab -

I hate dreaming

Rant • 7 • : TheMichiganSwampBuck -

MULTIPLE SKYMASTER MESSAGES GOING OUT

World War Three • 53 • : Zaphod58